Dear Editor,

Congratulations to the Private Sector Commission (PSC) on its outspokenness against the recent actuarial proposals for NIS reform. It is instructive to note the private sector’s emboldened exit from a closet which was (subconsciously perhaps) inhabited at least for the past decade.

Which is what makes the following observation included in SN’s article of December 15, 2012, interesting: “Pointing out there had been minimal changes to the board of directors over the last 10 years, and chairmanship for the last 20 years, the PSC called for reshuffling of the board.”

Some attentive observers may well ask where was the PSC this past twelve years of this century?

The recommendations itemised in the article are worthy of the fullest support. They nevertheless are tinged with a certain belatedness, raising from amongst them the question of the sector’s inaccessibility to, and possible disinterest in, earlier ‘financial statements and actuarial reviews.’

Memory seems to have faded concerning the national series of consultations conducted in 2006 by the NIS board on the last actuarial review. This was followed with the appointment in 2007 of a quite representative NIS Reform Committee including businesspersons, trade unionists, academics, accountants, as well as pensioners’ and consumers’ associations. Their intensive deliberations lasted several months, resulting in a three-volume report, respectively focusing on administration, information technology, and investment strategy. No individual or group has since enquired about its acknowledgement or otherwise by the NIS Board, and/or of its implementation.

The instant vocalisation is therefore most welcome, but should be seen against the background of the past performance of private employers – particularly in relation to the following recommendation mooted by the PSC: “Stiffen and enforce penalties for late or non-payment of contributions, and introduce legal measures such as levying on the income and assets of non-compliant employers.”

Apart from investment income, implementation of the above recommendation is the certain key to the sustainability of the NIS – compliance.

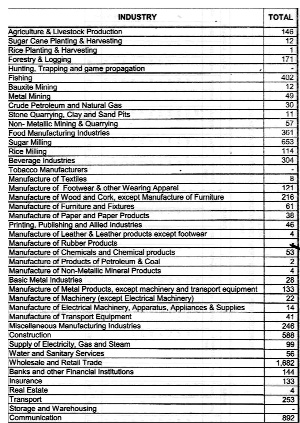

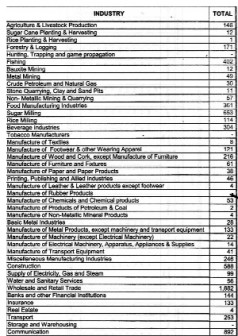

Annexe A hereto is an extract from the Scheme’s 2010 Annual Report which speaks for itself. What is unclear is whether or not the table represents the number of registrants recorded in the one year, or hopefully not, the overall total as at December 31, 2010. In any case it also raises the question of how, in the face of an expanding economy, there is such a significant contraction in contributions. It is for the PSC to identify:

i) the apparent defaulting industries (like tourism and hospitality)

ii) the under-subscribed industries. (GuySuCo alone has 18,000 employees).

There is also reason to wonder why the non-mention of the legal status, and therefore eligibility for compliance, of the increasing proportion of foreign investors, whose delinquencies are not necessarily restricted to this area of accountability.

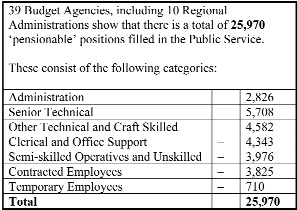

In this connection it may not be totally irrelevant to review the standard of compliance in the public service. Interested parties may therefore wish to extrapolate from the employment figures contained in the 2012 National Budget – concised in the following Table A for easy reference, and for obvious reconciliation by the NIS management with actual contributions received.

Of the above the top 10 employers of ‘contracted’ employees would appear to be the following: Health – 749; Region 6 – 284; GPHC -240; Culture, Youth & Sports – 222; Education – 218; Labour – 138; Region 3 – 135; Agriculture – 129.

Do remember that the public sector includes 40 statutory bodies and 10 state enterprises, as shown in the current National Budget.

But there is one policy dimension to the discourse about which, surprisingly, there has been a resounding silence. A possible explanation may be that private sector employees generally benefit from pension schemes wherein the retirement age is usually 60 years. So the fact that the traditional public service maintains a retirement age of 55 years – an anachronism of colonial history (at least for males), seems to have been obstinately overlooked.

The PSC and colleagues would have done a further service to this community should they press the case for parity of retirement eligibility at the minimum of 60 years in the public service.

Yours faithfully,

E B John