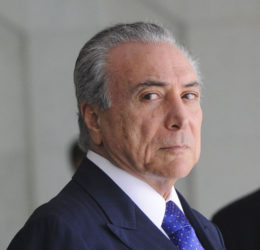

BRASILIA, (Reuters) – Corruption allegations implicating Brazilian President Michel Temer and his party are casting doubt on his ability to remain in office and causing the first cracks in his coalition amid growing calls for early elections.

Allegations that Temer and members of his inner circle solicited illegal funds for his 2014 vice presidential campaign threaten to undermine a solid majority in Congress that put him in office by impeaching leftist Dilma Rousseff in August.

Losing that majority would dismantle the two goals Temer set himself as caretaker president through 2018: to restore fiscal discipline and revive Brazil’s flailing economy.

Key allies are still with Temer, for now.

But there are signs some are ready to break ranks, and others are divided over getting burned by association with his deeply unpopular government.

Senator Ronaldo Caiado, whose Democrats Party is one of the strongest backers of Temer’s austerity measures before Congress, said this week the president lacked enough support in the country for the measures and should consider stepping down to allow elections next year.

In the centrist PSDB party, which fully backs Temer’s fiscal reform program as it eyes its own presidential bid in 2018, party leader Aecio Neves reconfirmed his support for Temer this week, as long as he sticks to the austerity agenda.

Temer is trying to strengthen his base by offering the PSDB, Brazil’s third-largest party, a fourth Cabinet post, the ministry in charge of relations with Congress.

Some coalition allies warned they may drop their support for Temer if allegations emerging from the investigation into state-run oil company Petrobras continue to involve the president. That is likely, given that the testimony of another 75 executives on Odebrecht’s massive role in Brazil’s biggest-ever graft scheme has come to light.

Odebrecht executives have already testified that the engineering firm illegally funded Temer’s 2014 vice presidential campaign. Temer has denied accepting illegal donations.

“If the president doesn’t gain credibility and the corruption investigation continues to get closer to him, then I think it will be impossible to avoid bringing the elections forward,” Senator Cristovam Buarque, whose PPS party has two ministers in Temer’s Cabinet, told Reuters.

Buarque hopes early elections can be avoided as they would mean Temer’s respected economic team, led by Finance Minister Henrique Meirelles, would exit and ignite more instability.

But the Eurasia Group political risk consultancy made the argument this week that the worries over the corruption scandal taking down leaders of the PMDB party and other allies actually benefit Temer and his austerity agenda.

“This fear will provide Temer with enough carrots and sticks to keep his coalition together and approve his reform agenda,” Eurasia said in a note to clients. “Despite growing political headwinds in Brasilia, we expect Temer to succeed in implementing most of these reforms.”

Yet Brazil’s two-year recession has shown no signs of responding to Temer’s policies and the political uncertainty continues to stall business confidence and put off investment decisions.

Discontent with rising unemployment and public anger over Temer’s first austerity measure to pass Congress, a 20-year ceiling on public spending, led to small but violent street protests that could spread in 2017 as the recession enters a third year.

Temer’s approval rating has tumbled, with 51 percent in a recent Datafolha poll finding his government “bad or terrible” compared to 31 percent in July. The poll showed 63 percent of Brazilians want new elections, more than the 61 percent that wanted Rousseff removed before her impeachment.

Congress cannot call a new election in Brazil but it can impeach and remove a president, leading to new elections.

Temer is safe from any moves to unseat him by the scandal-plagued Congress, where many politicians are besieged by corruption probes and unlikely to throw the first stone.

Rousseff’s Workers Party, dislodged from 13 years in power, is in the minority and no threat to Temer.

Yet calls for new elections might be answered from the judiciary if not the legislature.

Brazil’s top electoral court, known as the TSE, will decide next year whether or not to invalidate the winning Rousseff-Temer ticket in the 2014 vote if it is found the ticket received illegal campaign funds.

The case has gained momentum from the new evidence of kickbacks in the massive graft scheme centered on Petrobras.

The TSE justice handling it, Herman Benjamin, is expected to rule against the ticket and annul the election result, though the full court must then approve a final ruling.

On Thursday, the president told reporters he would not resign if the TSE annulled his election. Temer, a lawyer and constitutional law expert, said he would fight the decision with “appeal after appeal.”

Under Brazil’s Constitution, Congress appoints a new president if there is a vacancy in the final two years of the term, meaning that unless Temer resigns by Dec. 31, lawmakers would pick the next leader.

But Congressman Miro Teixeira of the center-left REDE Party, who proposed a bill to allow direct elections in the last two years of a presidential term, said that scenario would ignite action on the streets.

“In today’s environment of social tension, the Brazilian people would not stand for an indirect presidential election by this Congress,” he said.