Introduction

In the previous two columns, I have sought to make the case that, the major impediments, which are constraining the long-term socio-economic/environmental development, and structural transformation of the Region (and Guyana), can be effectively addressed within the framework of the United Nations (UN), Post-2015 Development Agenda and its related Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs, 2015-2030). In pursuit of this proposition, I have revealed several of these impediments; for example: 1) the long-term trajectory of low economic growth, which has been experienced in the Region (and Guyana), and 2) the lower than average rate of national savings that similarly obtains (both in the Region and Guyana), when compared to other developing regions. This has produced great reliance on a) foreign direct investment (FDI) flows, which have been rapidly declining since the Great Recession that started in 2008, and b) remittance flows from the diaspora. In turn, this has led to significant and growing inequalities in several dimensions of the Region (and Guyana’s) economic and social life; the persistence of undiversified production structures, which are heavily dependent on either tourism (and its related services) or commodities; and, the very high public indebtedness that prevails in most of the regional economies.

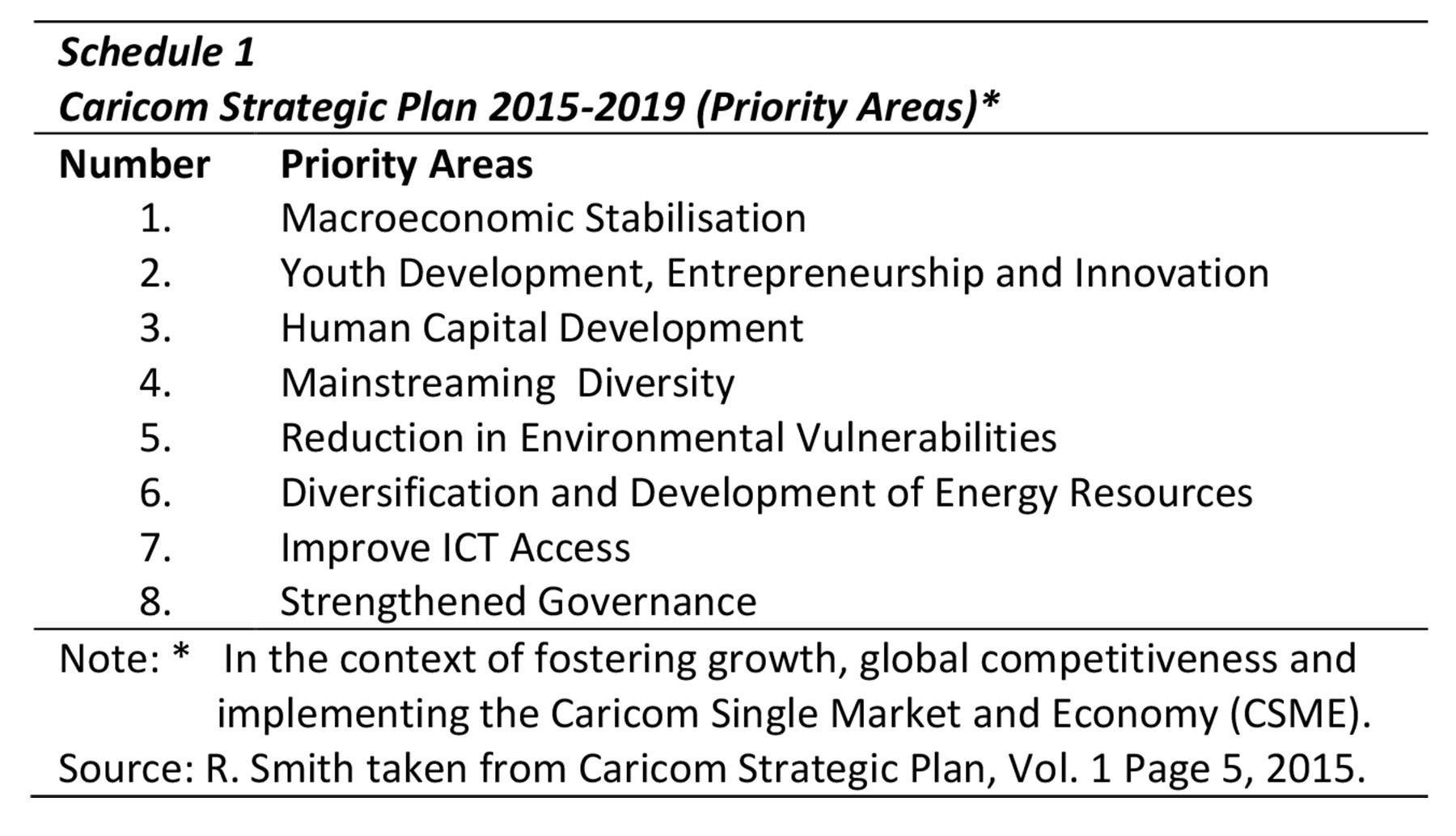

In 2014 the Caricom Secretariat had commissioned a study to evaluate and recommend to it the Region’s stance in regard to the SDGs. The final draft of that study entitled The Caribbean and the Post 2015 Sustainable Development Agenda was published in May 2015. It is authored by Ransford Smith. In the study the author has identified the main priority areas in the Caricom Strategic Plan 2015-2019. These are listed in Schedule 1. A quick inspection shows that these priority areas are fully consistent with the SDGs, as I have elaborated them in previous columns.

Those priority areas include human capital development; reduction in environmental vulnerabilities; energy resources augmentation and diversification; improved access to information and communication technology (ICT); macroeconomic stability; youth development, entrepreneurship and innovation; as well as strengthened governance. These priority areas were identified in the context of fostering growth; the Region’s global competitiveness; and the sustained implementation of the Caricom Single Market and Economy (CSME).

Although, I had previously indicated to readers my strong support for the UN’s Post-2015 Development Agenda and the SDGs, as an appropriate framework for the Region’s long-term development, it is nevertheless incumbent on me to share with readers at this moment of truth, certain concerns and reservations that remain. These fall into two categories. The first is integral to the framing of the SDGs in the Guyana context. And, the second relates to operational and implementation considerations. The first category will be discussed for the remainder of this column. And, since the latter leads in to the more detailed issues of the indicators of compliance that are used to ensure accountability in the pursuit of the SDGs, these will be addressed, starting in next week’s column.

SDGs design flaws

The first design/framing flaw readers should observe is that in Guyana the SDGs have not been widely discussed, either in the media or elsewhere. Indeed persons have recently pointed out to me that I seem to be the only person discussing these in the local media. I had not thought about my columns in this way before, but I readily concede that experience suggests, most Guyanese view the SDGs as being alien to their day-to-day lives. This is quite a remarkable state for the public at large to be at, less than a week before Guyana, along with the rest of the world, subscribes to a political declaration at the UN to put the SDGs at the forefront of all human development for the next decade and a half (2015-2030)!

I believe that the UN agencies which are resident here must share a considerable

portion of the blame for this outcome, considering that the Open Working Group (OWG) preparatory process for the SDGs has lasted for more than a year, ending only as recently as July this year.

Second, what seems to me equally regrettable is that during this time, Guyana’s lead line-ministries did not drive the momentum to ensure the SDGs form the essence of Guyana’s moving forward. They have been just as lethargic as the local UN bodies.

Third, if it is fair to blame the UN agencies and the line-ministries for this disappointing outcome after the year-long OWG process which guided the preparation of the SDGs, the non-state actors (or civil society organisations) have been equally delinquent. Such an outcome is to be deeply regretted, given the major roles that labour, faith-based bodies, academia, women’s groups, the private sector, and rights-based bodies have played in defining the long-term development agenda for Guyana.

There is little doubt, however, that in one way or another all the organisations identified above do subscribe to the view that Guyana remains very vulnerable in at least four core areas, where the SDGs apply. These are 1) integrating economic, social, racial and environmental concerns in its long-term development; 2) reducing growing inequalities; 3) promoting sustainable ways of producing livelihoods; and last, but by no means least, 4) promoting a rights-based society.

Next week I shall address the operational and implementational considerations.