by Estherine Adams

This is the first in a series of articles which gives a brief overview of Eusi Kwayana’s involvement in national politics in British Guiana between 1950 and 1961. In this article, I propose to examine Kwayana’s rise to the national political arena, and his involvement in the original People’s Progressive Party (PPP) up to 1953. In subsequent articles, I will examine his years in the original PPP following their electoral victory in 1953, (1953-1957), and his years in the PNC, (1957-1961).

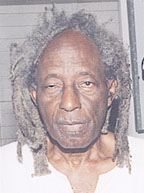

Eusi Kwayana, formerly Sydney Evanson King, who has been referred to as the ‘Sage of Buxton’, ‘Renaissance Man’, and ‘Guyana’s Gandhi’ among other titles, was born at Plantation Lusignan, East Coast Demerara, on the 4th April, 1925. He attended Lusignan Anglican School and Cumberland Methodist School. King began his teaching career as a primary school teacher at age 15 and later founded the County High School, which was renamed Republic Cooperation High School, at Buxton. A staunch believer in education, he studied privately for the Inter BA in Economics.

Although King has been active in the cultural life of the country, he was involved in politics both at the local and national levels. As a local politician, King along with Martin Stephenson organized the Buxton Rate Payers Association in 1949. This association grew into the authentic representative of the increasingly alienated villagers on all issues, and even led successful opposition to the Central Drainage Board which refused to provide proper drainage, thus precipitating six floods in the village in 1949. King also served as a village councillor and deputy village chairman of Buxton during the 1950s.

However it is in the field of national politics that King has made his most telling contribution. This was aided, by the formation of the Political Affairs Committee (PAC), the People’s Progressive Party (PPP) and the People’s National Congress. The PAC was formed in 1946 by Cheddi Jagan, Janet Jagan, Jocelyn Hubbard and Ashton Chase, with the aim of mobilizing and educating the masses for political action oriented towards achieving political independence. The Committee, which surfaced in response to the strains of the 1940s and because the existing political organizations, as Dr. Jagan put it, were ‘opportunistic and not interested in the masses’, was of critical importance during a period which the founders felt constituted the formal beginnings of the struggle for political independence.

The PAC differed from previous discussion circles because it was overtly political and sought to reproduce itself and its ideas within the body politic. Hence by the end of 1949 there were Worker Discussion Circles at Kitty Village YMCA Hall each Sunday under the chairmanship of Cheddi Jagan, and at Buxton Village Hall where the Buxton Programme Group was convened every Friday night by Sydney King. Even though King was not a founding member of the PAC, he quickly became one of the prominent members of the organization, along with Martin Carter, Ram Karran and others. They were regarded as ‘some of the most active organizers all over the country’.

The PAC was committed “to assist the growth and development of Labour and Progressive Movements of British Guiana to the end of establishing a strong, disciplined and enlightened Party, equipped with the theory of Scientific Socialism.” Furthermore, it trumpeted the idea of replacing the capitalist structure of the society with one in which the masses, through their representatives, would be permitted to participate in major decisions affecting the economy and the country as a whole. These ideas strongly impacted King, to the point where he was later described by the British and Americans as ‘extreme leftist and blindly pro-Moscow’.

King’s first mentioned exposure to national politics came in late 1947 when the first elections in British Guiana since 1935 occurred. Fourteen constituencies were contested over by numerous independents along with candidates sponsored by the League of Coloured People, the British Guiana East Indian Association, and the Man-Power Citizens Association. The PAC at that time, although still a small, relatively unimportant body, sent up three members, Cheddi Jagan, Janet Jagan, and Jocelyn Hubbard who fought the elections as independents.

Though King did not contest the election, he was the chief architect of Cheddi Jagan’s 1947 electoral campaign on the East Coast Demerara which won him a seat in the Legislative Council. Jagan stood for the East Demerara constituency and won his seat running against John D’Aguiar, a man who had had tremendous influence among the business and plantation elite and in the government. In recognizing this contribution, Jagan remarked, “One of my protégés, schoolteacher Sydney King of Buxton, was of great help to me in the villages.”

In 1950 the leaders of the PAC took the big step of forming a political party of their own, the People’s Progressive Party. The goals of the PPP as stated in the 1951 Constitution were to stimulate political consciousness along socialist lines in the quest for “national self-determination and independence” and “the eventual political union of British Guiana with other Caribbean territories.” King, elected Assistant Secretary, was prominent among the leaders of the party. The other leaders were C. Jagan (2nd Vice Chairman and House Leader), F. Burnham (Chairman), C. Wong (Senior Vice Chairman), J. Jagan (Secretary and Editor of Thunder) and B. Benn (Executive Committee Member).

As a leader of the PPP King brought experience, though of a lesser magnitude than Jagan, gained from similar involvement in existing organizations to the Party. He was by this time an experienced local authority man and was also active in the Guyana Industrial Workers Union and the British Guiana Teacher’s Association, especially along the East Coast of Demerara. The personal contacts and influence of the leaders were used to stimulate interest in the Party. King made good use of his position and reputation as a village teacher to spread the doctrines of the Party among African villagers, especially in Buxton where he was living.

During the early 1950s King had the reputation as a staunch Marxist and in his capacity as Assistant Secretary, he represented the PPP at the Congress of Peoples for Peace in Vienna in 1952. He admitted to local authorities that he brought back some $US4000 in cash upon returning from his trip to Vienna. This trip to Vienna was followed by a visit in 1953 to Budapest, where he reported on British Guiana’s social conditions and concluded with a visit to Prague. Upon his return home, he was alleged to have brought back a suitcase full of Communist propaganda, pamphlets and correspondences with Communist contacts in Eastern Europe and England.

According to Dr. Jagan, it was because of “our [the PPP’s] continuous agitation the Waddington Constitutional Commission visited British Guiana in late 1950.” Among other things the PPP’s delegation argued in favour of full self-government in presenting their evidence before the Commission.

The Commission did not accede to their demands as “it did not feel that Guiana had reached the stage for internal self-government.” To say the least the PPP was not pleased with the decisions made by the Commission and King went as far as to say that “it amounted to devilish swindles,” and launched a ‘Constitution Amendment’ campaign at Buxton.

The Commission did, however, recommend universal adult suffrage and in April 1953 the first elections under this new constitution were held. This time, King was a part of the formidable list of candidates that the PPP offered to the electorate in every constituency. The line up of rival parties was also formidable on paper but in reality none of them had been in existence as long as the PPP, and “none of them had developed any individual sense of unity of idea to be really considered politicians. They all depended on the personality appeal of their leaders.”

The PPP contested twenty-two of the twenty-four seats and King stood for the Central Demerara Constituency. He felt that his “contact with working people left him in no doubt that the Party ‘could win the election.’” The PPP, to the surprise of many, was victorious at the 1953 Elections, winning 51 per cent of the popular vote and 18 of the 24 elected seats in the House of Assembly. King won his constituency, polling 70.6 per cent of the total votes cast, indeed a resounding victory.

Signs of stress and strain were not absent at the moment of exultation, and they were focused on Burnham’s ambition to be Parliamentary leader of the party as well as chairman. This and disagreements over the distribution of ministries led to a one week crisis, “Crisis Week”, before the PPP Government could take office.

A similar situation occurred at the PPP Congress in March. Just before the election, one of Burnham’s allies moved that the leader not be elected at the Annual Congress, but be chosen by the General Council after the general election. Burnham anticipated a majority in the latter body. In the debate on the motion, King made an impassioned speech. “This is a motion of no confidence in our leader; why such a motion of no confidence in our leader; why such a motion at this time?” he asked.

Martin Carter had suggested that King be appointed leader. King refused immediately, despite Burnham’s agreement, because of bad principle. It would have meant superseding Jagan, who was by far the most senior member, and King was deeply against this idea. King moved, seconded by Westmaas, that the decision of the last Congress be implemented and the ‘Leader of the Legislative Group’ be named ‘Leader of the House’. The rank and file saw Sydney King’s point, threw out Burnham’s motion and Jagan remained leader.

The challenge posed by Burnham in “Crisis Week” was seen as a further effort on his part ‘at a rather late hour to acquire the leadership of the party’.

The ministers were selected finally, after intense discussions which very often found members in conference until well past midnight. It is of interest to mention at this stage, that, according to J. N. Singh, “the party was then rent asunder, right down the middle, with Jagan having close to him Chase and King, whilst Burnham was supported by Dr. Latchmansingh and myself [Singh].”

Those selected as ministers of the new government were Cheddi Jagan as (Leader of the House and Minister of Agriculture), Forbes Burnham (Minister of Education), J. P. Latchmansingh (Minister of Health), Ashton Chase (Minister of Labour), J. N. Singh (Minister of Local Government) and Sydney King, (Minister of Communications and Works), responsible for Public Works, Post Office (other than Post Office Savings Bank), Transport and Harbours and Civil Aviation.

Having resolved the crisis the leaders were ready for the grand opening of the legislature on 30 May 1953.