Unfortunately, we cannot cherry-pick the vicissitudes of fortune. Thus, when the PPP came to government in 1992, it inherited both Desmond Hoyte’s Economic Recovery Programme (ERP) and the industrial relations environment it had helped to create to obstruct the ERP’s establishment.

I have argued in this series that when solutions are not found to social problems they tend to fester and recur from time to time in costly ways. The Guyana Public Service Union (GPSU), with which the PPP/C had to deal in 1992, was essentially established in the Burnham era and periodically had its own quarrels with the PNC regime. The attempt by the current rulers to dub the union an arm of the PNC and to control, weaken or destroy it is unwarranted.

Out of power, the PPP had savaged the Hoyte government for bringing penury upon the working people and referred to the ERP as an Empty Rice Pot. The entire quarrel between the PPP/C government and its employees as represented by the GPSU is about the speed with which this pot could be replenished and filled!

As we saw last week, trade unions in Trinidad and Tobago had some success in getting the courts to force the government to repay lost wages and cost of living allowances to public servants. But Guyana was an autocratic state and in these kinds of conditions governments are usually able to implement all manner of unpopular measures without serious political consequences. To the apparent surprise of even the International Financial Institutions (IFIs), Desmond Hoyte was able to beat back the unions without making significant concessions, and in a 1992 report, the World Bank observed that his initiative was: “a major and fundamental reversal” of Guyana’s path and that “Few countries have moved so far, so fast.”

The PPP/C’s coming to government signaled the end of the autocratic state and, among other things, the flowering of workers’ rights. Government employees had been given little relief from the ravages of the Economic Recovery Programme (ERP): inflation was on a downward trajectory (94% in 1989, 80% in 1990, 70% in 1991, 14.2% in 1992 and 7.7% in 1993) but although it was still above 14% in 1991, the PNC government only increased public servants’ wages by 10%.

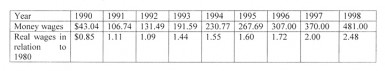

In the years between 1980 and 1989, money wages increased from $11.55 per day to $35.89 per day. However, according to the GPSU position placed before the arbitration tribunal of 1999, taking $4.00 a day, which was paid in 1970, as the base, real wages, which were $4.38 a day in 1980 had been reduced to $1.49 in 1989 and to only $0.85 by the end of 1990. Improving this situation was now the major goal of the GPSU, confronted by a PPP/C government tightly wrapped in the conditionalities of an ERP about which it could do very little.

However, upon coming to government Jagan immediately showed good faith. According to the GPSU’s own documentation, by a “circular dated 13thApril 1993, the minimum wages was increased to $174.17 as from the 1st July 1992 and to $191 as from 1st January, 1993. The real value of the minimum wage at 1st January, 1993 was $1.44, an increase of 69 percent over the low of $0.85 in 1990.”

Real wages were increasing but the GPSU considered this movement insufficient and called strikes between Wednesday 15 to Friday 17 September, 1993 and 11 to 20 May 1994 to press its case for real wages equivalent to those of 1980.

Indeed, ten years later, in 2002, the public service had still not arrived at a real minimum wage equivalent to that which had existed in 1980, and the allies of the union felt that: “The problem with the GPSU in the negotiations with the PPP/Civic Administration is the Administration seems only willing to discuss salary lost through inflation, no doubt inferring that what transpired prior to 1992 is not of their concern. As the GPSU has so often informed the Administration, government is continuous and so are laws, regulations, etc, irrespective of which administration enacted them, unless of course, they are repealed.”

It is here that Jagan played a masterstroke. Given these persistent quarrels about the regime’s capacity to pay greater increases, in February 1997,he showed a commitment to openness in government financing, which, if it was universalized in the public arena, would have transformed the way we view government..

He established a committee consisting of Messrs. Shaik Baksh (Chairman), Winston Jordan, David King, Gobin Ganga, John Seeram, June Ward, Patrick Yarde, Leslie Melville, Clive Thomas, Christopher Ram, Lancelot Baptiste and Earl Welsh to: “To Consider whether the government of Guyana has the capacity to improve the wages and salaries of public servants at present and the ways and means of doing so.”

The scope of the committee’s work appeared all-encompassing. It looked into almost every area of government: the tax system; capital expenditure programmes; efficiency in government operations; public service reforms and sources of funding which could be used to increases public servants’ pay, etc.

In brief, in terms of wages, the committee recommended that the employees on lowest band be given an increase of 25% and those on the highest 15%, provided that the total payout to public servants did not exceed the sum of $333.5 million. The precise percentage increases for the other bands were to be agreed between the unions and Public Service Ministry. Payments were to be tax free and made in two tranches: mid August 1997 and the end of November 1997. The committee also recommended that collective bargaining be restored and that the government and the union should urgently meet to discuss a wages policy that would form a framework for future wages negotiations.

President Cheddi Jagan died on March 6th 1997, about five months before the committee completed its report and a truly transformative opportunity was missed. Some in government claimed that the committee went beyond its mandate and a dispute arose about who were the public servants to benefit from the $333.5 million: the nearly 10,000 usual public servants or the entire 22,500 public employees, including police, teachers, the army, etc.

Have a prosperous New Year.

henryjeffrey@yahoo.com