Introduction

Beginning with this brief introduction, in coming weeks I explore the linkage between initiatives to recover stolen public assets in Guyana and financing for its development. Presently, this is one of the most researched topics engaging international development agencies, governments, academics, and civil society advocates. More specifically, (as I shall explain more fully later) this is happening because worldwide, countries are preparing for the Third International Conference on Financing for Development. This is scheduled to be held next month in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. And, as designed, this conference precedes the United Nations Global Summit, expected to adopt, formally, the Sustainable Development Goals (SSGs) global agenda later in September.

Before addressing this crucial topic, I must first wrap up the deferred discussion of the situation in the rice industry. To recall, in the two previous columns I had characterized the sugar and rice industries as dangerously perched on “ticking economic time-bombs,” which threaten both the government’s public spending priorities and financing for development arising from the successful recovery of stolen public assets. I have already considered sugar from this standpoint and will only note here, for the record, government’s decision to afford GuySuCo an interim bail-out of $3.5 billion. To make-up for rice, today’s column expands on the much abbreviated comments offered so far on it.

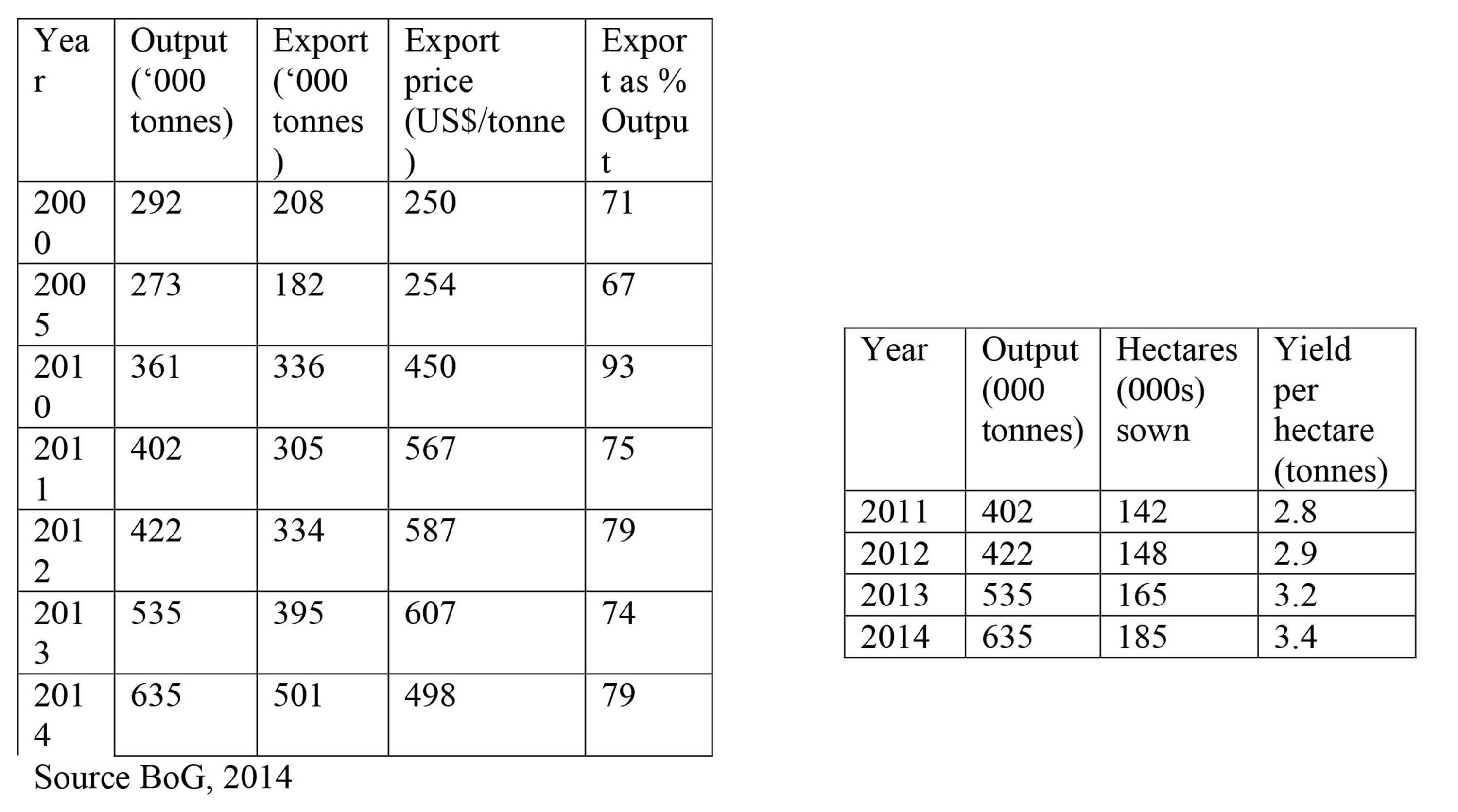

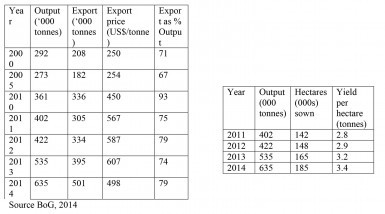

Last week I referenced the explosive growth of rice output, in stark contrast to sugar, during the 2010s. Rice output grew by more than 100,000 tonnes annually every year since 2012 and current projections show it is on track to repeat this year (see Table 1). While between 2000 and 2005 rice output fell, between 2005 and 2014 it more than doubled. Additionally, Table 1 reveals a similar explosion in rice exports. This show the crucial role lucrative external markets have played in the rice industry’s upswing. Exports account for the dominant share of Guyana’s rice sales; on average over three-quarters of production is exported. Meanwhile, global rice output during the last crop year was not only considerably larger (475 million tonnes on a milled basis) but fewer than 40 million tonnes were exported, or 9 per cent. Last week’s column hinted at Guyana’s global uncompetiveness in rice production. Table 2 reveals rice productivity (yield) has been about 3.1 tonnes per hectare in recent years. This is about one-half or less that obtained by leading global rice exporters and producers. It therefore explains the constant pressure to find lucrative overseas markets if the industry is to survive.

Table 1: Rice output and exports Table 2: Rice yields (productivity)

Success indicators and challenges

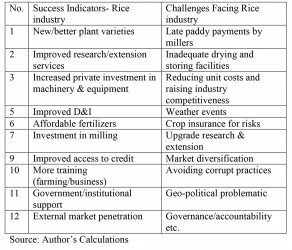

Further, I have examined recent reports, surveys, and commentaries on Guyana’s rice industry in order to identify 1) the 12 most frequently cited success indicators seemingly responsible for its recent explosive growth and 2) the 12 most problematic factors or challenges presently facing the industry. For the convenience of readers I reproduce below in Table 3 the results of this documentary examination, listed in no particular order of ranking. The success indicators include government support for R&D, extension services, drainage and irrigation, training, and finding market outlets overseas. Even in areas where private investors seemingly played the leading role (mills,

equipment and machinery) the government’s footprint is also observed. Indeed it is fair to conclude that, with the possible exception of investment in milling (which was financed in the main by local and external private investors) and machinery and equipment, the government has been the leading player by far, in the recent explosive growth of Guyana’s rice industry. The government has described its actions as “facilitation” and not “over-reaches” on behalf of its political constituents as critics claim.

However, in regard to the challenges facing rice, while capacity constraints, risk-insurance, and R&D problematics have all been acknowledged, the dominant consideration plainly lies in the area of governance. Corrupt practices, lack of accountability, non-transparency, and systemic failure of regulation and oversight are being dramatically revealed everywhere one turns. The recent mysterious disappearance of Guyana’s PetroCaribe rice fund started in 2009, shortly after a new government assumed office and immediately following my March Sunday Stabroek columns assessing PetroCaribe led to considerable public outrage. The long-standing institutional weaknesses of the Guyana Rice Development Board (GRDB) as an oversight/regulatory body are at this time legendary, and not surprisingly, repeated calls for a better composition of the board as well as forensic audits of its various activities (pricing, testing, distribution, quality control, etc) are fairly commonplace among industry stakeholders. There have been also repeated calls for free and fair elections among rice farmers to select their preferred representatives. Such governance challenges suggest that, in the midst of booming output, rice has lurched into the risk of going bust by the next crop. Like sugar this places drastic pressure on the authorities for bail-outs and undermines efforts to find financing for development.

It also, sadly, distorts priorities for public spending. This wraps up the discussion of rice for the time being.

Next week I shall continue by returning to the discussion of the linkage between recovering stolen public assets and financing for development.

Table 3: Success indicators and Challenges