LASANA LIBURD says despite the recent damage done to the CFU, Caribbean Football is moving forward on a stronger footing.

Conceit, according to United States sales guru Zig Ziglar, is the one disease that makes everyone sick except the one who has it.

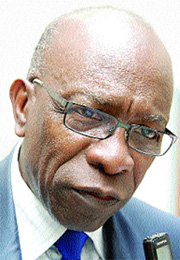

The ambition of former CONCACAF and Caribbean Football Union (CFU) president Jack Warner knew no bounds. His sycophants, spread across most of the 25 CFU member nations, bought into Warner’s swagger and the suggestion that he and FIFA were the same.

Was it always smoke and mirrors? Was it a Ponzi scheme of sorts in which influence was leveraged to create political strength and then cashed in?

Warner convinced the Caribbean that he and not FIFA President Sepp Blatter was the most powerful man in football. But, sold on his own hype, he overplayed his hand. It was not enough to be seen as influential. The Trinidad and Tobago citizen decided to actually influence the June 2011 FIFA Presidential elections.

And then, before you could say “bribery”, the game was up.

Warner resigned in the face of FIFA’s “overwhelming evidence” that he conspired with disgraced ex-FIFA Presiden-tial candidate and former Asian Football Confederation (AFC) President Mohamed Bin Hammam to bribe CFU associations in the buildup to the election.

Bin Hammam was banned for life on July 23 although a final verdict is yet to be reached on the fate of 16 CFU officials from 11 different associations who were deemed to be either uncooperative or dishonest with FIFA’s investigators.

Nearly four months since Bin Hammam’s infamous trip to Port of Spain, the CFU has apparently been reduced to an afterthought. But will Caribbean football similarly crumble without the man they called “Teflon Jack”? The answer is yes but mostly no.

The system of power that allowed 25 Caribbean nations with a total of four World Cup final berths between them-one each for Haiti, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and Cuba-more clout than South America always seemed incongruous. Democracy irked the more established football nations.

Arguably, the greater sin was in the fact that the Caribbean’s elevated status on FIFA’s political ladder rarely translated into tangible support for the regional teams.

Trinidad and Tobago came within a point of the 1990 World Cup and then went a step further in 2006, Jamaica qualified in 1998 while St Vincent and the Grenadines, St Kitts and Nevis and Barbados enjoyed periods of relative success in between. In almost every case, the financial rewards for their positive showings was not administered in a way that would benefit the island’s football structure or never made it into the coffers of the respective associations at all.

Islands pocketed millions from FIFA grants and developmental programmes without properly accounting for its use.

Nearly half the member associations charged with improper conduct in relation to the Bin Hammam bribery scandal have not played a single international game in this calendar year. And yet there they were with hands out for oil money as they mused over the possible identity of the next FIFA President.

Apart from FIFA mandated fixtures, the Dominican Republic has not played a football match since October 8, 2008 when they were trounced 9-0 away to Trinidad and Tobago.

Their officials, Osiris Guzman and Felix Ledesma, should have been facing sanctions, not being offered brown envelopes stuffed with cash.

The last friendly international played by Bahamas was in 2003 when they lost 6-0 to Haiti. Turks and Caicos has not arranged its own football match since a 3-0 loss against the Cayman Islands on September 27, 2000.

The Caribbean also boasts the worst team in FIFA. Montserrat is at the bottom of the football ranking alongside Andorra, American Samoa and San Marino. And the tiny island has only ever played one friendly in 12 years as a FIFA member.

It probably wouldn’t matter to these islands if the FIFA Vice-President was Jack Warner or Jack the Ripper.

Dwight Yorke, the Caribbean’s most celebrated football star, might be Warner’s compatriot but there was precious little benefit gained from that fact.

A former record signing at Manchester United, Yorke, who retired two years ago, is the 10th highest England Premier League goal scorer of all time and is the competition’s top non-European scorer – Frenchman Thierry Henry and Dutch striker Jimmy Floyd Hasselbaink are the only non-English players to manage more items than he did.

Yet, for all those achievements, Yorke does not have so much as a plaque from the Caribbean Football Union (CFU) for his contribution to the game. Rather, Warner once called him a “cancer to the game” after the player pulled out of a friendly fixture.

So, FIFA’s body blows might be fatal to the political structure of Caribbean football. But then the CFU rarely gave the suggestion that its role was to celebrate regional football talent or mould proper football teams.

Formed in 1979, the CFU didn’t hold a football tournament for ten years. And, when it did in 1989, it was a pre-launch party as Warner consolidated his base before making a successful run at the CONCACAF helm, a year later.

Maybe it wasn’t even Warner’s idea.

In Warner’s biography, he credited American Chuck Blazer for the blueprint of his charge to power. On the eve of the CONCACAF presidential election, FIFA President Joao Havelange personally canvassed the delegates in his hotel room.

When Warner became CFU president in 1983, ten of CONCACAF’s 22-member associations were from the Caribbean and the islands felt that the Confederation’s Mexican President Joaquin Terrazas was intentionally keeping them at bay. But, in 1988, Havelange welcomed three new Caribbean nations into the FIFA family and the stage was set for Warner’s ascendancy.

In the next decade, eight more Caribbean nations joined FIFA while Bermuda, the Bahamas and Puerto Rico left the North American zone to participate with the CFU also.

There were now 25 CFU members of the 35 CONCACAF associations.

But Warner’s attempt to replace Sepp Blatter—if that was indeed his intention—brought down the house of cards. Fittingly, Blazer, the man who made him king, was his executioner.

Former interim CONCACAF President Lisle Austin attempted to remove Blazer within a week of inheriting Warner’s responsibilities but was quickly scythed down by the American. At present, Austin, a Barbadian, is suspended by FIFA for attempting to reverse Blazer’s decision in court.

The court, incidentally, backed Austin. Not for the first time, FIFA ignored the law.

Within weeks, Blazer claimed to have wooed 10 of the 25 CFU associations.

Today, 14 of the region’s associations have made their peace with the new power structure and the CFU barely exists on paper-even staff members claimed to be unsure about where the Caribbean body is registered.

So, the body that permitted a former Trinidadian school teacher to have photo opportunities with living icons and world leaders is now a stiff.

Caribbean football is not necessarily dead and buried, though.

With the likes of Kenwyne Jones (Stoke City and Trinidad and Tobago), Ricardo Fuller (Stoke City and Jamaica) and Jason Roberts (Blackburn Rovers and Grenada) competing at such a high level, the Caribbean talent pool is not shallow. The replacement of the current crop of incompetent and disinterested administrators should help the respective nations to fashion decent teams around such stars and better their chances of creating superior replacements.

At the least, the abuse of the dreams of athletes and fans throughout the Caribbean should end.

Warner was knocked down by his own runaway ego and nearly half of the region might suffer a similar fate. But Caribbean football can still lift itself from the abyss. Reprinted from the Trinidad and Tobago Review