Beneficiary of wealth

The global production structure is made up of an interrelated set of bargains, agreements, rules, laws and institutions that are intended to bring countries closer to each other in a more

High propensity to import

Guyana’s dependence on trade is high. Guyana has a high propensity for imported goods. Nearly as much as 70 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) depends on imports. The country’s overall ability to grow its GDP through exports is not as strong as its propensity to import. Consequently, Guyana runs a trade deficit constantly. The trade issue for a country like Guyana and other developing countries was how to achieve a trade surplus without undermining the propensity that Guyanese have for imported goods. Attempts to fix a trade deficit once recognized the sovereignty of countries and their right to develop and use policies that were in their interest. Notwithstanding the liberalist view that the trade balance does not matter and that free trade must take place at all cost, very few countries are satisfied with a perennial trade deficit. Trade deficits in and of themselves are not bad things. However, when they become chronic, they could interfere with the macroeconomic policies of a country. Here is the reason. The deficit implies that a country was importing goods on credit. In other words, it was not saving enough money to pay off for the goods and services it was buying from abroad. When that debt outstrips investment spending, the country must borrow for a longer period of time from someone else to try and pay off the short-term debt owed to its trade creditors. Sometimes even more severe measures such as devaluation of the currency are required. The hope then is to be able to export more to earn enough money over time to pay off the debt.

Overblown perspective

Such an approach works well for a country with certain production and financial characteristics. A country that sells manufactured goods is able to add higher values to its export price and eventually remove its deficit if that was its goal. Such a tactic becomes easier if the country owns a reserve or hard currency. One should be aware that countries such as the Republic of Korea and Singapore do not own hard currencies, but run trade surpluses because of the higher value-added items and services that they export. It is a credit to manufactured goods that contain high technology content, something that liberalists thought was an overblown perspective in international trade. Yet, one has to temper that reality with the recognition that a big country like the USA owns a hard currency but constantly runs a trade deficit. The division of labour in global production has other countries such as Guyana and Trinidad and Tobago producing raw materials and agricultural products. For countries that export primary commodities or agricultural products, the task is not that easy. Usually such countries do not own hard currencies and commodity prices tend to fluctuate or remain depressed because of supply and demand. Either way, perennial trade deficits can even interfere with the ego of some countries and lead their citizens to believe that restrictive trade and economic policies could help them restore lost glory.

Borrowing is not the only solution to trade deficits. Countries try to attract foreign inflows either through portfolio investments or direct foreign investments in order to have the resources to pay their trade debts. Portfolio investments, which are generally short-term in nature, usually respond to monetary stimulus such as interest rate movements or foreign exchange rate changes. They can go as quickly as they come. Countries therefore tend to rely more on direct foreign investment. It is longer lasting and, before the imposition of trade-related investment measures (TRIMS) which will be discussed later, was thought to bring several benefits with it. Foreign investment is a part of the global production structure that increasingly reflects the self-interest of the investor and his or her stakeholders. At one time, foreign investment reflected the mutual interests of foreign investor and host country. Host countries usually tried to secure employment, local content and foreign exchange benefits. In exchange, they would give up tax and tariff revenues to induce the foreign investor to come. With so many developing countries in need of foreign investment, there is competition for the limited resources of the foreign investor which enter the global production structure. Most direct foreign investment is undertaken by investors from developed countries and generally they go where there is cheap labour. But the case of Singapore and other major economies has revealed that direct foreign investment also goes where highly developed human resources exist. They go also where there are abundant resources that could be extracted at relatively low cost.

Issue of tariffs

But there was always the issue of tariffs, the part of a country’s tax structure that was often seen as a major barrier to trade. Much of the literature on the theory of foreign investment indicates that foreign investment was motivated in part also by a desire to avoid trade policies that placed their investments at a disadvantage. When home markets became saturated, firms ventured abroad to places with large internal markets in order to improve their competitive position and increase shareholder value. This practice is known as tariff jumping, and even though it offered competitive advantage given the self-interest of the foreign investor, he or she thought that the sovereign rights of the host country could place them at a disadvantage. Having avoided the tariffs, there was possible competition from local companies which were given preferential treatment by host governments.

At the same time that local producers were receiving special treatment, special demands were being made of the foreign investor. These demands included fulfilling a series of requirements. These requirements included local content requirements, manufacturing requirements, domestic sales requirements, technology transfer requirements, licensing requirements, local equity restrictions, foreign exchange restrictions and trade balancing requirements. The self-interest of the foreign investor was so strong that he or she sought various protections and benefits for the resources that came with the investment. In addition to seeking holidays from income tax payments and the waiver of import duties and other taxes, foreign investors have sought protection under the WTO from measures that they claim can restrict and distort trade, and hence their competitive position. The measures that they pursued under the international trading rules are the TRIMS.

Rules of the game

Countries that engage in foreign direct investment in a big way are interested in TRIMS. TRIMS only applies to measures that affect trade in goods. It should be emphasized here that TRIMS is not concerned with policies that regulate foreign investment nor is it concerned with what happens in the area of services. TRIMS contends that once an investor enters a foreign market as a producer, the rules of the game should be the same for both the local and foreign investors. So TRIMS focuses on the issue of national treatment and the competitive environment in the local market. TRIMS imposes a series of obligations on countries who have acceded to its principles. The TRIMS negotiated under GATT has been subsumed by the WTO and are binding on member countries.

The application of TRIMS raises a very interesting policy issue for host countries given the mechanism through which trade is transmitted. In a study published in the mid-nineties, it was noted that world trade was evenly split between intra-firm trade, inter-firm trade and trade between exporters and importers with no affiliation to each other. More recent studies seem to suggest that cross-border intra-firm trade might have gotten even larger. In a discussion in a working paper on trade policy, it was revealed that foreign affiliates in nine countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) accounted for 16 per cent of world trade. The situation in the manufacturing sector could be even more dramatic. Research has shown that for a country like Sweden intra-firm exports account for 51 per cent of total manufacturing exports.

Gains from intra-firm trade

The gains from intra-firm trade are part of the gains from investing overseas. The trouble with this is that a foreign firm comes with a guaranteed market that is not necessarily available to a domestically-owned firm in the host country. Further, an affiliate which buys plenty goods from its parent uses much foreign currency of the host country and brings little back in a trade deficit relationship. The deficit created by intra-firm trade might not require the kind of external financing associated with trade between unrelated parties, but foreign currency can leave a host country through transfer pricing. Levelling the playing field in the host country enables the foreign investors to take full advantage of a perfectly competitive resource market to the disadvantage of the domestic firm which would have given up its home-field advantage and then have to find foreign markets on its own. The foreign investor with his or her network of companies does not have to find the additional resources that a domestic producer has to find to enter a foreign market. Countries that already have a comparative advantage in intra-firm trade would see nothing wrong with the limits that TRIMS places on local producers.

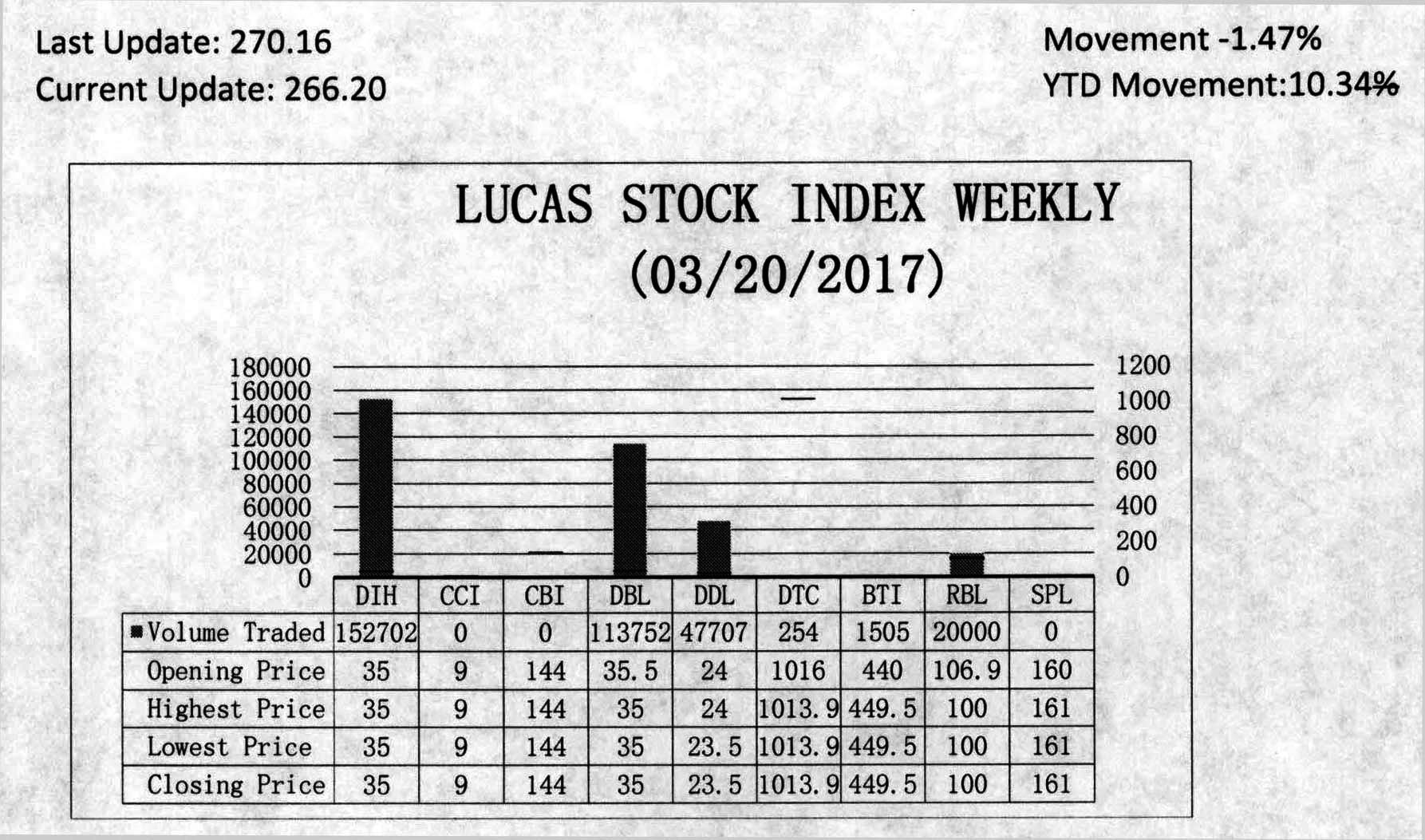

LUCAS STOCK INDEX

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) fell 1.47 percent during the third period of trading in March 2017. The stocks of six companies were traded with 335,920 shares changing hands. There was one Climber and four Tumblers. The stocks of Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (BTI) rose 2.16 percent on the sale of 1,505 shares. The stocks of Demerara Bank Limited (DBL) fell 1.41 percent on the sale of 113,752 shares while the stocks of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL) fell 2.08 percent on the sale of 47,707 shares. The stocks of Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC) fell 0.21 percent on the sale of 254 shares and the stocks of Republic Bank Limited (RBL) fell 6.45 percent on the sale of 20,000 shares. In the meanwhile, the stocks of Banks DIH (DIH) remained unchanged on the sale of 152,702 shares.