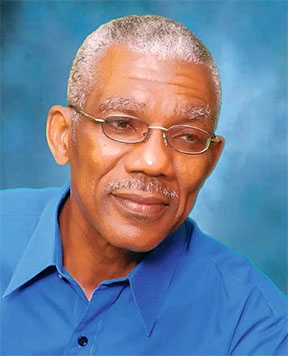

The Guyana Bar Association (GBA) yesterday questioned whether the stipulated procedures were followed by President David Granger to pardon dozens of convicts earlier this year and said that the secretive manner of the pardons is concerning and sets a dangerous precedent.

“While the Bar Association supports the principle of pardon, we regret that until these questions are answered, there can be no unqualified endorsement of the President’s action,” the GBA said in its Stabroek News column yesterday.

In May, Granger announced that he would pardon 60 persons who were sentenced for minor misdemeanors. In June, Prison Director Welton Trotz told Stabroek News that around 40 convicts had been released, a reduction of the original number proposed. He said that they have since been accepted into the USAID’s Skills and Knowledge for Youth Employment (SKYE) Project.

In its column yesterday, the GBA highlighted the pardon granted by former President Donald Ramotar, who in his last days in office, pardoned Ravindra Deo, a convicted child killer. Ramotar refused to explain the pardon and the GBA pointed out that the process was at best opaque and the action drew widespread condemnation for what was perceived as a misuse of a reserve power.

The Association also pointed out that the names, offences and sentences of the convicts pardoned by Granger and released from prison have not been publicised. “As their convictions would have been a matter of public record, it is reasonable to expect that their pardons should also be made public. While the pardoned persons may very well deserve their release from prison, utilising the presidential pardon in such a mysterious manner and without setting out specific criteria is a dangerous precedent,” the Association warned.

The GBA noted that the president has a right to pardon and in the Independence Constitution, the power – or what the Constitution referred to as the prerogative of mercy – was exercisable by the Governor General on the advice of a Minister designated by him acting in accordance with the advice of the Prime Minister. Article 188 of the 1980 Constitution contains similar provisions, except that the prerogative of mercy is now vested in the President.

Secretive

“What causes more than a little concern over the pardons by President Granger is the secretive manner of the process. As a matter of law, the publication of the names of persons who benefit from a presidential pardon is a necessary corollary to the exercise of such power. In effect, the presidential pardon is a usurpation of the judicial process and one of the few vestiges of royal prerogative inherited from our British colonisers,” the GBA asserted.

“It is anyone’s guess, in respect of the persons pardoned by President Granger, whether the stipulated procedures were followed, what criteria were used, and what type of pardon may have been given. Were any probation or other reports furnished on an Advisory Council, Minister or the President himself, prior to the granting of the pardon? And for those who have been pardoned, what conditions and systems have been put in place aimed to rehabilitate, reform or integrate them as full members of society? Will there be any increased penalty in the event that they commit similar or other offences in the future,” the Association questioned.

It said that while the GBA supports the principle of pardon, until these questions are answered, there can be no unqualified endorsement of the President’s action.

Reviewable

The Association pointed out that in some jurisdictions, the exercise of the presidential pardon is judicially reviewable in particular instances. “This is necessary where the president may have misapplied his or her powers with regards to the type of pardon granted. Each of these pardons is expected to be used appropriate to the particular situation, and will dictate, for instance, whether a pardoned person is still liable under a civil process. Wrongdoings very often give rise to simultaneous criminal and civil liability and since a right to bring a civil action is a personal right of citizens, it is hardly up to anyone, even the President, to attempt to deprive any citizen of that right,” the Association noted.

It also pointed out that while the Constitution vests the prerogative of mercy in the President, it also sets out the framework within which s/he may exercise such a power.

“Article 188 (2) provides that the powers of the President to grant pardons, respite, substituted sentence or remission of any sentence, is exercisable only after s/he has consulted with such Minister designated for this purpose. Such designation is a constitutional function and it would seem appropriate that the designation of the Minister should be gazetted as other constitutional appointments are,” the GBA said.

According to the lawyers’ body, the advantage of such consultation is that it insulates the President from any accusation that s/he has acted arbitrarily. Used judiciously, the exercise of the power to pardon can be an important element of criminal justice reform which the country so badly needs, it added.

The GBA also highlighted the other provisions of the Constitution that deals with the prerogative of mercy. “Paragraph (3) of Article 188 requires the designation of a second Minister to be consulted in cases of conviction by a court martial while Articles 189 and 190 provide for the establishment of an Advisory Council on the Prerogative of Mercy to deal with cases where persons have been sentenced to death, other than by a court martial,” it pointed out.

The GBA said that the Advisory Council must consist of the Minister designated under Article 188 (2) who shall be the Chairman, the Attorney-General if he is not the Chairman, and at least three and not more than five other persons of whom at least one must be a medical doctor.