Dear Editor,

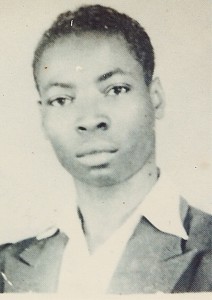

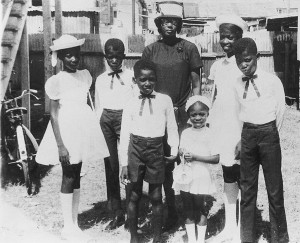

January 2 marked the 40th anniversary of the death of my father William Norton, along with four other policemen and two civilians who were murdered during the Rupununi Uprising in 1969. This letter is my personal tribute to all the victims of this yet unpunished crime, especially my mother, Eileen Norton, who has borne this tragedy with considerable dignity. It is also my personal indictment of the criminal justice system in Guyana at the time, which in my opinion, failed to render justice to the victims.

I was three years old at the time of the Rupununi Uprising, the youngest of six children, and over the years, I have read quite a bit concerning the Uprising. In recent months additional information has come to light, some from witnesses, some from political activists with their own political agenda, others from newspaper articles, whose authors have in some instances displayed a shocking lack of sensitivity or even awareness that their articles could be read by the victims of this horrible crime.

In her article, published in the October 12, 2008 edition of Stabroek News, entitled ‘Terror on Thursday,’ Miranda La Rose interviews Steve Sagar, a witness to the Rupununi Uprising. (see article at http://www. stabroeknews.com/news/terror-on-thursday/)

He describes in chilling detail the events of this day. While I applaud Mr Sagar for coming forward, one question remains: would his testimony have made a difference to the outcome of the trial at the time? Or would it have made absolutely no difference in what appears to me to have been a rush to judgement, and a desire to appease in the words of one judge, “the watching world.”

Whatever the answer, seven of those charged with murder were acquitted; the judge ordered that three others be retried for murder, but charges were later dropped by the Director of Public Prosecutions.

This leads me to my second question: why were the charges dropped, and at whose request?

The victims? I think not. The judicial system has declared in essence that no one is responsible for the murder of their husbands, fathers, brothers…

My third question is as follows: Was there ever an attempt to extradite the members of the Hart and Melville families, namely Valerie Hart, Dick Hart and Neville Junor and their associates from their hideouts in Venezuela and Brazil? If yes, when, and if no, why not?

A few years ago I stumbled on a picture of the Hart-Melville family reunion in the Rupununi.

(see http://community.iexplore.com/ planning/journalEntryActivity.asp?JournalID=6268&ReviewID=1157471&n=Mashramani&t=Rollerblading) The author, Tropic, described the 2001 reunion or Mashramani as follows:

“A Mashramani is a family get together and a major importance to social activities in the Rupununi savannah. Depending upon the family … they gather to undertake a particular job or celebrate an elder’s birthday or just a good reason to have a good feast and meet new family. We managed to get a Mashramani done at takubin for the Gorinsky/Ware/Melville/Hart family and this was the first time in over 30 years that some of this family met under one roof and in harmony.”

I find it absolutely amazing that these fugitives from justice were able to come back to Guyana openly with impunity. And why shouldn’t they? All charges were dropped against them, which leads me to my fourth question:

Is there a statute of limitations on murder?

Cecilia McAlmont in her March 24, 2005 Stabroek News article, ‘Guyanese women in politics/power and decision making: Valerie Hart and the Rupununi Uprising,’ seems to express somewhat reluctant, yet clear admiration for Valerie Hart’s role in the Rupununi Uprising, referring to her as a, “Rebel Envoy,” “shrewd political strategist,” “aggressive and shrewd lobbyist,” a woman of “tremendous courage and determination.”

Well, neither I or my family would describe Valerie Hart in such glowing terms. To us she is simply one of my father’s murderers who was never brought to justice.

Some might be tempted to ask if the victims ever received any compensation for their loss. All I can remember ever receiving was 500 Guyana dollars on my 18th birthday. I left Guyana a few months later. After all these years all I am looking for is answers to unanswered questions. I would like to conclude by asking my fifth and final question, which is a quote from Ms McAlmont’s 2005 article:

“If the now almost seventy-one-year-old Valerie Hart were to come out of exile from Brazil where she is reported to be living and return to the country of her birth, how would she be viewed by the different stakeholders? Given the unequivocal condemnation of the rebellion by the then main opposition party now the government in power (although they had asserted that the government almost brought it on themselves because of their disregard for Amerindian concerns), would she be hauled before the court for treason or participating in the uprising, or granted a pardon… or will she be quietly ignored?”

Hopefully, after forty years, we the victims may finally have some answers to these questions.

Yours faithfully,

Thula Norton-Lambert