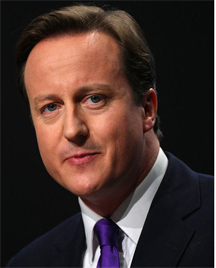

LONDON, (Reuters) – Prime Minister David Cameron rejected the idea of a law to regulate the British press yesterday, risking a split in his government after an inquiry advised legal backing for a watchdog to police the sometimes outrageous conduct of newspapers.

Opposing an independent regulator enshrined in law will delight the British press ahead of the 2015 election but may raise concern inside the coalition government that Cameron lacks the mettle to stand up to media barons such as Rupert Murdoch.

Cameron said he was wary of writing press regulation into law, a snub to the inquiry he ordered in July last year after public outrage at revelations that one of Murdoch’s tabloids hacked the phone messages of a 13-year-old murder victim.

“The issue of principle is that for the first time we would have crossed the rubicon of writing elements of press regulation into the law of the land,” Cameron told parliament, watched from the gallery by victims of phone-hacking who have campaigned for tougher rules to police Britain’s recalcitrant media.

“I’m not convinced at this stage that statute is necessary,” Cameron said, just hours after Lord Justice Brian Leveson reported on his inquiry which laid bare the cosy ties between British leaders, police chiefs and press barons.

Presenting his 1,987-page report opposite the House of Commons, Leveson said he had no intention of undermining three centuries of press freedom but that the press had at times “wreaked havoc with the lives of innocent people” and was sometimes guilty of “outrageous” behaviour.

Leveson said it was essential that there should be legislation to underpin a new independent, self-regulatory body for the press that would be scrutinised by the broadcast regulator Ofcom and have the power to impose fines of up to 1 percent of turnover up to a maximum of 1 million pounds ($1.6 million).

“The ball moves back into the politicians’ court: they must now decide who guards the guardians,” Leveson said.

The behaviour of Britain’s tabloid press has come under increasing scrutiny in recent years. While British newspapers were unwilling to report on King Edward VIII’s affair with American divorcee Wallis Simpson in the 1930s, their conduct has since become much less restrained in the battle for readers.

As competition intensified, the tabloids turned on the private lives of the royal family, culminating in feverish coverage of Princess Diana, hounded by paparazzi as her marriage to Prince Charles collapsed.

At one point in the early 1990s, a government minister warned the tabloid press that they were “drinking in the last chance saloon”. At about the same time the Press Complaints Commission was set up, a self-regulating watchdog now deemed to have failed.