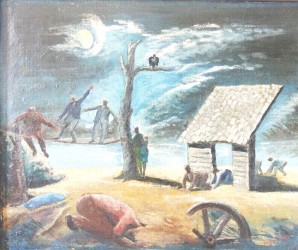

The second “Conversation on Art” between eminent Guyanese artist Stanley Greaves A A and artist Akima McPherson focuses on Edward Rupert Burrowes’s Guiana, Land of the Dolorous Garde, another significant work of art in the Guyana National Collection, housed in the National Gallery of Art, Castellani House, Georgetown.

These “Conversations” will be published on the first Sunday of every month. At the same time,

Edward Rupert Burrowes

Oil on canvas – 1951

Photo courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Castellani House

the National Gallery of Art will make the artwork available for viewing. Guiana, Land of the Dolorous Garde, which cannot be published in colour today because of constraints of space, will be on display from Monday May 4 to Saturday May 9 in the ground floor gallery of Castellani House.

Akima McPherson: In E.R Burrowes’s Guiana, Land of the Dolorous Garde four figures are on hands and knees crawling, three perform a delicate balancing act on a tight rope, one awaits opportunity to get on the tight rope, and the only one in the foreground has buried its head in the sand.

Stanley Greaves: Burrowes was actually commenting on the politics of the 1950s British Guiana, and on the universal behaviour of politicians. They put on an act balancing political rhetoric and the ideal objectives expected by a trusting public. The common man burying his head in the ground symbolises a retreat from the reality of the situation, a despairing figure. The painting presenting a scenario of total disaster was exhibited in 1951 in a Working People’s Art Class show at St Andrew’s School Hall.

AM: Considering their actions and attire – in three piece suits, I have always seen the image as a scathing critique by Burrowes of the “native” colonial subject seeking to imitate the colonial overlords from Britain.

SG: This is perhaps true taking into consideration Naipaul’s comments on the Caribbean people being “Mimic Men” having no original, ideas of their own, which created a wealth of adverse criticism.

AM: Exactly. I see Burrowes as anticipating Naipaul. I would even say the figures performing precarious balancing acts were doing so for objectives that probably went unrealised.

SG: I would disagree a bit here. If we think of politicians working primarily for their own interests, those of the country take second place. This is perhaps part of the narrative content of the satirical painting. The symbols of a neglected nation are to be found in the figures of a homeless mother and child, standing near the useless derelict shed. The broken wheel as the end of progress. The most alarming and macabre presence is that of the crow on a dead tree awaiting the demise of everyone present. While tiny figures in the background seem to be grubbing for food, those crawling from the broken shed cannot be considered proud representatives of a nation.

AM: Yes, I see what you are seeing, and the ominous sky reflects the symbolism of the crow. However, there is something people sometimes do when they find themselves at odds with their positions and situations – they assume postures grander than their realities. I felt Burrowes was commenting on this, and it is for this reason I saw the figures as representative of colonial people desperately trying to elevate themselves, through imitation. I do think this image remains relevant today. Today we attempt to elevate ourselves through mimicking imported popular culture. So instead of donning the colonial administration’s three-piece suit, many speak using Jamaican and African-American language and accent patterns, and exhibit other gestures of imitation of their perceived ideals. Interesting how we have these two very different but valid readings of the same image.

SG: Yes. This painting I would consider to be the heart/soul of the National Collection despite its small scale. The message is not only universal but in a frightening way so prophetic about the politics that accompanied the country’s independence and the ensuing years. It did leave an indelible impression on my mind from 1951 to this day. It has been the single most influential work in the development of my figurative paintings, and was certainly the inspiration for my political series There is a Meeting Here Tonight (1992-2001).