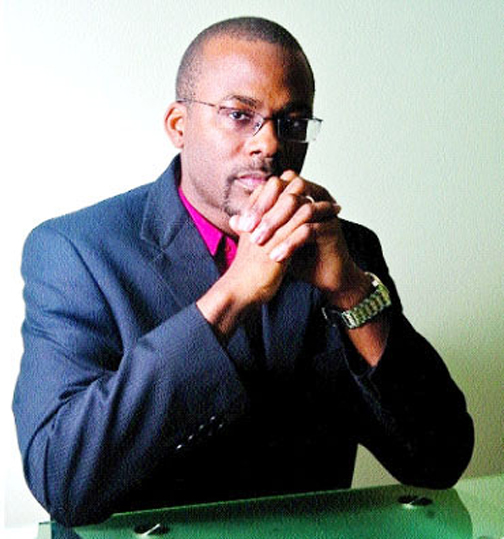

Gerard Best goes one on one with Bevil Wooding, the Caribbean’s very own technology ambassador

Since news broke in the international media that a Trinidad and Tobago technology evangelist was one of only seven persons in the world trusted with keys for the Internet, the spotlight has turned to this tiny Caribbean state and to Bevil Wooding, the man with a key to the Internet. Wooding is the Chief Knowledge Officer at Congress WBN, a Trinidad-based NGO with operations in over 95 countries. He was selected by ICANN (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) from among 60 candidates to serve as the “trusted community representative” from Latin America and the Caribbean. ICANN is the organization responsible for managing the systems that store, translate and retrieve the numerical address equivalents of familiar web addresses we use every day, such as google.com, uwi.edu or wikipedia.org.

What exactly is this key to the Internet?

I am one of seven people, designated Recovery Key Share Holders, entrusted with a special cryptographic ‘smart-card’ that holds part of a key used to generate the “Domain Name Server Security Extensions” (DNSSEC) protocol that protects domain names on the Internet. In the event of a natural disaster or major Internet security breach, we could be called upon to fly to a secure location in the United States where at least five of these encrypted key fragments must be combined as part of a process to restore the security of the Internet’s domain name system (DNS). You can think of it as ICANN’s disaster-preparedness plan for the Internet.

The keys don’t actually restart the Internet. In fact, the Internet will not shut down or collapse, even if the DNSSEC system failed, contrary to some reports in the international media. DNSSEC sits on top of ‘the Internet’ as an additional security layer for end users to validate DNS data and to confirm they have a connection to a legitimate operator and not a spoof. If DNSSEC were to fail, the underlying Internet communication medium will continue to function as normal.

How were you actually chosen? Was it by election, or were you “appointed”?

As part of a joint effort to secure the DNS, ICANN made a call for volunteers to act as trusted representatives of the Internet community. The selection process was based on Statements of Interest, solicited from the Internet community and published online. ICANN then selected 21 persons to be Trusted Community Representatives (TCRs) from among 60 candidates from around the world. I applied and was selected to serve as one of seven Recovery Key Share Holders. As a TCR, I am effectively representing Latin America and Caribbean.

For years we have been hearing that Latin America and the Caribbean must make the transition to knowledge-based economies if they are to have any chance of sustainable development. Are Caribbean governments and business making the best use of technology?

The short answer is ‘they are trying’. However, realizing the true potential of Information and Communications Technology (ICT) is still hampered by a number of factors. One can ask, is there a coherent regional approach to ICT strategic planning? Is our education system providing the human resource pool to supply Caribbean business with the right mix on competence and correct perspective needed to innovate, adapt and thrive? Are our regional institutions effective or even relevant to the current landscape?

In practical terms, what are some of the obstacles preventing Caribbean governments and business from making the best use of technology?

Accelerating the spread of the Internet, encouraging development of Internet-based economic activity and reaping consequent social benefit in the Caribbean is dependent on reducing Internet connectivity and bandwidth costs and improving quality of service. Realizing the true potential of Information and Communications technology is still hampered by a number of factors including: the lack of political will to prioritise adoption of ICTs as a viable and sustainable alternative to traditional economic pillars such as agriculture and tourism; the inadequacy of support systems for incubating and facilitating technology innovators and entrepreneurs; insufficient public awareness and limited advocacy group pressure on service providers and policy makers; and limited representation at international fora where decisions are taken that have implications at the national and regional level.

Counteracting these forces requires that in addition to Governments, the private sector, academia and civil society groups must be actively engaged. I am hopeful that new administrations across the region can help facilitate new approaches to national and regional development. However, the main responsibility for political re-prioritization lies with Caribbean societies. As a collective whole, we must all push for the adoption of innovation through ICTs as a viable and sustainable alternative to traditional economic pillars such as agriculture and tourism. These are just some of the issues; there are many more.

Reprinted from the Trinidad and Tobago Review