Adele Perry is Associate Professor of History and Canada Research Chair in Western Canadian Social History at the University of Manitoba. She is working on a book that uses the families of James Douglas and Amelia Connolly to discuss the lived history of the nineteenth-century British empire.

By Adele Perry

James Douglas was born in the colony of Demerara in 1803, the year that it again became a British possession after a stretch of intermittent Dutch, British and French rule. Douglas died in 1877 in Victoria, the small capital city of what was by then Canada’s west coast province of British Columbia.

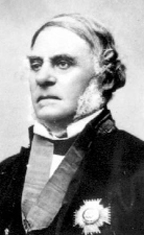

Douglas had been a powerful man in the fur-trade, and then governor of the British colonies of Vancouver Island and then British Columbia from 1851 until he fully retired in 1864. By the time of his death, Douglas was a wealthy and influential man, and the day of his funeral was declared a civic holiday. People lined the streets of Victoria to pay their respects to a man who was widely acknowledged as a local hero.

Douglas’s Guyanese origins were rarely mentioned in the tributes that were written in honour of his passing. Many of the historians who wrote biographies of Douglas in the middle years of the twentieth-century replicated this silence. They glossed over or altogether denied Douglas’s birth and childhood in Demerara, instead focusing on his Scots lineage and portraying him as a self-made man and a frontier hero in the North American tradition.

The 150th anniversary of the founding of British Columbia as a colony was celebrated in 2008, and it was only then that Douglas’s Guyanese heritage took on a meaningful role in public discussion. Identical statues of Douglas were erected in Mahaica, the likely home of his paternal family’s sugar estate, and in Fort Langley, British Columbia, where Douglas first proclaimed British Columbia to be under Britain’s control.

There is much more to be said about James Douglas and his family and their lives in Great Britain, the colonies that later became Guyana and those that later became Canada. This column usually focuses on the many meanings of diaspora for present-day Guyanese at home and abroad, but this article will focus on some of these transnational ties in a very different historical era, when they were experienced differently and meant different things for the individuals involved and the societies they lived in.

We don’t know very much about James Douglas’s early years or his family of origin. Nor are we ever likely to. Early nineteenth-century colonial governments did not usually keep records of births and deaths, and like many children born to colonial contexts, Douglas was of mixed origins and would have been considered ‘illegitimate’ by contemporary elite British standards.

What we know of his family of birth and early life comes from scattered references in Douglas private records kept in the British Columbia Archives, the occasional remarks of his family and friends, and most of all the painstaking research of a Canadian historian named Charlotte Girard, who combed the available records in the late 1970s. Girard concluded that Douglas’s mother was a free woman of colour named Martha Ann Ritchie, later Telfer, and his father a Scottish man named John Douglas.

I have not been able to replicate all of Girard’s research. As Guyanese historians know well, the past three decades have not been kind to Guyana’s archives, and archival material that was available in the 1970s is not always available now.

But the records at the Walter Rodney Archives on Homestretch Avenue and in the National Archives in Britain do confirm some of Girard’s findings and help to flesh out the story of Douglas’ mother and grandmother, Rebecca Ritchie. Their family seems to have been fairly typical of early nineteenth-century Creole elites, empowered by their freedom in a society organized around slavery but disempowered by their race and location in a hierarchical colonial world. By 1817, Telfer owned more than thirty slaves. Ritchie owned even greater numbers of slaves in both Demerara and Barbados, and used the courts in Demerara to protect her interests. Douglas’s father’s family was typical of another component of early nineteenth-century Guyanese life: itinerant Scots tied to the brutal economies of sugar production and trade.

John Douglas’ family had longstanding ties to Demerara and Berbice, and more particularly to sugar plantations and shipping interests there.

Whatever the character of his relationship with Telfer, it was likely never celebrated in a church or committed to a government register. But they had three children – Alexander and James, born in the early years of the nineteenth-century, and a daughter, Rebecca, born in 1812. John Douglas returned permanently to Scotland in the 1810s, where he had another family, one recognized by British law and custom.

For free boys of colour in the early nineteenth-century, formal education in Europe could provide them with critical access to the privileges usually accorded only to whites. When James and Alexander Douglas were around eight and ten years old they were sent to school in Lanark, Scotland. There the boys boarded with a local family and were given the kind of general education that made Scottish men so useful to the practical administration of the British Empire. In 1819, when the boys were teenagers, they were apprenticed to the North West Company, the fur-trade enterprise located in Montreal.

Historians have not paid serious attention to the connections between the sugar colonies of the nineteenth-century Caribbean and the colonization of western North America. But recent research on families like the Douglas’s and on biographies that spanned Barbados and western Canada by my colleague Ryan Eyford suggests that the Douglas’s were not only men from the Caribbean’s free Black and middling white communities who opted to move to other colonial contexts in the wake of the rearrangement of the sugar trade after the abolition of the slave trade in 1807 and the abolition of slavery in the British empire in 1833.

Alexander Douglas would spend only a few years in the fur-trade, but James would spend his adult life in fur-trade territories and the settler societies that emerged out of them. Douglas worked first for the North West Company and later for the Hudson’s Bay Company.

He began as a clerk and concluded his career as the dominant company official on the west coast of North America, serving as Chief Trader at Fort Vancouver, in what is now Oregon, USA, and Chief Factor at Fort Victoria.

Douglas married into the North American fur-trade as well. In 1827, Douglas made a customary marriage with Amelia Connolly, the teenage daughter of his direct superior and a Cree Indigenous woman. A decade later Connolly and Douglas would be remarried by an Anglican missionary. In the middle years of the nineteenth-century, many elite men in the fur-trade married white women and put their Indigenous ones aside, but Douglas and Connolly’s marriage weathered enormous social transitions in western North America. She bore thirteen children, and they raised six – five daughters and one son – to adulthood.

In 1851 the British colonial office appointed Douglas governor of the new colony of Vancouver Island. With his Creole background and history in the fur-trade rather than the colonial service, Douglas was an unconventional choice for Governor, but he was the one that Britain made when the colony’s first governor left the post in frustration. In 1858 Douglas became governor of the adjacent new colony of British Columbia as well.

As Governor, Douglas was critical to the early years of the colony, and to its particular history of ignoring or denying Indigenous peoples’ claims to the land. Douglas remained in this double post until he retired in 1863-4, and was named a Knight Commander of the Order of the Bath. In retirement the man now known as Sir James devoted himself to his beloved family, old friends, and tending to his considerable fortune, much of it tied to land purchased around the city of Victoria.

Douglas’s adult life was profoundly rooted in British Columbia, which became a Canadian province in 1871. Douglas spoke rarely about his early life or family, and maintained a distant public persona that discouraged questions about his own history and racial identity. His considerable wealth and prestige made this possible. Within the local context of British Columbia, that Douglas’s wife was Indigenous was a bigger and more persistent issue than his own blackness.

While Douglas ruled on behalf of Britain and identified with it and its empire, he had very little direct experience of the place itself, and made the one trip of his adult life to Britain on his retirement in 1864. Douglas stayed in occasional touch with his Guyanese relatives, and was part of a social circle where biographical connections to the Caribbean in general and Demerara and Berbice in particular were far from uncommon.

One of Douglas’s sons-in-law, Alexander Grant Dallas, was Berbice born, and in the 1870s the husband of Douglas’s niece was appointed Colonial Secretary of British Guiana. Douglas welcomed his sister Rebecca, her husband and daughter to Victoria from Georgetown in the early 1850s. But by the time Douglas’s daughters inherited part of his grandmother’s estate in the late 1860s, he had no active contacts in the place of his birth.

In the 1810s, James Douglas moved from Demerara to Scotland and then to Lower Canada. His work in the fur-trade took him throughout places that would later become Canada. His migration had a very different meaning than that of the countless Guyanese that have joined the diaspora of the last couple of decades, whose lives are often the subjects of this column.

The punishing divide between the Global North and South, one that is replicated by the divide between Canada’s settlers and her Indigenous peoples, had yet to be built. Global inequalities were enormous and devastating, but had different contours than do todays. So did global connections and solidarities.

The nineteenth-century imperial world tied the peoples of Demerara to those of northern North America by putting them under the formal political authority of the British empire and organizing their economies around emerging global capitalism, whether it relied on enslaved and indentured labour to produce sugar or on Indigenous economies and unfree migrant labour to produce furs. Simple human histories and connections – of journeys undertaken, of marriages made, of lives lived – also tied together the colonies that would eventually become Canada and those that eventually would become Guyana. People whose lives, identities and politics are made in the Guyanese diaspora of today are inheritors of a long, remarkable, and complicated history.

For further reading suggestions, or if you may have any additional information on James Douglas or his family, you can write to Adele_Perry@umanitoba.ca