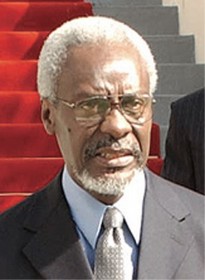

It is erroneous to pretend or attempt to portray the notion that the West Indies Cricket Board (WICB) has accepted and is proceeding in accordance with the Report submitted by Sir Alister McIntyre, Dr. Ian McDonald and myself.

The proper litmus test must measure the qualitative changes which have been approved and not the proportion of recommendations which have been accepted in order to determine whether or not the raison d’etre for commissioning the Report has been satisfied.

I challenge anyone to point out a single iota or even the semblance of change which has been made to the composition and structure of the WICB as a result of our Report.

At the very outset, it is necessary to remind everyone that the Report was commissioned to address how to improve the governance of West Indian cricket:

“to consider the composition and structure of the WICB and to make recommendations which will improve its overall operations, governance effectiveness, team performance and strengthen its credibility and public support.”

From the start, we accepted that such a mandate required us to undertake a review of all

aspects of West Indian cricket in order to recommend the best governance, remove it from the doldrums and restore its pristine glory.

We took seriously our orders to consult with administrators, players, cricketing organizations and the general public. Our recommendations emanated from the oral and written submissions we received. They were the outcome of accumulated experience, previous and current studies blended with expert advice on sound management practices.

Our sole motivation was to return West Indian cricket to the pinnacle within a reasonable time frame and thereafter to maintain the region’s ascendancy in the game.

We were forewarned, in the light of previous reports which lay buried, that our efforts would bear no fruit. Little did we realize that decisions on the most vital aspects would be taken, kept secret for a considerable period and then eventually obscured under the guise that approximately 47 of our 65 recommendations had been approved.

None of us was so beset with the sin of arrogance to believe that recommendations in our Report were “edicts or directives”, but we dared to hope that the “strong suggestions” we made, grounded on a process of full consultation, would have merited careful and serious consideration in charting the path for the early recovery and future growth of West Indian cricket.

Contrary to our expectations, we were never afforded the courtesy or the opportunity to meet with the Full Board for a discussion of the Report and to clarify, or explain, if necessary, any portion of our Report. Indeed, we learnt for the very first time in November last year, that the Board without any reference to the acknowledged stakeholders in W.I. cricket, had decided at its meeting of February 2008 to reject completely our recommendations to alter the composition of the Board and the method of its appointment.

To put it plainly, our recommendation to provide the Board with the competence to cover the entire range of its responsibilities and to make room for the specialist skills which were admitted, was torpedoed from the very start by the persons who insisted on maintaining their positions at all costs.

When the Executive Committee of the Board exposed us to the charade of a meeting in St. Lucia, it had already been decided but was never disclosed to us then “that it would not serve to strengthen the management of West Indies Cricket by reducing the number of Territorial Directors from two to one.”

We remain of the view that two Territorial Representatives from each Board result in a lopsided dominance in the governing structure. This cannot be justified as the six Cricket Boards are not the sole owners or investors in West Indian cricket.

To whomever we spoke and from every written response, there was one common thread – the game and the environment today are vastly different from 1927 when the WICB was established to promote the regional and international development of West Indies cricket. The background and imperative for change were most lucidly but succinctly conveyed in a memorandum submitted to us by Professor Hilary Beckles:

“It is now universally accepted that there is a clear relationship between the structure, design, operational culture, and knowledge content of the WICB, and the crisis of player performance that has led to the regional and international reduction of prestige West Indies formerly enjoyed.

What is now evident is that the WICB is incapable of finding by itself the answers to critical questions being posed about the future of West Indies cricket. It is evident that it should now include a wider body of skills and competence. That is, a more diverse professional skills set, and greater opportunity for all stakeholders to bring their interests to the table, is necessary in order to sustain the game as Caribbean popular culture and the global business enterprise it has become.

“The urgency of this matter is to be found in the realization that West Indian people have made their greatest single cultural investment in cricket. They have also attached to cricket their finest hopes and aspirations in the struggle to distance themselves from an ancient, debilitating colonial scaffold. This investment has yielded a priceless, public asset and its preservation should be seen as the peoples’ business. The public good, and the vision of the WICB, should therefore be seen as one and the same.

“Cutting edge international strategies that are sustaining the competitive game in other cultures have by-passed the vista of the WICB. There is palpable strategic deficiency that can only be remedied by a restructuring that brings to its deliberations the widest and most potent knowledge base the region can muster. The quality of strategic planning now required demands that the WICB be also inhabited by a more relevant professional mindset, sensitive to sustaining player-centredness, but cognizant of the wider interests that support the game.”

The Board in its own current Strategic Plan enumerates a number of deficiencies which accord with those contained in our Report:

Outdated governance structure slow and ineffectual decision-making precedence of parochial as opposed to regional interests weak communication between the Secretariat and the Territorial Boards

Excessive Board involvement to the point of micro-management.

In the face of this, how can the Board contend that the present structure remain unaltered and intact? The maintenance of the extant composition and systems of operation is clearly not an option. The rejection of any change will only serve to stultify our progress and is not a tenable proposition.

Our report asserts that West Indies cricket belongs to the people of the West Indies and not to the WICB. The Board now accepts that they are “the legal custodians of that great regional endeavour.” How will these Trustees be appointed to discharge their duties and account to the numerous stakeholders for whom they hold West Indies cricket in trust?

We examined several models and concluded that a two-tiered structure was required with separate but well defined functions in order to ensure transparency and accountability.

Once again, and after a long and thorough discussion we were fortified in our construct by the proposal from Sir Hilary:

“Without being too cumbersome, the base of West Indies cricket management must be broadened and the quality intensified, As a project it should be placed in the hands of two regional bodies; a General Council, made up of the stakeholders of the game, and an Executive Board answerable to the General Council.

General Council:

“A representative body of 15-18 persons comprised of stakeholders such as former players, CARICOM, tourism, private sector/finance/marketing/ investment, higher education, media, and arts/culture. The Council should meet once/twice a year with responsibility for strategic planning and general oversight. The General Council should have a Chairman, a person of considerable regional respect and prestige.

Executive Cricket Board:

“There should be a Board of no more than 10 members, (ex-officios not included), answerable to the General Council. Formal reporting structures should be established to ensure that this is done in a predictable manner. The Board, led by a President, should be smaller than at present, with territorial representation, and responsible for the general operations of West Indies cricket. It should be supported as at present by a professional management team.

The President of the Board should be selected by the General Council, either from within its ranks or from without, but by an open process of application and scientific assessment.”

No one could have put the case more convincingly.

It is as plain as day. The status quo is unacceptable. If there is absolutely no change in the structure and the method by which persons are chosen for a Board which is manifestly dysfunctional, there will be no change in performance. We will continue to lurch from one crisis to another; to defeat after defeat, so long as the present structure remains with the fatal flaws that now exist.

The two-tiered system was designed to provide for adequate representation and involvement, not only of shareholders, but also of substantial stakeholders. These stakeholders include Governments which have provided substantial financial capital; the Territorial Boards; past and present players who are an invaluable asset; the business community who invest and sponsor the game; tourism interests; the media; and tertiary institutions. The West Indian people, who have made their greatest single cultural investment in cricket, should have a voice.

We assigned roles in the Council for our youth and women, whose interests and skills in the game we must encourage and promote.

What we have seeks to create a participatory framework in which all stakeholders are involved and could contribute meaningfully and should not be perceived as a new bureaucratic level. As to the Secretariat, nothing but a complete transformation will suffice as the executive arm in our machinery.

The Council would meet once a year to review the state of West Indies cricket, to settle the framework and approve broad strategies for the game, to receive the Annual Report and to elect certain members of the Board.

The Board will continue to be the Executive Arm, responsible for the proper management and development of all aspects of the game. It would be expected to accumulate the material fortunes for the development of the game and authorized to conduct all negotiations on behalf of Cricket West Indies.

Our recommendation for the Board was based on the need for specialist knowledge in major aspects of the Board’s operations in areas such as marketing, finance, human resources development, public relations and law.

The West Indies is the only Test team which extends beyond national frontiers and provision for regional inputs from CARICOM and its relevant organs is critical to its effective governance.

The representation we proposed for both Bodies reflected in our best judgement the stakeholders which ought to be involved at the different levels. If the Board had any concerns about their jurisdiction, the size of the Council and the cost to service its operations, good faith and commonsense would dictate a discussion rather than a rejection out of hand.

If it is true, as Professor Beckles suggests, that a non-cricket agenda has come to surround the Patterson Report, that is most unfortunate. Certainly in the Report itself, and in our presentations thereafter, we have been careful to avoid personalizing any issue or bringing cricket politics of any sort into consideration. We were careful in this regard, since we were quite aware that the importation of any such issues into the debate would vitiate the value of our findings and reduce the potential impact of our recommendations designed solely to strengthen the structure of West Indies Cricket, revitalize its administration, finance and team-building and in general improve the prospects of West Indies Cricket with a view to bringing us again to the summit of world cricket.

If, subsequent to our Report, non-cricket issues have entered into deliberations and the taking of decisions and have indeed scuttled some of the Report’s recommendations that would fill us with dismay and should alarm the people of the West Indies to whom Cricket belongs. In such an event it would be very important to identify exactly which recommendations have been scuttled by this unfortunate development.

We quote from the joint Submission made by Barbados:

“The Board as it is presently structured and constituted, has stumbled from one crisis to another, suffers from a high level of arrogance and incompetence and continues to be a high profile source of embarrassment to West Indian Governments, cricketers and people.

“It is clear that there is a clamant need for a change in the composition, vision, mission and strategic direction of the Board if the present rapid decline in the governance, management and operation of West Indies cricket is to be arrested.”

If the credibility of the Board is to be restored and in order to mobilize greater levels of public support, basic reforms are inescapable. Tinkering will not suffice, but even that the Board has not pretended to do.

We were told last November of the Board’s intention to convene a gathering of stakeholders in March 2009. Our Report had envisaged such a meeting long before then, so as to permit the new structure to be placed before it and thereby permit whatever new structure that Conference approved to have become operational by May 2008.

While the Board is fiddling, West Indies cricket is sinking. After being beaten by Bangladesh in two Tests and the One-Day Matches, how much further can we fall?

We deliberately refrain from making any comments at this time on the impasse which has developed between the Board and WIPA so as not to exacerbate the already difficult assignment which Sir Shridath Ramphal has been requested to undertake. We must, however, reiterate that the difficult issues affecting the negotiations of players rights, intellectual property, marketing and finance, which together with many others are all mentioned in our Report, combine to make the case for far-reaching changes in the structure of West Indies Cricket compelling and irrefutable. Our cricket will not improve unless the management of the Board is expanded and strengthened.

In his urgent article, Professor Beckles states that our Report has not been disregarded. It is conceded that a number of the Report’s recommendations coincide with those of the Board’s Cricket Strategic Plan. Insofar this is so, that is all to the good. That, however, does not affect the inescapable conclusion that the pith of our Report, as to governance, has been totally rejected and leaves untouched the kernel of a structure which even the present Board admits to be outdated, unwieldy and inadequate.

Moreover, the matter cannot rest with an affirmative view by the Board of how our Report has been received. Unfortunately, there is all the difference in the world between agreeing objectives and implementing action, between the announcement of good intentions and generating solutions to problems.

It is nearly two years since we submitted our Report. It would be useful not merely to say what has been agreed but to identify exactly what has been implemented since then.

Progress can only be made when a way is found to connect the sphere of good intentions and the sphere of practical results. We intended that our Report should urgently enter the sphere of practical results. It is yet to do so.