Part 1

By Jamellah Bayley

This article is the first in a two-part series that examines the health conditions in British Guiana during the 1890s. Part one gives a brief overview of the general conditions in the colony including economic and living conditions as both had implications for the health of residents.

At the time of British acquisition, the institution of African Slavery was still in force. The ethnic composition of the territory included Africans, Europeans, Indigenous peoples and mixed groups that were the results of miscegenation among groups.

The Europeans had brought with them various diseases that had been responsible for the decimation of the Amerindians. By the 1890s (the period of focus of this paper) the composition of the society had changed as had its economic situation. Slavery was over, indentured servants had been introduced and the sugar industry was facing many difficulties.

The general conditions of the colony were despicable. As the West India Royal Commission of 1897 noted “there is evidence of much poverty in the colony especially in the capital, among skilled artisans and mechanics as well as among persons above the laboring class ….”

The issue of health is not an isolated one. Many factors interact to determine the health conditions of a society. Factors such as employment levels, this directly determined how much persons can afford health care. Additionally living conditions will affect the spread of certain contagious diseases.

Economic Conditions

After emancipation, a number of ex-slaves left the plantations to establish their own villages. Their goal was independence from plantation life. However, the euphoria soon wore off and many of them were forced to seek plantation work to subsidise their income. The planters meanwhile had imported immigrants to work on the plantations and by the 1890s the vast majority of plantation workers were East Indian.

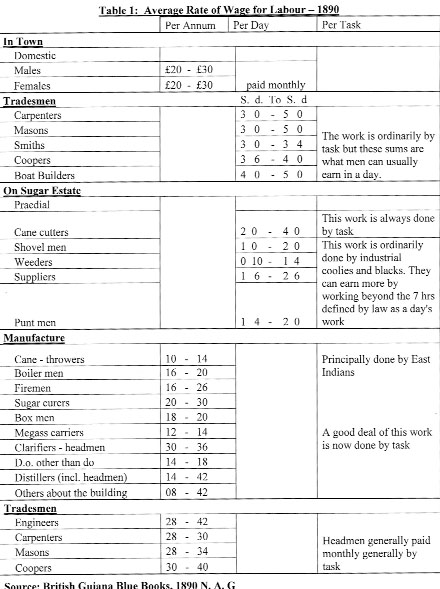

In the 1890s the sugar industry was in a crisis. The depression in the sugar industry was due to a fall in prices of sugar and its by-products. This resulted in the amalgamation of some estates and abandonment of others. The failure in the sugar industry meant great want of employment and reduction in the already low wages for labourers, carpenters, engineers and other artisans.

Low wages were constant throughout the decade. (See Tables 1 & 2) These meagre compensations were insufficient to adequately cover all their basic expenses of accommodation, clothing and food let alone health care.

Living Conditions

Throughout the decade under consideration, the death rate in the colony exceeded the birth rate. In 1890 the death rate exceeded birth rate by 3,275, in 1893 by 2,417, by 1895/96 it was by 168 and by 1898/99 it was by 1206.

By 1898/99 there were no epidemics but mortality was high as 34 per thousand. This was attributed to the unsanitary conditions under which they lived.

After emancipation many Africans settled in villages on the coast. They erected cottages. These cottages were nothing more than roughly constructed huts made of decaying palms with small rooms. There were more often than not overcrowded and badly ventilated. The villages had inadequate drainage facilities, so there were subjected to constant flooding. This consequently led to water logging. This in turn resulted in water-borne illnesses and was breeding grounds for pests like mosquitoes.

On the estates the indentured servants lived in the same dilapidated structures formerly occupied by the now ex-slaves. It was not until 1892 that new ranges were constructed on twenty-eight estates. Indian immigrants were reported to have plastered the earthen floor of their dwelling with cow dung.

Water supply consisted of polluted, foul stagnant water from trenches and ponds. Initially there were no latrines or conservancy of any sort. It meant that the grounds that surrounded their water supply were used as latrines. Not only was the water contaminated by human excrement but by cattle’s as well, as these were allowed to graze on these grounds.

The second part in this series will focus on the health conditions in British Guiana.