The Guiana Times News Magazine 1946-1966

By Nigel Westmaas

‘Guiana Times does not sell propaganda it sells news carefully analysed and served up in a tasty way.’ (Guiana Times, May-June 1951)

In an editorial extolling the news magazine, Percy Armstrong wrote in 1951 that in its third year Guiana Times had “developed a reputation (good and bad) for virile analytical entertaining journalism. Although the rising cost of production is threatening to put us out of business yet we look back with considerable pride from the little experimental journal in 1949 to what is now the largest circulating journal of its kind in these parts… we have been trying to run a publication – perhaps unique in the world – that is a combination of a political pointer, race rag, detective magazine and general factotum…”

”]![20091220leaders [Forbes Burnham and Cheddi Jagan circa 1953]](https://s1.stabroeknews.com/images/2009/12/20091220leaders.jpg)

Content, ‘ragging’ and ‘dithyrambics’

A substantial bit of Guiana Times’ impact was derived from its garrulous and folksy representation of everyday intelligence on local politicians. Armstrong, whose editorial presence was very pervasive in the magazine, evidently had a solid ear to the ground and was an impressive political prober. With an acute political and social purview and a sense of his readership, he appeared to hold substantial, up-to-date information on his subjects of interest, especially where it centred on the internal bickering of groups like the PPP and League of Coloured Peoples )LCP) and the movements and station in life of their leading members. As Guiana Times put it, “ours is the difficult job of going back stage and seeing what the actors look like with their masks off and producing news for information sake. Thus we run the risk of antagonizing the actors and the vast patrons they attract.”

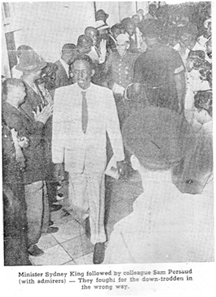

Antagonize, the magazine certainly did. A major approach of the Guiana Times was the direct ‘in your face’ depiction of Guyanese. With this predisposition to the ideology and activity in local politics no group or person (except perhaps a softer critique for local governors and the ruling elite) were exempt from Armstrong’s withering, cynical, playful and critical gaze. Regular targets included such high-profile figures as Cheddi and Janet Jagan, Forbes Burnham, Keith and Martin Carter, Jessie Burnham, Brindley Benn, Sydney King (Eusi Kwayana), Andrew Jackson, Rory Westmaas, Aubrey Fraser, Jainarine Singh, Clinton Wong, Rudy Luck, JP Lachmansingh, Jane Phillips-Gay and Claude Denbow, along with the organizations to which these folks were linked, including the PPP, the LCP and British Guiana East Indian Association (BGEIA) and assorted trade unions. Even the famed labour leader Hubert Critchlow was the object of a sarcastic critique from Guiana Times as Armstrong addressed Critchlow’s “fall from grace” in society in 1955.

The Guiana Times regularly made unsubstantiated claims, and given the nature of the publication’s drive for pugnacious news, this was not surprising. One of these claims was the contention that then (1954) education Minister Burnham had “arranged with another communist minded scholar Dr Elsa Goveia to write text books with [a] socialist bias.” Goviea strenuously rebutted the allegation in the tiny letter area allowed in the periodical. The editor in accepting the correction curved it to his editorial advantage: “thanks Dr Goveia, your letter conclusively proves that your political admirers in British Guiana talked too much about things they couldn’t do.”

On another occasion, reacting editorially to a letter chiding him for attacking Jagan and Denbow (often described in the magazine as a “rotund city dentist”), Armstrong opined, “we would like to give both Jagan and Denbow a rest but they pop into the news so often that we can’t ignore them. We do not attack them but try to reflect them as the public sees them not as they would like to see them[selves].”

While the criticisms oscillated between playfulness and downright hostility, a visible weakness in the publication’s editorial mantra was a disinclination to seek direct comment from its interlocutors. It avoided this obligation by making its own assessment of the local scene, even if it reached the point of exaggeration. The Times defended itself against the charges of bias. In response Armstrong wrote: “Guiana Times is the mouth piece of no party. Instead we function as a self appointed committee for un-Guianese (and WI) activities.” The Times did not define “un-Guianese activity” but this presumably included support for anti-colonial movements around the world, communist rhetoric and activity in British Guiana and the work of ethnic groups and associations like the LCP.

After the 1953 suspension of the constitution and the landing of British forces in the colony Armstrong could not contain his glee. In describing the scene in parliament in the aftermath of the suspension, we get a reproduction of his signature prose: “periodically Education Minister Burnham just gazed into space. His handsome face over his maroon bow-tie masked an over active brilliant brain ‘washed’ clean of diluted Marxist dithyrambics – a doctrine that actually makes the barest facts look like beastly fiction… he was gazing at the handwriting on the wall and the fan in the ceiling. Their ‘socialist’ world was crumbling on their ears.”

The portrayal of Sydney King (Eusi Kwayana) was also typical of the magazine’s prose. It repeated King’s response to his visit to Governor Alfred Savage at Government House to a huge Buxton crowd of admirers: “Savage tell me come Tuesday, Ah tell ah can’t come dat day. He say come Saturday. Ah say, ‘no ah gun fix a day.’”

For Jagan came the 1954 quip, “dentist Jagan discovered the time was opportune for his private rural dental services. This meant frequent visits to country areas with ‘dentures for downtrodden’ with propaganda cocaine for the earholes.” Jagan was a frequent target of jibes from the Guiana Times. In a testy interview in 1962 Armstrong peppered Jagan, requesting a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer to the emblematic question of the era: “Dr Jagan, are you a communist?”

Apart from its conservatism in editorial intent, that is, the ‘ragging’ of communists, the Guiana Times represented a broad span of interests and coverage. With a typical size of 40 pages per issue (it was published on average five times per calendar year), the magazine sought out and reported under headings such as ‘Imperial Affairs,’ ‘BG Affairs,’ ‘Caribbeana’ and ‘Phases of Life.’ Content included high-profile Caribbean and Guyanese murder cases reporting these court dramas all the way to the gallows; the early Federation debates; coverage of royal visits with mostly pictorial representations; failures of repatriation movements of Indians and Africans; developments in Africa, especially Ghana; Georges Giglioli and the malaria problem; profiles of Robert Adams (dramatist), Art Williams (aviator), Joycelyn Loncke (musician), George de Peana (athletics); pieces on local radio; and odds and ends on local everyday events among Guyanese (usually humorous).

Although it spent most of its time in iconoclastic mode, the Guiana Times also sent its own memorandum of observations and proposals to the British Guiana Constitution Commission in 1961.

What greatly assisted the popularity of the Guiana Times were the original shots of people and events, visitors, local politicians, governors with barbed photo captions that gave the publication its newsy character. In the year end pictorial editions (Caribia teamed with Guiana Times) veteran photographer Jimmy Hamilton was a recurrent contributor along with his famous beauty pageant photos. At the photo image level the Times was free-wheeling and open when addressing key Guyanese, and the choice of image in the magazine was fairly impartial with its display of local celebrity. Major personalities from governors to Jagan were auspiciously depicted in image and several whole page front covers were devoted to the latter.

At the high point of its circulation, the Guiana Times was available in Georgetown, Berbice, Mackenzie town, and the Essequibo, in addition to having an overseas agent. The magazine benefited from wide advertisement support comprising the main businesses of the day. Among the advertisers were Good Year, Ronson, Geddes Grant, KLM, D’Aguiar, Hercules, A&HL Kissoon, Esso, Lighthouse, Sandbach Parker, Central Garage, Wieting & Richter, Sprostons, Willems Timber, Trent House, and Bettencourt’s. Armstrong’s conservatism underlined such ties but he debunked any claims of political support from companies. Writing in 1951 he stated: “Because we love to rag anything that deserves to be ragged, they call us a rag. Others contend we are stooges of the capitalists whose favour we must court in order to get advertisements for our publications.” From all indications this well supported advertisement base was a realistic indication of at least the satisfaction, if not the political and financial support of the governor and/or the colonial office.

Race, conservatism and the Times

Criticism in the Guiana Times was not restricted to the PPP and its allies. The magazine and its editor were downright suspicious of and hostile to ethnic, religious and political groups advocating racial priorities. This did not mean that the Guiana Times advocated an objective nonracial position. Far from it. The racial stigmas of that and this era were quite visible. Magazine commentary was peppered with barely hidden contempt for the active broken English of the “coolie labourer” and his station in life. In constructing this ‘alien’ presence an active and witty reportage of local idiom and creolese ran through the news stories. In one issue, the Times repeats the words of an Indian labourer lamenting the sugar industry: “De soona dey wipe out sugar from de country de bettah… sure we gwine punish lil bit but something bound fuh happen.” This use of language was not only indicative of Armstrong’s detectable paternalism towards Indian Guianese but a confirmation of his urban abhorrence of things ‘un-English’ or ‘uncultured.’

Derisive handling of the African working class was also detectable in the magazine, and it was equally tough on African cultural and social groups. Reportage on the so-called Eze affair was a case in point. When the controversial Nigerian Prince Eze Ogueri visited the colony in 1950, the Guiana Times was suspicious from the outset. Cynicism reeking, the Times quoted in creolese an early supporter of the Eze visit, Jordanite preacher, Elder Millington (nicknamed the Conqueror): “Read de wud o gawd awe King ah come.” But the Guiana Times appeared to favour its own mention of British Guiana Governor Woolley’s comments to one of the LCP leaders: “Dr Nicholson you and the League of Coloured Peoples have been taken for a ride…” Later developments seem to bear this out.

Unsurprisingly, Armstrong’s support for conservative forces in British Guiana was noticeable. In one issue, the Times complained that the opposition was bent on tearing down the “sensible plan” on which the colonial government had embarked. Invariably, the magazine’s criticism was much softer when directed to governors and colonial policy, and Armstrong was ideologically inclined to the conservative outlook of Lionel Luckhoo and his UDF (United Democratic Front). The magazine’s latent anti-communism undoubtedly merged with an increased ethnic insecurity in the early 1960s, and extra open support for the United Force was the endgame. In the 1964 proportional representation election, Armstrong was on the United Force list and later endorsed the PNC-United Force coalition.

It is worth noting that in spite of its fierce persistent attacks on his communist and ethnically driven foes, the magazine managed to combine its unflinching anti-communism with deference for its targets, albeit mostly along class lines. The magazine’s ‘respect’ for the educated class was underlined by supporting adjectives of “brilliant,” “articulate,” “linguapotent” (as in his Burnham description) to portray its foes.

Although Armstrong might have been on the wrong side of anti-colonial events from the 1940s, in an ironical twist some of his criticisms of the PPP and coverage of splits in the nationalist movement and ideological mania of the party leadership were borne out by subsequent developments and failures in global Marxist parties and politics. His prognosis of the infighting and the alienation of a frenetic Marxism from local conditions was established in the ideological confusion and shifts in statements like those that emerged from the PPP after the death of Joseph Stalin in 1953 and the effects of the 1956 invasion of Hungary on the “starry eyed P-boys” as the PPP leaders were described.

The main hitch, despite the keen psychological portraits and criticism of the early PPP and its membership, was that the magazine downplayed or omitted any positives for the anti-colonial, pro-labour spirit of the movement. The Guiana Times’ agitated concentration on communism made it ignore or re-transcribe the efforts of the 1950s PPP to fight for things besides “communism.” In that endeavour, Armstrong failed to see past the notable naïveté of the PPP (its superficial romance with Marxism) to the more significant local colonial conditions and suffering, and largely ignored, or frowned on the party’s support of the trade union movement and the unorganized working people and unemployed. Indeed the magazine regarded local anguish as a ‘plot’ of the “Pee boys and girls.” It was likewise distrustful of Guyanese political and trade union activity unless this was associated with British colonial power.

But even while Guiana Times was ideologically cynical and pro-colonial the magazine unwittingly provided coverage to the wide range of problems faced by the colony and permitted, albeit exaggeratedly and misleadingly at times, an entrée into the day-to-day activities of personalities, parties, unions and governors. Its micro-event coverage of local politics and social life, offered then, in spite of its biases and slants, a much needed open front view seat to the inner and outer work of parties like the PPP in the 1940s and 1950s.

In the final analysis, the Guiana Times, albeit on reflection from the safe distance of the 21st century, was much more than a ‘rag.’ In spite of its controversial forays and missteps along the way, the news magazine was and is a valuable democratic repository of a contrarian social and political history of British Guiana.