(Part 3)

By Estherine Adams

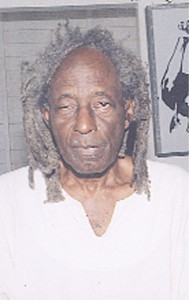

This is the final instalment in a series of articles which give a brief overview of Eusi Kwayana’s involvement in national politics in British Guiana between 1950 and 1961. In the first two articles, I examined Kwayana’s rise to the national political arena, his involvement in the original People’s Progressive Party (PPP) up to the 1953 elections and his time as a minister of the government, from May 1953 until the suspension of the constitution and the party was put out of government in October 1953, after only 133 days. In this article I will be focusing on Kwayana’s departure from the PPP, his stint in the PNC and his subsequent departure from that party.

The setback of 1953, when the PPP was put out of office, directly or indirectly led to the first split in early 1955 between the Jaganite and Burnhamite factions of the PPP. In late 1954 and early 1955 Burnham had a majority on the PPP Executive Committee since some of the Marxist leaders were in prison or restricted to areas outside Georgetown. He used his majority to call a party congress in Georgetown for February 12 and 13, 1955. The Jagans protested and after a considerable amount of public controversy, Burnham and Jagan agreed that a special conference of the party be held. At this conference, Burnham accepted a motion to suspend the standing rules, moved a motion of no confidence in the Executive Committee and, after Jagan and about 200 of his followers walked out, held elections for a new Executive Committee.

A few weeks later the Jaganite faction held a party congress, chaired by King who was still a committed Marxist and loyal to Jagan, in Buxton. At this congress the elections held in the Georgetown conference were declared null and void, and the Burnhamite faction, which included J. N. Singh and Dr. Lachmansingh, were expelled from the party, while King, Carter, Westmaas, and Chase remained with Jagan. At this time the split in the PPP was not deemed a racial split. Both leaders agreed that the reasons for the split were “ideological and tactical” differences. Thus, between 1955 and 1958 there were two PPP organizations, the PPP Burnhamite and the PPP Jaganite, as the two leaders struggled to retain the name meaning so much to the ordinary working people of British Guiana.

A second and more damaging split occurred in the PPP Jaganite in 1956. At the PPP (Jaganite) annual conference, an address written by Dr. Jagan sought to spell out (a) who was to blame for the party’s problems; (b) why this was so; and (c) what steps should be taken to remedy the situation. In his address he also criticized some of the African Marxists in the party for “ultra-left, deviationist tendencies” and for opposing the party’s stand on the West Indian Federation. Dr. Jagan pointed out that the circumstances which had resulted in the suspension of the Constitution were ascribable to a movement to the [extreme] left. Because of this, he continued, PPP members had become ‘bombastic’, and ‘were attacking everybody at the same time’ and, moreover, their actions were characterized by ‘all struggle and no unity’.

Since King, Carter and Westmaas were among those who had espoused Marxist principles, they interpreted the ‘bombastic we’ as a reference to them. This, added to the fact that Jagan had observed that ‘feeling as they do a sense of oppression the Indians are 100 per cent against Federation’, which meant that the PPP was now adopting an anti-Federation position, convinced King, Carter and Westmaas, as Africans, they had no place in the PPP. They eventually resigned from the party and politics, the first two temporarily and the last one permanently.

King, in early 1957, refused to run as a Jaganite PPP candidate in the 1957 elections and then shocked the PPP Jaganite by filing as an independent candidate. The loss of Sydney King was a serious blow to the Jaganite PPP’s multi-racial strategy. King took most of the Jaganite PPP’s remaining African support with him and left the party without a well known African leader. By the time of the election, King had the endorsement of the Burnhamite PPP and shortly after the election King joined with Burnham.

The 1957 elections were contested by the PPP Burnhamite, the PPP Jaganite, the National Labour Front, the United Democratic Party and several independent candidates, of which King was one. King contested the Central Demerara constituency, but lost to a prominent East Indian businessman, Balram Singh Rai, who was endorsed by the PPP Jaganite as King’s opponent. The PPP Jaganite won the election with nine of the fourteen seats, and Burnham conceded the PPP name to Cheddi Jagan and renamed his own group, the People’s National Congress (PNC) in October 1957.

The PNC contained a wide cross-section of Guianese: its leader was F. Burnham; its officers were J. P. Lachmansingh – Chairman; Sydney King – First Vice Chairman; F. A. DeSilva – Second Vice Chairman; J. N. Singh – General Secretary; Jessie Burnham and A. L. Jackson – Assistant Secretaries; and Stanley Hugh – Treasurer. King was also the editor of the PNC’s organ, the New Nation.

After King left the PPP, where he was labeled an extremist and a communist, his views became more black nationalist. Probably it was this change of view that led him to join the PNC in 1958 and remained with the PNC until he left one month before the 1961 elections.

Shortly after Burnham’s acceptance of King into his Party, J. N. Singh left the PNC primarily because of King’s increasing influence and set up the Guianese Independence Movement. For the 1961 elections King and some other PNC members advocated a campaign against the threat of racial domination by the East Indians and accused Jagan of attempting to replace “White supremacy with Indian supremacy.” Burnham had pointed out earlier that even if the PPP won the election he would work towards independence. King saw this as “dangerous to the African people” and proposed that there should be a “joint and equal prime ministership”, with an Afro- and Indo-Guianese as prime minister.

If this move failed, King proposed the partition of British Guiana into three parts, one for Negroes, one for Indians and one for those who ‘wish to live with other races’. The result of the position taken by King was that he was expelled from the PNC for, as was stated in the New Nation of 21 July 1961: “At an emergency meeting of the Executive Council held on July 20th, it was unanimously decided that Mr. Sydney King be expelled from the PNC for proven anti-party activities.”

The press release went on to say that: “With respect to the ground upon which Mr. King has declared his intention not to run as a candidate for the PNC, the Executive Committee declares that it is unequivocally committed to independence for British Guiana and will not swerve from its present policy which has been accepted by the Congress and the Executive Committee of the Party of which Mr. King was a part….Independence is the inalienable right of Guiana, and the PNC. Though it will always strive to protect the interests of all groups it will never stand in the way of independence regardless of the party in office.” The official PNC statement gives the impression of a party trying to set the record straight. King’s expulsion from the PNC in 1961 brought an end to his direct involvement in national politics for a short while.