The rain set early in to-night,

The sullen wind was soon awake,

It tore the elm-tops down for spite,

And did its worst to vex the lake:

I listened with heart fit to break.

When glided in Porphyria; straight

She shut the cold out and the storm,

And kneel’d and made the cheerless grate

Blaze up, and all the cottage warm;

Which done, she rose, and from her form

Withdrew the dripping cloak and shawl,

And laid her soil’d glove by, untied

Her hat and let the damp hair fall,

And, last, she sat down by my side

And called me. When no voice replied,

She put my arm about her waist,

And made her smooth white shoulder bare,

And all her yellow hair displaced,

And, stooping, made my cheek lie there,

And spread, o’er all, her yellow hair,

Murmuring how she loved me – she

Too weak, for all her heart’s endeavour,

To set its struggling passion free

From pride, and vainer ties dissever,

And give herself to me for ever.

But passion sometimes would prevail,

Nor could to-night’s gay feast restrain

A sudden thought of one so pale

For love of her, and all in vain:

So, she was come through wind and rain.

Be sure I look’d up at her eyes

Happy and proud; at last I knew

Porphyria worshipped me; surprise

Made my heart swell, and still it grew

While I debated what to do.

That moment she was mine, mine, fair,

Perfectly pure and good: I found

A thing to do, and all her hair

In one long yellow string I wound

Three times her little throat around,

And strangled her. No pain felt she;

I am quite sure she felt no pain.

As a shut bud that holds a bee,

I warily oped her lids: again

Laugh’d the blue eyes without a stain.

And I untightened next the tress

About her neck; her cheek once more

Blush’d bright beneath my burning kiss:

I propp’d her head up as before,

Only, this time my shoulder bore

Her head, which droops upon it still:

The smiling rosy little head,

So glad it has its utmost will,

That all it scorn’d at once is fled,

And I, its love, am gained instead!

Porphyria’s love: she guessed not how

Her darling one wish would be heard.

And thus we sit together now,

And all night long we have not stirr’d

And yet God has not said a word!

Robert Browning

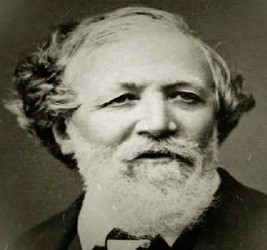

Robert Browning (1812 – 1889) was a master at the dramatic monologue for which he developed quite a reputation. He was one of the foremost English poets of the Victorian period, whose interest in drama and dramatic rendition is not surprising since he was also a playwright. His marriage to poet Elizabeth Barrett is as famous as his poetry. It is said that the marriage did much to boost his career which took off so famously that he became highly celebrated and revered during his lifetime.

A part of his fame arose from the direct relevance of his verse to the Victorian times whose social norms he sometimes interrogated.

Often, as in the case of the poem “Porphyria’s Lover”, the poet criticises these behaviours very severely. It is worth noting how disapproval of depraved attitudes are conveyed through his techniques – particularly the irony which is a major tool of his, creating remarkable poetry in his dramatic monologues.

It is ‘dramatic’ monologue because it is so crafted that although we are only given one voice, the monologue ‘dramatises’ a situation placed in a social context that tell us about the speaker and through him, about the society. We are often made aware of the presence, actions and responses of others even though we never hear them speak. But what rises above all is that part of the craft in which Browning employs narrative point of view. The persona tells us the story from his point of view, but he is often an unreliable narrator because he is very subjective, revealing his own peculiar biases and his inability to separate right from wrong; his readiness to rationalise criminal acts. The reader has to see through him to get the real picture.

Among Browning’s best poems of this type are “My Last Duchess” and “Andrea Del Sarto”. Both involve artists, which is typical of Browning. Andrea Del Sarto is a troubled artist while in the other poem the arrogant, boastful, egotistic, tyrannical and cruel Duke talks about a painting – a portrait of his wife (who he apparently murdered). Of great interest is the way both “My Last Duchess” and “Porphyria’s Lover” speak to contemporary issues of women as victims of domestic violence, and their place in both an aristocratic and a patriarchal society.

The woman’s vulnerable position arises out of those norms of aristocracy and male dominance with great threat coming from the possessive and obsessive nature of the male narrators in both poems.

What lends great strength to these pieces is their direct relevance to social ills both of Victorian society and the present time. Modern readers can easily see what is despicable about the cruel acts of the narrators in both poems – acts which Browning places in the context of the social climate of his environment. The two societies, though separated by time and distance, are both patriarchal, but the horror of the murder of women comes home very starkly to the present day reader because of the scourge of domestic violence wreaked against women by spouses and spurned men in today’s society. It is instructive that in the nineteenth century Browning was using art to condemn the practice, as we see in these poems.

“Porphyria’s Lover” is outstanding for the unspeakable horror of what it describes.

The narrator is possessive. For reasons which are not spelt out in the poem, he cannot have her all to himself; her personal situation, whether it be constraints of family, domestic situation or social status, means she can only visit him secretly. But his possessiveness becomes an obsession leading to the kind of mental derangement which makes him feel he has to do something to make her permanently exclusively his. He believes that by killing her at the very moment when she is demonstrating her love for him he will preserve the moment and have her all to himself without interruption.

Recognition of the problem in this action seems beyond him.

Not only does he think he has found a solution but he reasons that it is justified. This comes out in the last line. “God has not said a word” is ironic. It is true, God has said nothing – that is a fact. But both his sense of guilt and his conviction of justification come out of that silence. He knew he committed something wrong, feels guilty and expects God to rebuke him.

Added to that, are other techniques including having this happen in foul and stormy weather; the injustice of Porphyria obviously making sacrifices to visit him against the injustice of him sacrificing her without being grateful for her efforts; the lunacy of his assertion that she is now happy at being able to remain with him all night.

Yet the best part of the poem is Browning’s skilful use of irony and the narrator’s warped point of view all demonstrated in the dramatic monologue.

It is art in action; directed against a social plague.