No fish has ever gotten under my skin quite like the arapaima. Sure these air-breathing “dinosaurs of the deep” are endangered but that Wednesday afternoon at Grass Pond in remote Rewa as dozens of the giant fish rolled in the deep, my patience dissipated faster than the fading sunlight and I rebelliously thought of how good pepperpot arapaima would taste.

Eating a living fossil indeed! Apologies to the good people of Rewa and conservationists all around. My guide Rovin Alvin was amused. Hands on the shutter, on high alert, scanning the dark waters from the canoe in the centre of the lake, I waited for the Arapaima to roll, that is, come up to breathe air. I had imagined huge fish slowly rising from the deep to languidly take gulps of air allowing me to snap numerous photos of these giant creatures and show the world that I rolled with the so-called living fossils. Heck I even imagined a selfie with an arapaima.

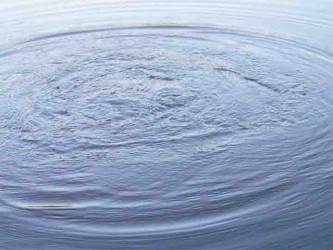

The arapaima had other plans. These were no lumbering dinosaurs. A quick flick to the surface, sometimes a turning tail and they were gone, leaving nothing but concentric waves on the still surface of the lake. Time and again, the arapaima rolled and vanished in less than a second. Time and again the shutter button was pressed a little too late. Don’t worry, Rovin assured. There were, he said, some researchers who came with cameras that took hundreds of frames a second and after numerous attempts, they only managed to obtain a few photos of the arapaima that they could use. That reassured me only a little as I

thought of jumping into the lake and grabbing one and trying for that selfie.

But amidst my rebellious thoughts of arapaima steak, Rovin imitated the call of a caiman in distress and got a responding deep bellow from what sounded like the grandfather of caimans. That did the trick. Arapaimas forgotten for the moment I wondered if a gigantic caiman would come rushing to the canoe to rescue the fake caiman-in-distress. The wooden canoe was small and Rovin had paddled to the centre of the lake. Well, I thought, I’d probably be the appetizer for the gigantic-sounding caiman but there are worse things. Thankfully, after bellowing often in response to the distress call, the grandfather caiman refused to move from wherever he was to rescue his fake caiman-in-distress.

After accepting that the arapaima would not pause for my camera, much less for a selfie and after the initial trepidation following the bellows of the great caiman, I relaxed, breathing in the still, cool air. The sun slowly dipped lower on the other side of the forest, the serenity of the lake broken only by the sounds of wild birds. In the deepening twilight, Rovin turned the canoe around and we glided through the water hyacinth, then into the rainforest for the short hike to the Rewa River. The stars came out, glittering in the soft expanse of space, the Milky Way a river just like the Rewa and as storks grabbed the last fish from the river for supper, we returned to the Rewa eco-lodge where a supper of fish awaited. But not arapaima.

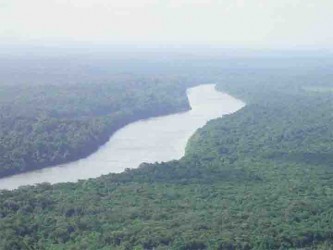

Rewa: at the confluence of the Rewa and Rupununi Rivers where in the early mornings, young, middle-aged and old men sit in their canoes, fishing in the swirling mists. For, it is here where the Rewa runs into the Rupununi that the fish are plentiful.

It was by fortunate happenstance that I ended up in Rewa, in the jungles of Region Nine. I was on a two-fold mission to Apoteri in search for the Domingo girls who, 19 years ago, had survived a month-long ordeal lost in the jungle, watching their uncle die, being stalked by a jaguar and eating peppers to stay alive. I was also there to cover the Baishanlin scoping meeting for the Chinese company’s logging project. Here, many lamented that Guyana’s “last frontier” would be changed forever with large-scale logging and also mining activities.

The “last frontier” description is apt. I have travelled widely across Guyana and the indigenous communities of Apoteri at the confluence of the Rupununi and Essequibo Rivers and Rewa at the confluence of the Rewa and Rupununi Rivers, retain more than most, the traditional ways of living. This is slowly changing but, maybe due to the remoteness of the villages – it is over four hours from Annai to Apoteri overland and then by boat – the change is not yet as drastic as in other communities.

The richness of the biodiversity in the surrounding areas is renowned with the BBC and other international teams filming documentaries there. Rewa, particularly, has a fledging eco-tourism business with tourists coming from Europe and North America to experience the rich biodiversity of the area. But many persons fear that with the area being opened up to logging, the pristine wilderness would soon be gone forever.

It is not easy getting there. You either fly or go by road from Georgetown to Annai then overland for about 15 minutes to the Kwatamang landing then it is four hours to Apoteri by boat on the Rupununi River. I was not sure of the geographical position of Rewa in relation to Apoteri but as luck would have it, Rewa was smack in the middle, half-way between Annai and Apoteri. Having heard a lot about Rewa, upon the completion of my mission in Apoteri, I returned to Rewa and booked into the Rewa Eco-lodge.

Built solely of local materials with thatched roofs and wooden walls, the cabins are reasonably spacious but the best feature was the huge bathroom, half covered and half-in the open so that one could shower under the stars. It is exhilarating: staring up at the stars so bright that they lent a sheen to the sleeping forest, the only sound the water hissing from the shower.

In the morning, an agouti calmly walked the grounds between the cabins and the benabs, looking for the cocorite that fell from the palm trees in the compound. The agouti was not tame but no one looked to capture it. In Rewa, the people understand the importance of conservation and the agouti roamed freely. Others sometimes came too and on my last day, a huge acouri ventured onto the grounds of the lodge but I was in the shower and did not get to see it though the manager told me about it later.

Rewa heals. Going out with Rovin early in the morning for the complimentary climb up the Awarmie Mountain, the calmness of the river, the peacefulness of the jungle was soothing. Scarlet macaws flew overhead and multi-coloured toucans urged each other to fly over the river.

Relatively speaking, the Awarmie Mountain is a little mountain and takes about half an hour to climb, up the steep slopes, under overhanging rocks where roots of trees attach themselves to the rock rather than in soil, past green moss-covered rocks. But soon I was breathing heavily and paused to take photos as an excuse. Rovin, upstanding guy that he is, understood and he paused now and again to explain something. There were the ants whose name I do not recall now but they were used as a means of testing the capacity of youths to endure the pain of the sting as well as a means of discipline. Rovin showed how the ant could grab on to a leaf and never let go.

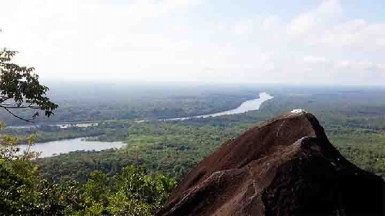

“This is the natural air-conditioning,” Rovin said as we neared the summit and suddenly a blast of cold air swirled around me. It was better than any air-conditioning. The views from the summit were magnificent. On one side, a range of mountains including the Matapee mountain that Rovin as a child was taught not to point at because it would rain. On the other side the green canopy of the rainforest stretched unending until they faded into the hazy distance. The Rupununi River glimmered in the morning sun, a patch of savannah there, yellow blossoms alighting a tree on fire.

This was Rewa, untouched, pristine, and pure. I drank it all in, absorbed the cool, cool air rolling in from the jungle, soaked up the rays of the sun. I thought back to the previous day when persons spoke of the “clear and present danger” facing the area from logging and mining operations. It was disquieting that the pristineness of the area could soon be gone.

All too soon it was time to go. The “dinosaurs of the deep” were waiting below. No one was turning them into supper. Not yet anyway.