In the “Ethics of Advocacy” by Lord Macmillan is to be found this passage:

“The code of honour of the Bar is at once its most cherished possession and the most valued safeguard of the public. In the discharge of his office the advocate has a duty to his client, a duty to his opponent, a duty to the court, a duty to the State and a duty to himself. To maintain a perfect poise amidst these various and sometimes conflicting claims is no easy feat.” The pros and cons of practice at the Bar are stated as follows by the Senate of the Inns of Court and the Bar.

“The Bar is a profession for the individualist: It is highly competitive; it calls for hard work, strength of character and a strong constitution. It is not a career which offers optimum security, fringe benefits, a regular salary or the prospect of predictable advancement with the automatic benefit of a pension at the end of the day. The risks are substantial and although the gross financial rewards can be as high as in most other professions or occupations, a barrister has heavy expenses such as chambers’ rent and overheads, travelling expenses and clerks’ salaries, all of which he has to find out of his own pocket, in addition to providing for his own retirement pension. As against all this, the Bar offers the satisfaction which comes from personal achievements in a highly competitive profession which is mentally and physically demanding; in which the rewards are dependent upon individual enterprise and skill and which seldom lacks interest, because it touches upon so many aspects of daily life and involves contact with people of so many different kinds.” Advocacy is essentially the art of persuasion. It is the advocate’s purpose to persuade magistrates, judges and juries to arrive at a conclusion that is favourable to his client. In this talk the masculine includes the feminine.

When the young lawyer emerges full of enthusiasm out of one of the Law Schools, he will soon discover how green he is in the practice of the law, because the art of advocacy and the application of case law to various sets of facts and circumstances can be learnt only in the school of experience.

Good conduct at the Bar becomes both desirable and obligatory, not merely because it is in keeping with traditions that reach back centuries past, but also because we live in a society where standards are falling, where values are changing or are no longer cherished and where discourtesy is the norm.

An attorney-at-law must prepare and present his client’s case and must bear in mind that to every client his case, however small, is the most important. Counsel therefore should treat each case as important. He must give priority to his client’s interests and endeavour within all ethical limits to be successful. He must leave no stone unturned and no avenue unexplored. If his client has no reasonable chance of success, he ought to advise him against instituting legal proceedings; and where his client is sued and appears to have but a weak defence or answer, he ought to try and settle the matter on as favourable terms as possible.

As an advocate in Court a lawyer must be able to deal with every facet of a trial. He must be prepared to open his case, to examine, cross-examine, and re-examine witnesses, to raise points of law and address the Court at the close of the evidence.

There are some lawyers representing plaintiffs who do not open their case or who do so only perfunctorily. It is rare in Guyana for Counsel for the defendant to open his case but he has a right to so and in some cases ought to do so.

An opening speech should be clear and accurate. It should contain the material parts of the evidence in chronological sequence and should make reference to important documents, letters, plans and transports. The issues of the case, as defined by the pleadings, should be brought to the attention of the Court. The authorities on which Counsel relies should be cited. If this is not done, it means that when Counsel for the plaintiff has cited in his final speech authorities which he did not put forward in his opening speech, Counsel for the defendant will have the right to make observations on these authorities.

The importance of the opening speech cannot be over-estimated. If made clearly, with a mastery of details and with a confident air, it can condition a judge’s mind in favour of the plaintiff and can also weaken the self-confidence of opposing counsel. I well remember a civil trial some twenty-five years ago when I was still a junior counsel and was opposed to a leading silk who had the reputation of settling his cases on the basis of full judgement and costs. I was not too happy with every aspect of my case but I prepared and opened my case very meticulously and with an air of great self-assurance and confidence. Immediately, the learned judge of revered memory turned to my opponent and told him that if the case were tried to a finality, he would not know where the hammer would fall. Before lunch there was a settlement, which satisfied my client.

The value of an opening speech depends on the amount of time and effort expended by Counsel in the preparation of his case. One can always tell whether Counsel has paid serious attention to his case from the way he opens his case or fails to do so.

As regards examination-in-chief, this is in some respects a more difficult art than cross-examination because the manner in which questions are put is circumscribed. The whole idea is not to ask leading questions but to elicit from one’s client and his witnesses all the material points in his favour while at the same time strictly adhering to the rules of evidence. How not to examine a witness in chief is normally demonstrated every Friday in the divorce court, where petitioners normally answer “yes” or merely mumble during their testimony. 1 feel that some recent day judges, unlike those before whom I appeared in 1948, are too ready to grant dissolutions of marriage without ascertaining the truth. The easy break-up of family life is bad for society.

If the art of examination-in-chief is mastered, then counsel will have gone a far way in establishing his client’s case. But in order to do so he should know what material facts he has to prove and should carefully go through his proofs with the witnesses. It is always prudent to refresh a witness’ memory before a trial by letting him read over his statement or reading it to him and asking him questions, because such are the law’s delays that a witness may have given his statement months or even several years before the trial. I have always found it useful to explain in simple terms to parties to litigation what are the main issues at the trial and the material facts on which their cases are based. They then appreciate the line of cross-examination of opposing counsel and know how to meet it. Needless to say, it will be quite improper for any lawyer to tell a witness to give evidence contrary to his oath. It has been said that it is the lawyer’s duty “to extract the facts from the witness, not to pour them into him, to learn what the witness does know, not to teach him what he ought to know.”

It was said of Thomas Erskine, an English advocate with a reputation for persuasive eloquence, that “when he had to examine in chief- not as in common fashion following the order of the proofs as set down in the brief-seemingly without art or effort, he made the witness lucidly relate, so as to interest and captivate the jury, all the facts that were favourable to his client.”

The more difficult and delicate task of re-examination he was in the habit of performing with equal dexterity – not attempting clumsily to go over the same ground which he had before trod, but, by a few questions which strictly arose out of the cross-examination, restoring the credit of his witness and tying together the broken threads of his case.

I may add that one main purpose of re-examination is to elicit explanations from the witness of statements made by him in cross-examination, which, if left alone, would be damaging to one’s case. To accomplish this purpose calls for great skill as one cannot put words into the witness’s mouth and at the same time one has to make the witness understand the purpose of the questions and jog his memory.

Young counsel sometimes gets the worst of it. The story is told of a young lawyer in England who was opposed to experienced silk. When he rose to cross-examine the witness he was extremely nervous but, much to his amazement, he discovered that he was making great inroads on the evidence. When silk rose to re-examine, he told his witness: “What you meant to say was so and so”. Young counsel was appalled and rightly objected. The judge yawned and said that perhaps counsel might have put his question differently but he saw no harm in it.

When it was his client’s turn to give evidence young counsel found that his client’s testimony was being severely shaken in cross-examination and so he adopted his older opponent’s technique and in re-examination told his client “What you meant to say was so and so”. The Judge became irate and said: “Mr. X, I am wondering whether your conduct amounts to contempt of court or to professional misconduct, but because of your youth and inexperience I shall do nothing on this occasion.”

I am leaving the art of cross-examination for the last and shall now proceed to counsel’s closing speech. If it is a civil trial, then counsel will address the judge more tersely on the facts than he will address the jury. The reason is that some judges make up their minds early on the facts and, having made up their minds, find great difficulty in changing their minds. This judicial attitude is clearly wrong, because addresses are an integral part of a trial and counsel may advert the Court’s attention to salient points of the evidence, which may not be fully appreciated or may have been misunderstood or even forgotten. It must not be overlooked that counsel, having prepared his brief long in advance and having gone over the evidence with a fine tooth comb, is in a better position to appreciate his own case than the judge.

However, counsel should state his legal propositions in the form of submissions and support them, where they are not trite, by authorities.

It is not necessary for him to catalogue all the authorities on a particular point. He may content himself with citing the highest authority on the point, or the leading case or the locus classicus. When citing an authority, he must do so in the proper form and manner. He should not say, for example, “[1938] L.R.B.G. page 50”; he should say “[1938] Law Reports British Guiana, page 50”. He should not refer to a judge as “Smith J”; he should say “Mr. Justice Smith”. Some judges are also guilty of these lapses. He should pronounce Latin and French words in the accepted lawyer’s manner. For example, he should say “ratio decidendi”, “prima facie”, “coram lege loci” and “cestui que trust” in the manner in which these words have been traditionally pronounced in the English courts and not as if they were classical Latin terms or current French words.

In his final address an attorney-at-law must never express his own opinion. Some young lawyers, addressing a Court, say “In my opinion”. This approach is wrong. A lawyer makes submissions. In doing so he is acting professionally. He is objective and his emotions are not captive of his client’s cause. He will not make impassioned personal appeals. He is not his client’s servant or tool. He merely represents the client’s cause but is no chameleon or weather-cock. The late Justice Wills of revered memory always advised lawyers not to identify themselves with their clients’ cases.

It must not be forgotten that a lawyer must eschew his own prejudices and opinions and formulate only those arguments that will impress the particular judge. One can never be certain that an action tried before Mr. Justice Smith will result in the same judgement as if it were tried before Mr. Justice Jones, just as in the same way the jury sitting in Court 2 may deliver a different verdict from the jury empanelled in Court 3 if the same evidence is adduced as it affects the same prisoner at the Bar.

The technique of advocacy in a jury trial is, of course, different from that in a civil action. From the start of a jury trial, counsel should focus his attention on the manner and demeanour of the jurors, their individual reactions, their whispered conversations during the evidence and the questions that they ask through the Court. A jury is seldom homogenous in education, upbringing and social outlook, so that counsel in addressing a jury must cater for the variety and disparity of their reasoning. He is forced to explain his main points several times in different ways and sometimes to address small groups of them in turn. One juror may be a university graduate, another may be quite unlearned; one juror may favour a particular political party more than another; one juror may be a member of a charismatic group, another may be a communist. Counsel has to appeal both to their reason and their emotions at the same time. This is a technique that calls for great skill, practice, human understanding and empathy.

I turn now to the art of cross-examination. Many members of the public and some lawyers are of the opinion that cross-examination consists of examining crossly and that a lawyer has to be pugnacious, rude and boorish. But the attorney-at-law who wearies the judge and the jurors with protracted and irrelevant cross-examination, who constantly gives way to excitability and loses his temper, who is prone to take advantage of witness or counsel, soon prejudices his client. On the other hand, the lawyer who possesses a genial personality, who speaks with candour and is courteous, who seems to be a seeker of truth and knows his facts, obtains sympathy for his client. It was said of Lord Carson at the Bar that his manners were always quiet.

When a witness is giving evidence in chief, the cross-examining counsel should observe him carefully to see whether he gives any indication that he is lying or trying to conceal any material facts. Counsel should look at his hands, his face, his every movement and expression. Perhaps, when he is lying, the witness tries to swallow or nervously twitches his hands or lowers or raises his voice. Is his evidence shaded or slanted? Has he a personal interest in the result of the litigation? Has he some tangible or ulterior motive to lie? Is he partisan? The witness may have had the best opportunity to observe the facts and yet may lack the powers of observation to take advantage of this opportunity. He may be confusing the evidence of his eyes with hearsay and with impressions. He may not be able to retain accurately what he has seen or heard.

I now wish to give a few hints to young lawyers. In cross-examination the witness’ mistakes should be drawn out indirectly because he would not wish to contradict himself directly. If the witness is loquacious or garrulous, encourage him to speak and involve himself. If he gives a favourable answer, pass on to the next question and do not give him the opportunity to correct, modify or retract it. Unless a lawyer is sure of the answer, he should not ask a really critical question as an answer to such a question may destroy his client’s defence. If the cross-examiner wishes to secure favourable answers, he should wait until the witness seems to be in a responsive mood. On the other hand, the cross-examiner may think it wise to ignore the evidence in chief and attack the witness’s credit but he must do so with propriety: if he makes a damaging imputation, he must have his proof before hand. For example, if he suggests to the witness that he had a criminal conviction, he must have a certified copy of such conviction in his possession.

If the witness is fabricating a story, ask him to repeat his story. He may do so word for word.

Then cross-examine him out of sequence. Take him to the middle of it, then jump him to the beginning and then to the end.

If the witness is really hostile, ask him a question as if you want a particular answer when in fact you want a different answer. If you get a really favourable answer, sit down.

In cross-examining an expert, one has to make a thorough study of the subject matter beforehand and then bring out such scientific facts as will help one’s case. It is not advisable to make a frontal attack on his evidence.

If you have documentary evidence, such as letters, affidavits or previous statements, to contradict a witness, do not produce them to the witness immediately but let him first repeat the statements in his direct testimony which his documents contradict so that he would have no room to re-examine and to wriggle out with explanations.

A cross-examiner may try to obtain an admission from one witness, another admission from a next witness and so on and then in his address string together those apparently insignificant admissions with startling effect.

Attack the witness at the weakest point of his story and stop your cross-examination when you have wrung a favourable admission.

Generally speaking, do not cross-examine a witness who has said nothing material against your client. Such silent cross-examination may not excite your client’s admiration but may secure his freedom. Some witnesses do not volunteer evidence and a wily examiner deliberately refrains from putting the necessary question so that his inexperienced but over-enthusiastic adversary may fall into the trap and ask it.

For example, in the autobiography Some experiences of a Barrister’s Life, Sergeant Ballantine gives an account of the trial of a young woman for murder of her husband by poisoning. The expert witness testified that only a minute quantity of arsenic was discovered in the deceased’s body, and the trial judge summed up the case in favour of the prisoner. Later, it transpired that had the expert been asked the question, he would have proved that the amount of arsenic that was found indicated under the circumstances detailed in evidence that a very large quantity of arsenic had been taken. Discretion is the better part of valour and one indiscreet defence counsel who loved the sound of his own voice would have landed his client on the gallows by cross-examining.

Nearly three years ago at a Bar Association dinner at the Pegasus Hotel, I gave an example of a model piece of cross-examination, which was both brief and effective.

A young woman who was the virtual complainant in a rape case had given a simple and convincing story. She said that she was a dairy-maid working on a farm and after the evening milking she had left the barn and was returning home when the prisoner jumped out of the bushes and suddenly attacked and raped her.

Learned counsel for the accused, who realised that craft was superior to pugnacity and that he could not have bullied the witness into self-contradiction, asked only four questions.

The cross-examination proceeded as follows:

Question No. 1: “How much milk were you

carrying?”

Answer: “About a gallon.”

Question No. 2: “How big was the pail?”

Answer: “A gallon pail.”

Question No. 3 “Was the pail full?”

Answer: “Yes.”

Question No. 4: “Did you lose any of your milk?”

Answer: “No.”

The address to the jury of defence counsel was equally brief and consisted of two sentences: “Gentlemen of the jury, the girl lost her virtue but kept her milk. Do you believe she was attacked?”

The verdict was unanimous: Not Guilty. There is another aspect of cross-examination, which is based on the fallacies of testimony. One has only to consider the famous English and local cases on identification, for example/?, v. Turnbull(\916). Professor Swift relates some very interesting experiments in human observation and draws this conclusion:

“My experiments have proved to me that, in general, when the average man reports events or conversations from memory and conscientiously believes that he is telling the truth, about one-fourth of his statements are incorrect and this tendency to false memory is the greater the longer the time since the original experience.”

A certain scene was carefully enacted and the professor’s students were asked to observe it. The witnesses proved to have had little definite knowledge of what actually took place and had an actual crime been committed, their testimony should have had little value. Yet it would have been accepted because they were eye-witnesses.

Generally there are three sides to every story in Court – the plaintiffs or complainant’s, the defendant’s, and the truth. The unthinking magistrate sometimes swallows the prosecution’s version in its entirety.

It is a part of the independence of the Bar that an advocate cannot be sued by his client for negligence in the conduct of his case in Court: vide our learned Chancellor’s decision in Lopes v. Adams & Vanier (1965) 9 W.I.R. 183, the editor’s headnote of which report is not altogether accurate as to the facts but the ratio of which was affirmed in the House of Lords Judgments in Rondel v. Worsley [1967] 3 All E.R. 993 and in SaifAll v. Mitchell & Co. 11978] 3 All E.R. 1033.

The Legal Practitioners Act as amended in 1980 preserves the advocate’s immunity in the conduct of his case in Court.

I now turn specifically to the question of decorum in court. It has truly been said that the whole foundation of justice in Common Law jurisdictions depends on mutual confidence between Bench and Bar.

I wish to emphasise the aspect of mutuality. On the one hand, complete frankness on the part of the Bar is required and the lawyer must not attempt to mislead the Court. How many lawyers accept this principle and draw to the Court’s attention to authorities that do not assist or are against their clients’ case? The principle is stated in Glebe Sugar Refining Co. v. Greenlock Port & Harbour Trustees (1921) 123 L.T. 578 and may be superficially inferred from The Credits Gerundeuse Limited v. Van Weede( 1884) 12Q.B.D. 171.

A famous lawyer in England once incurred the Court’s strictures when he failed to cite an authority which was contrary to his contention but which he had before him on the Bar table. As a matter purely of expediency, when a lawyer wins a case at first instance by deliberately omitting to cite an authority, his client usually suffers in costs in the Court of Appeal and the trial judge later treats him with suspicion and sometimes even with hostility.

It would be improper for a prosecutor at the sessions to struggle to exclude from evidence previous statements that vitally contradicted his star witness’ testimony, and it would be even more startling for the judge to assist in this exercise.

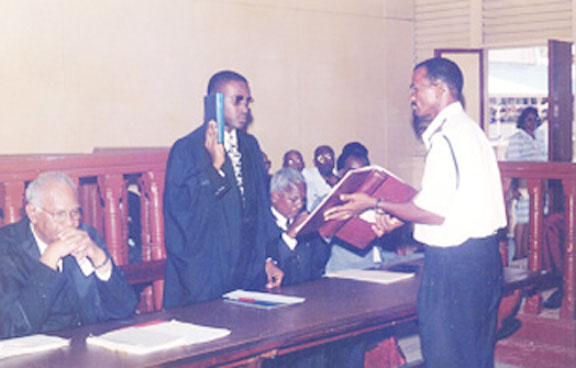

The attorney-at-law should always treat the Bench with courtesy and deference. The respect is shown to the high office, and not necessarily to the particular holder who may for one reason or another incur the displeasure of the Bar or who in rare case may be an unworthy incumbent. Some time in October last [1981] I moved the admission of a young practitioner to the Guyana Bar and was impressed by the words of advice that were given to him by Mr. Justice Kennard who admitted him to practice. The learned judge pointed out that some practitioners did not show the Court the courtesy that they should. They did not bow to the bench when the Judge entered, they dressed in a slovenly manner with their tunic shirts partly unbuttoned and their standards had fallen generally. He said “manners maketh man but dress also maketh the man.” I may add that some lawyers are unaware that they ought always to stand up when they are addressing the Court or when the Court is directing remarks to them.

It is also an act of discourtesy for an attorney-at-law to be absent from Court without leave or to be unpunctual in Court and to arrive after the Judge is sitting on the Bench. In huora v. Reginam (1953), a barrister practicing in Nigeria was absent from Court without permission. Permission to be absent had been granted and then withdrawn by the Court. The Privy Council held that the Barrister’s conduct was discourteous but did not amount to a contempt of Court.

Unless a practitioner has a physical injury he ought not to put his foot on a chair or his hands in his pocket when addressing the judge or jury. He will, of course, obtain a better reception from the Court if he looks at the Judge or Magistrate when addressing him instead of looking at the corridors or the spectators in Court. These are simple points worth remembering.

When addressing the Court, the attorney-at-law should speak clearly, with good diction and correct pronunciation. It is a notorious fact that Guyanese tend to stress the wrong syllables, but at the very least the attorney-at-law should construct his sentences properly so that they can be parsed and analysed and his meaning would be crystal clear. For success in advocacy in Court, command of the English language is as important as knowledge of the law.

It is said that the Bar is the closest of trade unions and in fact there exists a camaraderie at the Bar that is not found in other professions. We all have our offices in the legal square close to one another; we see one another every day in the street, in court and in offices.

Those of us who regularly attend particular country courts have an even closer relationship with our fellows on the particular circuit. Laymen are sometimes astonished that two lawyers can be so disputatious in Court and yet mix so freely and amicably outside of Court. They are very suspicious when two opposing counsel travel in the same car to Court. They fail to realise that we are all friends and brothers in the law. As Shakespeare said in The Taming of the Shrew:

“(They) do as adversaries do in law

Strive mightily, but eat and drink as friends.”

Lawyers should avoid angry verbal exchanges in Court, even if made sotto voce. If they wish to make objections, they should address them to the Court and not to each other. They should not conceal documents that their opponents are entitled to see. Nothing reveals the lawyer’s background more than his conduct in Court. He ought always to act with dignity, decorum and honesty because he is a member of an ancient and honourable profession.

In my 35 years of practice I can recall at least six lawyers who have appeared in Court as advocates in various degrees of intoxication. Those who worship at the shrine of Bacchus during working hours soon lose their clients and forfeit the respect of the public and the Court, and, of course, their own self-respect. They are failing in their duty to the profession and are acting improperly. This addiction to alcohol has also been observed on occasions on the Magisterial bench. Alcoholism is a problem to be solved by doctors, psychiatrists and social workers. On a few occasions I have heard abusive and threatening language used among lawyers in Court and at least on one occasion there was an actual case of assault in the face of the Court.

All these acts – intoxication, abusive and threatening language and physical attacks – are not only frowned upon in ethics, but may bring the lawyers within the pale of contempt of Court. See Re Johnson (1887) 20 Q.B.D. 68 and Ambard v. AG. of Trinidad & Tobago [1936] 1 All E.R. 704.

In Re Johnson, after an application had been disposed of by the judge in chambers, the applicant, who was a solicitor, left the judge’s chambers, and was on his way to the entrance gate of the building. He used insulting language to the opposing solicitor and almost or actually assaulted him. It was held that the applicant had been guilty of a contempt of the court inasmuch as the insults were a gross interference with the administration of justice, and the judge sitting in court had power to commit him to prison for such contempt.

It is also extremely improper, to say the least, for a lawyer to stand by passively in the corridor of the Court and see his client and others commit a flagrant contempt of Court. A lawyer has a duty not to advise or assist in the violation of the law. vide Myers v. Elraan [1939] 4AIIE.RA&4. He is more than a private citizen; he is a minister of the court: See the Canadian case of Re: Martin [1943] 2 D.L.R. 559.

The lawyer who substitutes himself as an attorney-at-law then withdraws the action without notifying counsel who has been appearing therein for years before the Judge is also acting improperly.

On the other hand, I cannot agree that a Judge should find an advocate guilty of contempt of court merely because, on his client’s specific instructions, he has asked the Judge to disqualify himself from sitting in the case, provided, of course, the grounds are substantial, the advocate’s manner is respectful and there are no improper allegations of partiality: see Vidyasagara v. P. [1963] A.C.5S9, a Privy Council decision. It must be remembered that in trial for contempt of court, a Judge is the informant, the prosecutor, the jury and the judge, and there is no right of appeal. He is a judge in his own cause. Memo potest esse simul actor et judex. Happily, such an anachronism has rarely been abused.

In any event, a lawyer cannot be properly found guilty of contempt of court unless he has been given an opportunity to explain his conduct or to show cause: vide the celebrated Privy Council decisions in the Maharaj case and the Jamaica Court of Appeal decision of Re Pershadsingh (I960).

Sir Norman Birkett said that “great advocacy…is in the last and supreme analysis the product of what the man is who produces it.”

There can be no doubt that in the field of law character is more important than ability. As was said by Martin Luther:

“The prosperity of country depends, not on the abundance of its revenues, nor on the strength of its fortifications, nor on the beauty of its public buildings; but it consists in the number of its cultivated citizens, in its men of education, enlightenment and character; here are to be found its true interest, its chief strength, its real power.”

Commonsense is also essential. There is an ancient Persian proverb that a pound of learning requires ten pounds of commonsense to apply it.

I have stressed that counsel should treat the Court with courtesy and deference, but this is not a one way street. Counsel appearing before a Court and acting with dignity and decorum should expect to be treated with courtesy and understanding. I have always maintained that the judge’s deference to counsel is as crucial as the respect that counsel is traditionally bound to show to the judge.

A judge should overrule counsel’s submissions and pass strictures in language that is courtly or Parliamentary; he should not shout or descend to the language of the man in the street; if he desires to maintain respect for his high office he should bridle his temper.

In his essay on “Judicature” Sir Francis Bacon, a former Lord High Chancellor, said nearly 400 years ago that “patience and gravity of bearing are an essential part of justice; and an overspeaking judge is no well tuned symbol. It is no grace to a judge first to find out that which he might have heard in due time from the Bar, or to show quickness of conceit in cutting off evidence or counsel too short so as to prevent information by questions, though pertinent.”

And judicial officers should, like Julius Caesar’s wife, be above suspicion, otherwise they would not command the admiration and respect of the Bar. They should be scrupulously honest and should resent any attempt to interfere with their independence. Integrity and judicial independence are the twin pillars of justice. Sir Francis Bacon disgraced his office by receiving gifts, which was the custom of the day. For both the advocate and the judicial officer a good name like a virtuous woman is worth more than rubies. As was said by Iago in Shakespeare’s Othello:

“Good Name in man and woman, dear my lord, Is the immediate jewel of their souls.”

In keeping with the highest traditions of the Bar, lawyers in third world countries are bound to appear for any client regardless of his political affiliations provided he is paid his retainer fee, normally practises in the particular Court, and is not otherwise engaged. When he does so appear, he expects as of right, to be treated with the same courtesy as any other lawyer. In his address to the profession at a dinner some years ago at the Pegasus Hotel, Lord Denning called upon lawyers in third world countries to accept cases against the State so as to maintain the rule of law.

I now turn to the last aspect of my talk, namely the preparation of cases. It is because a lawyer has made a special study of the law that the public turns to him for guidance through the labyrinths of the law.

The attorney-at-law who practises in Guyana suffers from special difficulties. There are no volumes of Guyana law reports of cases decided over the past fifteen years; the foreign exchange situation is so tight that it is either impossible or hardly possible to purchase new reports and new textbooks; the High Court library was in disarray for a substantial period.

What is required is a system of annual restatement of the law. Why is it necessary for a lawyer to dig into ancient law reports to see what the law is? I sometimes feel that this is a waste of time.

The preparation of cases will depend on whether they are criminal or civil. In a sense the preparation of cases starts with the study of law in one’s student days. But it is perhaps more important to know where to find the law than to know the law, because Courts wish you to quote chapter and verse so to speak.

A criminal case in the Magistrate’s Court may be a summary jurisdiction case, a preliminary inquiry or an inquest. The first thing that the lawyer should do is to inquire into the facts and take statements from his client and witnesses. The client may be uncooperative. He may simply say that he does not know of the incident and he was not there, but a blank denial does not help the lawyer, who will be completely unprepared for the testimony of the witnesses in Court. Suppose your client is charged with break and enter and larceny. He may deny that he was at the scene or that he was in possession of any stolen articles.

How do you find out about the case? You may ask him what allegations the police made to him at the station after they arrested him -what did they tell him he had done. He might say that the police told him nothing. If you then tell him that you are not prepared to represent him, he may then decide to tell you that the police said he was seen running from the scene in the early hours of the morning, so you will begin to understand the case. However, you will keep probing. You may ask the police prosecutor what are the allegations against your client. He may tell you in exaggerated form. The police always believe that they have brought a water-tight case until all the holes become apparent and start leaking.

You must picture yourself in the prosecutor’s shoes and visualise how he will try to prove the case, and what material elements he has to establish. In that way you are prepared to explore any weakness and, if necessary, submit that the evidence is insufficient or unreliable, as it often is.

Mastery of the facts, mastery of the rules of evidence and mastery of the techniques of cross-examination with some knowledge of case law will often result in success. While a lawyer cannot knowingly put forward a false alibi or a false defence, he can take advantage of every weakness and every gap in the prosecution’s case and submit that the offence as laid has not been proved.

At the trial of Courvoisier, a Swiss valet for the murder of Lord Russell (1840) 173 E.R. 869, the accused Courvoisier stood in the dock on the second day of the trial and beckoned to his counsel Charles Phillips. He said: “I wish to tell you that I did kill Lord Russell.” Barrister Phillips, who had undertaken the brief in the belief that Courvoisier was innocent, was shaken by the unexpected disclosure. He sought an adjournment.

C&\e£ i\jst\ce Tya&aW N*as iftve, iprcsv&mg, ju&gc «w& \ifc.TOEv^«fo& ‘•was ^ftfc

junior judge at the trial but was not trying the case. Mr. Phillips consulted Baron Parke in Chambers and was advised that since Courvoisier insisted that he should represent him, he should continue to do so as vigorously as possible and by all fair means but must refrain from casting guile on any other person.

In relation to preliminary inquiries, it is sometimes wise to cross-examine sparingly unless the cross-examiner feels that he can so tie the witness in knots that he cannot extricate himself at the Sessions. But on the whole, too much cross-examination is more dangerous than too little and is counter-productive. Surprise is an important weapon at the Sessions.

At an inquest a coroner asks the question in chief and sums up the case and so the cross-examiner may find himself under restraint. When the indictment reaches the Sessions, the lawyer has the opportunity to analyse the depositions very carefully and to weigh and sift the evidence. He should scan the evidence for contradictions, discrepancies, improbabilities and lies and should be prepared to discredit the testimony of the witnesses and to adopt a line of defence, which he will not disclose too early.

He should also make a written note of the possible grounds of appeal that often arise from the judge’s rulings and his misdirections or nondirections in the summing-up. Many a conviction has been quashed in the Court of Appeal.

If the matter reaches the Court of Appeal, the lawyer should carefully scan the notes of evidence and the summing-up; in particular he should examine the trial judge’s directions on the law and compare his directions on the facts with the actual evidence. He should be prepared to attack the judge’s jurors and do so with the greatest respect. He should not indulge in an argumentum ad hominem unless he is alleging partiality. See Vidyasgara v. R. [1963] A.C. 589. In the same way that many Guyanese lawyers are excitable in their advocacy, some Guyanese judges become excitable and even irritable when conducting criminal trials. Defence counsel may even get the feeling that he is being unfairly treated as an accessory after the fact. In the Court of Appeal, counsel for the appellant should list and collect his authorities well in time. Unlike the Privy Council, the Guyana Court of Appeal has a penchant for citing a plethora of authorities in its judgements. This is not necessary, but is certainly useful to attorneys-at-law.

In the preparation of civil cases in the High Court, the attorney-at-law should have a thorough knowledge of the High Court Rules, the Matrimonial Causes Act and Rules and of the Supreme Court Practice. An adequate study of these rules makes a world of difference as so many objections can be taken. Pleadings play an important part in civil cases in defining the issues.

I well remember a case some twenty years ago when I telephoned an older counsel on the other side and asked him whether he had any objection to an application for a slight amendment of my defence. He thought the amendment was innocuous and readily agreed but he lost his action before the then Chief Justice as a result of it as it had shifted the onus of proof on a particular issue. It was a very narrow escape for my client. It can thus be seen that good pleadings can lay the foundation of victory and bad pleadings can be a prelude to defeat.

As was pointed out by our learned Chancellor in his judgement in the Court of Appeal case of Hassan v. Yacoob, “more often than not there is in every case a cardinal point around which lesser points revolve like planets around the sun.” The civil lawyer should do research on this cardinal point and gather up his authorities. It must not be forgotten that civil law is a more extensive field of learning than criminal law, that the techniques of civil litigation are different from those of a criminal trial, that the atmosphere in a Civil Court is less electric and that the type of cross-examination and arguments that will appeal to a jury will not necessarily impress a judge.

In civil appeals, counsel should check the issues on the pleadings, the state of the evidence and the findings of fact of the learned trial judge. Assuming that the findings of fact are supported by evidence, one has to accept them as correct for the purposes of the appeal unless there is some compelling circumstance or telling factor.

Counsel is, however entitled to criticise erroneous inferences drawn by the judge from the primary findings. Then counsel will examine the judgement for errors in law. It is always useful to make a written summary of legal submissions supported by references to pages and lines. But these should not be read or recited as if by rote. The process of argument in court between a well prepared attorney-at-law and a keen judge is a creative one.

The importance of a thorough preparation of cases cannot be overestimated. It was Daniel Webster who said:

“Accuracy and diligence are much more necessary to a lawyer than great comprehension of mind or brilliance of talent. His business is to refine, define, split hairs, look into authorities and compare cases. A man can never gallop over the fields of law on Pegasus nor fly across them on the wings of oratory. If he would stand on terra firma, he must first consent to be a great drudge.”

I must confess that I sometimes find the business of refining, defining and splitting hairs to be a silly exercise that is fit for clever University students, the result of which often surprises litigants.

What interests me is that a lawyer, unlike a judge, comes into actual contact in his Chambers with various people who bring a variety of human problems: a man’s complaint against the escape of fire or water or cattle from his neighbour’s yard; a girl’s illness after drinking a bottle of ginger beer with a snail inside it; a young woman’s sudden death after the surgeon forgot to remove cotton wool from an internal organ; a child allegedly developing necrosis after being smeared with an ointment; two neighbours quarrelling over the ownership of mangoes on an overhanging branch or a right of drainage and irrigation.

In Regina v. O’Connell, Mr. Justice Crampton said in 1844:

“The Court in which we sit is a temple of justice; and the advocate at the bar, as well as the judge upon the bench, are equally Ministers in that temple. The object of all equally should be the attainment of justice. Now justice is only to be reached through the ascertainment

of the truth.” The goodjudge then advised as follows:

“Let us never forget the Christian maxim ‘That we should not do evil that good may come of it’”

The learned judge considered the suggestion that the advocate was the mere mouthpiece of his client and said:

“Such, I do conceive, is not the office of an advocate. His office is a higher one. To consider him in that light is to degrade him. I would say of him as I would say of a member of the House of Commons – he is a representative, but not a delegate. He gives to his client the benefit of his learning, his talents and his judgement, but all through he never forgets what he is to himself and others.”

“He will not knowingly mistake the law; he will not wilfully mistake the facts, though it be to

gain the cause for his client.”

“He will bear in mind that if he is the advocate of an individual and retained and remunerated

(often inadequately) for his valuable services, yet he has a prior and perpetual retainer on behalf

of truth and justice; and there is no Crown or other licence which, in any case, or for any party

or purpose, can discharge him from that primary and paramount retainers.”

Many qualities, therefore, are needed in the make-up of a good advocate or of a good judge or magistrate: legal learning, proficiency in the use of English, flexibility, commonsense, charisma, wit and humour. But above all I put character. I would rate good character wedded to average ability above extraordinary talent coupled with an untrustworthy character.

Before I take my seat I shall end my talk with these famous lines from

WOTTON:

“How happy is he born and taught,

That serveth not another’s will!

Whose armor is his honest thought,

And simple truth his utmost skill!

“Whose passions not his masters are,

Whose soul is still prepared for death!

Untied unto the world by care, of public fame,

or private breath!

“This man is freed from servile bands,

Of hope to rise, or fear to fall!

Lord of himself, though not of land!

And having nothing, yet hath all.”

A paper delivered at a Guyana Bar Association Seminar held on November 21, 1982, by the late B.O.Adams