Confidence

This article is intended to share this writer’s understanding of the Caricom Single Market and Economy (CSME) and to begin the process of considering how it could be made to work better for Guyana. It might also reveal the confidence that this writer has in the ability of the regional integration movement to survive the continual threats to its existence in the face of insufficient financial

Markets of Caricom

Where Guyana is concerned, the opportunities for economic expansion lie within the markets of Caricom and the series of open markets across the continents of the world. Beyond its borders, the countries of Caricom represent the extension of the domestic market of Guyana. It is the claim and virtue of the single market. But Guyana has not begun to penetrate the enlarged domestic market that exists in the Caribbean region that is now available under the single market regime. The lackadaisical effort in trade exposes Guyana’s failure to take advantage of what the single market means to it. This failure leaves Guyana short of expanding domestic production and employment and serves as a reminder of the wealth that is left to go a- begging. Clearly, there is an urgent need for Guyana to tap into the potential of the regional market. Guyana needs to think seriously of how it can and must serve the customers of this substantially enlarged domestic market, including dealing aggressively with any encumbrances that undermine its ability to deliver goods and services to the market effectively.

Long process

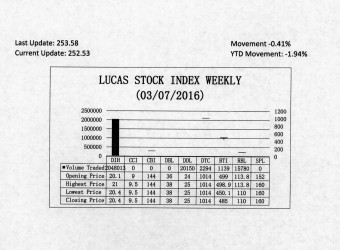

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) declined 0.41 percent during the first period of trading in March 2016. The stocks of five companies were traded with 2,087,376 shares changing hands. There were two Climbers and two Tumblers. The stocks of Banks DIH (DIH) rose 1.49 percent on the sale of 2,048,013 shares and the stocks of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) rose 4.17 on the sale of 20,150 shares. The stocks of Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (BTI) fell 2.81 percent on the sale of 1,139 shares while the stocks of Republic Bank Limited (RBL) fell 3.34 percent on the sale of 15,780 shares. In the meanwhile, the stocks of Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC) remained unchanged on the sale of 2,294 shares.

The attainment of single market status in 2006 was the culmination of a long process of economic integration that started with the conception of a free trade area (Carifta) 41 years prior to the entry into being of the single market. The single economy part of the CSME was expected to come on stream last year, but that dream has not been realized as yet. The slow march to diminished sovereignty has begun, but it will take a long time before the full diminution of sovereignty could occur.

Stiff economic challenge

According to information emanating from the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), many Caricom economies are facing stiff economic challenges. The regional economies experienced slower growth of 1.6 per cent in 2015 compared to the 2.6 per cent growth that occurred in 2014. While the experience might be mixed overall, the information before member countries suggests the need for careful and prudent management of individual economies. Interestingly, the behaviour of the economies of the Caribbean is not necessarily a direct consequence of the condition of individual economies. They do not depend on each other sufficiently for the economic conditions in one to have severe adverse effects on the other. The lack of dynamic interaction between the various economies of Caricom might be a reflection of the reluctance of member countries to take advantage of the economic opportunities presented by other regional economies.

In an attempt to come to some understanding of attitudes towards closer economic integration, it would be useful to refer briefly to the origins of the movement. With Caricom fully formed, reference is seldom made to the formation of the Caribbean Free Trade Area (Carifta), the precursor to the Caribbean Community and Common Market. The experience in forming Carifta is itself a lesson of the difficult road that regional integration has travelled. Carifta was conceived in December 1965, but was not born until May 1, 1968, almost three years after the concept was initially discussed by Barbados and Guyana. The free trade area is the lowest level of economic integration. It involves and is distinguished by essentially three characteristics. These are the elimination of tariff barriers on the goods and services produced by members of the free trade area, the retention of the right to impose non-tariff barriers on goods produced by members of the free trade area and each member retaining the right to impose its own tariff on goods that come from outside the free trade area.

The desire for the free trade area stemmed from a recognition that the economies of the Caribbean could complement each other. From its inception, regional integration accepted the theoretical arguments posited early on by Professor Clive Thomas and Dr Havelock Brewster that each country could specialize in the production of certain goods and sell them in the larger market created by the removal of tariff barriers. There was also the belief that the products of the region could become very competitive through the economies of scale that would come from large scale production.

Willingness to trust

The countries of the free trade area were only being asked to free up tariffs among themselves. They were not being asked to give up sovereignty or any power that rendered them dependent on the decision of another member state. Yet, it took four countries three years to get the ball rolling. Despite the length of time that it took to form, Carifta represented the willingness to trust each other again, especially since Carifta came on the heels of the collapse of the West Indian Federation. The format of Carifta reflected a renewed determination to bring the regional economies together. The bitterness of an aborted federation was yielding to the sweet taste of economic optimism.

Leap

The leap from a free trade area to a common market was itself an act of determination as well. The Caribbean was determined not to be left behind by unfolding economic and political events in the early 1970s. The production structure of the region was tied directly to that of the United Kingdom (UK) and the UK was about to join the European Union which at the time of its entry was called the European Economic Community (EEC). This move by the UK meant that the products that originated outside of the UK and other EEC member countries would face a common external tariff. The products from the Caribbean were about to become highly uncompetitive in what was their traditional market and faced the threat of being shut out of the market after years of dependency.

The threat to the economic survival of the Caribbean was also coming at the same time from the global finance structure. The Bretton Woods System of fixed exchange rates, which was set up after the Second World War, was about to collapse. The countries of the Caribbean were about to lose the stability in exchange rates that their currencies had enjoyed under the Bretton Woods System. Under the Bretton Woods System too, the US had made its dollar the anchor of the fixed exchange regime. The US dollar was pegged to gold and everyone else had aligned their currencies indirectly to gold through the US dollar. In the operation of the Bretton Woods System, the US had agreed to permit countries that held dollars to exchange them for gold whenever they wanted to do so. This arrangement worked well for a time and allowed the US dollar to ascend to the status of being the reserve currency of the world. But the dollar started to feel pressure after the US could not meet its short-term debts and eventually the US abandoned the fixed exchange rate system.

Means of survival

The preceding two factors of the threat of market loss and the anticipated risk of loss in value of their national currencies were powerful enough to induce Carifta countries to search for a means of

survival. They found refuge in the formation of the Caribbean Community and Common Market and its alignment with the EU. At the forefront of the Caricom initiative was the notion that trade among Caricom countries would deepen. The complementarity envisioned under Carifta never materialized in a big way. The division of labour in the production process and the lowering of prices through economies of scale that were anticipated never occurred either. Instead, member countries strengthened their trade links with their traditional markets through the establishment of a series of Protocols for their commodities under the Lomé Convention. The Lomé Convention was a collaborative arrangement between a set of African, Caribbean and Pacific (ACP) countries on the one hand, and the EU on the other, that granted products from the ACP countries preferential access to the EU market at guaranteed prices.

Tug-of-war

Some Caricom countries, especially Grenada, Guyana and Jamaica, also got entangled in economic systems that did not lend compatibility and coherence to the integration movement and may have reduced the goodwill that had been built up among Caricom countries over the years of Carifta. The tug-of-war between structuralism pursued by the three countries and liberalism followed by the rest of the region created tensions in the integration movement and threatened its survival. The experience and frustration of incongruity could have resulted in the breakup of Caricom, but it did not.

(To be continued)