Two days ago Trinidad and Tobago observ-ed a national holiday. It was Shouter Baptist Liberation Day celebrated annually on March 30 to mark the anniversary of the day when the ban on Shouter Baptist worship in Trinidad was lifted. This day was declared a public holiday in 1996, but it is also the commemoration of a historic fight for freedom of worship and for traditional culture in the Caribbean.

This struggle and its cultural implications have also been immortalized in literature. At least two works treat the subject in fictionalised fashion. The first is actually two works: Earl Lovelace wrote the novel The Wine of Astonishment and several years later dramatised it in a play of the same name which was performed to celebrate the anniversary when the national holiday was declared. Rawle Gibbons created Ogun Iaan in 2008.

The Shouter Baptists, Spiritual Baptists and Shouters traditionally practised a form of worship involving shouting, chanting and the ringing of a bell, which the colonials cited in passing the law stating that they disturbed the peace. Ironically, they are sometimes seen as sources of derision by the Trinidad popular society, which is little different from what obtains in Jamaica where such religions as Pocomania are concerned, and in Guyana with the Jordanites. They are, however, serious movements that evolved from hybridity; the revival of traditional African worship rituals and practices. There are many such religious practices in the Caribbean, some with more pronounced African retentions than the Shouter Baptists. Some of them include possession, blood sacrifice (animals), music and dance as part of the rituals, practices which were submerged and then revived under an ‘approved’ Christian church (like the Baptists). Others are even more extreme, like the Shango Baptists, Voodoo and Santeria which translate Roman Catholicism with Yoruba traditions.

A number of these religions are called Revivalist or Spiritualist and the non-Christian elements were submerged either because the Africans considered them secret or because of the disapproval of the colonial authorities and the slave masters. After the ban on the Shouters in 1917 they suffered brutal police beatings, arrests, court action and imprisonment, and many of them continued their worship in the forests or defied the ban in their churches.

Despite resistance and appeals the prohibition was not repealed by the Legislative Council until March 30, 1951. Then following agitation in 1996 Prime Minister Basdeo Panday declared March 30 a national holiday. There had been a persistent campaign for the removal of the ban led by Grenadian born Deacon Elton George Griffith who was made Archbishop of the Shouter Faith from 1951 until 1992. He received legislative support from Albert Gomes and this led to a committee being set up to make a recommendation to the Legislature. The committee reported on August 28, 1950 and the Legis-lature voted to repeal the ban with support from Minister Roy Joseph, well known political and trade union figure Uriah Butler, Ashford Sinanan, Mitra Sinanan and Stephen Maharaj (Trinidad Express, March 28, 2012).

Another memorial to the Liberation is a monument called Sorteria (Latin for ‘salvation‘) a holy shrine standing in the forecourt of the NIS office on Harris Promenade in San Fernando, which is the site of the first Baptist church. It was put up in March 1991 to commemorate “the struggles of the Baptists and their eventual release from bondage to freedom” (Express, March 28, 2012, in a different article featuring the monument). It is 15 feet high in the shape of the cross with its outer arms 40 inches wide to represent the 40th year of the celebration of the release, and an inner black cross 34 inches wide to signify the 34 years of struggle from 1917 to 1951. The cross is the image of Christianity, its base takes the shape of a trumpet signifying the trumpeting and loud shouts. It stands on a stone base of clear terrazzo to represent the clear waters of the River Jordan (the Express).

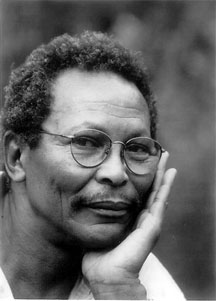

Earl Lovelace, a Trinidadian novelist and playwright with a very keen interest in carnival and cultural traditions tells the story of the trials of the Shouter Baptists in The Wine of Astonishment, the novel which he then dramatized. He takes his title from the Old Testament in the Bible in which the people lament that the Lord “has shown us strange things” and has “made us to drink the wine of astonishment” in punishment for their transgressions. Lovelace suggests that the people in Trinidad were equally punished for their own failure to properly uphold the religion and were therefore visited by plagues and hardships including being deserted by the ancestral spirits.

Lovelace creates a work full of imagery and symbols to fictionalise what happened in 1917 and afterwards in Bonasse Village. He presents parallels between them and the Children of Israel in the Bible. He takes the story through the arrival of the American Naval base in Trinidad during World War II and all the breakdown of law and morality that it released like a plague upon the society. Eventually the ban was lifted but Lovelace suggests that in spite of that the people found that their worship felt hollow and empty as if the spirit had deserted them and elected not to return. He then further suggests that the spirit transferred itself into something else, the newly created steel pan.

In similar fashion playwright Rawle Gibbons touches on the parallel issues in Ogun Iaan. He uses the spirit of the Yoruba god Ogun and tells a story of the birth of the steel pan and the persecution of the people for their cultural traditions. He presents ironic contrasts between the music of the middle class and the working class creations, as well as hostile middle class attitudes. Added to this are tragic treatments of the social upheavals following the arrival of the Americans, and the police persecution.

These are two important works that provide artistic statements on this part of Trinidadian history. Like the laws of 1951 (the liberation) and 1996 (the granting of the public holiday) they mark the serious significance of the Shouter Baptists to Trinidadian culture and demonstrate a contrasting attitude to those members of popular Caribbean society who ridicule the Baptists, the Pocomania people and the grassroots religions.