Rawle Lucas is a Guyanese-born Certified Public Accountant and Assistant Vice-President of the Lending Services Division.

Mr. Lucas has agreed to serve as a columnist with the Stabroek Business and will be contributing articles on economic, financial and development matters.

By Rawle Lucas

Drilling

On April 20, 2010, an oil well under the Gulf of Mexico operated by British Petroleum burst open, releasing thousands of barrels of oil into the sea and killing 11 workers in the process. The oil spill is the worst in US territorial waters, bigger than the Exxon Valdez spill of 1989. The resulting political chaos, whether over wasted oil or a damaged environment, underscores this chemical’s central role in the modern world. Try as we might to mitigate its negative effects, we literally cannot live without oil, since so many common fuels and materials require oil to produce, and oil powers and lubricates the machinery that produces most of the world’s food output. Guyana is on the verge of experiencing deep-water drilling for oil with two exploration companies set to begin work by year’s end. The experience in the Gulf of Mexico makes one wonder if Guyana is prepared for any such catastrophe and if its environmental policies contain preventive measures that take account of such eventualities.

But what if the oil were to stop coming? Guyana understands the consequences of not having ready access to oil supplies. Oil makes up over 35 percent of its import bill and consumes about 20 percent of its national income. Despite the large expenditure, the country experiences unreliable power supply, disruptions in production and an inconsistent distribution network that lead to a high cost of living. The chorus against oil and other fossil fuels has grown louder with the BP oil spill and the coal mining disaster in West Virginia. If the imminent explorations proved successful, Guyana would be on the path to easing its economic problems while adding to the world supply of oil at a time when there are growing concerns about oil’s sustainability and impact as a fuel source.

Peak Oil

The concern here is about “peak oil.” Current scientific theory holds that all existing oil formed from dead plankton and algae that settled at the bottom of bodies of water, cut off from oxygen. Over the course of millions of years, sediment buried the dead organisms further into the earth, subjecting them to extremely high temperatures and pressures. This is why oil is called a “fossil fuel” (it is essentially fossilized plankton) and “nonrenewable” (the process takes very long to occur.) Thus, the oil can, in fact, run out.

That such a thing could occur within this century is not far-fetched at all. Emerging markets like India and China grow richer by the day, increasing the demand for cars and the gasoline needed to run them. Though birthrates have fallen with continued urbanization, the populations of most of these countries continue to grow. Beyond cars, Third World prosperity will give rise to demand for goods containing plastic. Travel to and from those countries would consume jet fuel. Even with increases in efficiency and use of renewables, oil consumption in all its forms would continue to increase – and some of that would be caused by the need to maintain the inevitable solar panels and wind farms that would be erected when one society or another wants to go green.

OPEC

However, calculating existing reserves isn’t as cut-and-dried as checking how much milk is left in the fridge. Oil supply depends not only on how much oil is estimated to be in a given well, but if currently available technology can recover those reserves at a reasonable price. Additionally, unconventional sources like oil shale and tar sands increase possible reserves beyond what in available in conventional wells. To make matters worse, oil-producing countries such as the member states of OPEC have incentives to hide specific information about their oil wells, preferring instead to release generalized, aggregated figures about production and estimated reserves.

Popular Image

Forget the popular image of oil wells as massive subterranean oceans that corporations stick gigantic mechanical straws into to suck out thousands of gallons of black gold. Oil exists in drops trapped within a bed of porous rock. Oil cannot simply be “vacuumed” out; the driller must apply pressure to the rock underneath via water or gas to get more oil after all the natural pressure had been released. The time when natural pressure must give way to artificially-induced pressure is hard to judge, since one cannot directly see how much oil there is underground, as is predicting when any one well would dry out. This, along with the aforementioned unreliable statistics, only makes peak oil predictions that much more uncertain. Due to this increasing difficulty in recovering oil, any given well need not become empty before peaking; all that must happen is that the cost of extracting the oil must become greater than the profit that can be earned from it.

Too Expensive

When the world oil supply finally peaks, we will not notice it right away; the price of oil will just rise as it always has. However, it will become clear that the oil has become much too expensive, driving up the price of everything that requires oil to produce. One would think that with a stratospheric increase in oil prices, alternatives like solar and wind would become viable, allowing countries to transition to those. As for plastics, a country would be able to transition to some other material that was formerly more expensive. However, while solar and wind can power a home or a small town, they are not capable of powering vehicles yet. Modes of travel that we take for granted, such as airplanes, ships, and motor vehicles, would not be usable, catastrophically impacting the global economy.

Inoperable

Also, solar and wind themselves require oil, not only to produce the components, but to transport them to where they are needed. The awesome tractors that plow the modern farm would be inoperable, and alternative fuel sources just wouldn’t be able to pick up the load with our current technology. More than anything, the breakdown in transportation could doom the global economy; the internet, for all its speed, cannot transport matter. This is often viewed as a worst-case scenario since improved technology, whether from power generation, oil extraction, or vehicle design, could mitigate the challenges that expensive oil would bring.

That being said, many people consider the world to be close to the point of peak oil, but estimates vary wildly. Some, like German Green Party MP Hans-Josef Fell, claim that the peak already occurred in 2006, while others, like Simmons & Company International CEO Matthew Simmons, claim that a peak may have occurred in 2005, but due to uncertainties over stated reserves, more investigation is necessary. Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA) predicts a 2030 peak. Further complicating matters is the idea that peak oil would not end in disaster (due to biofuels becoming more cost-effective), espoused by Chevron Chief Technology Officer Don Paul. But CERA, in spite of its 2030 prediction, does not see oil having a single peak; instead, they assert that oil production will follow an “undulating plateau” before drawing down slowly, giving the world economy enough time to adjust without catastrophic disruption.

Optimism

In conclusion, it is too difficult for a layman to judge how close we are to peak oil or even if it would matter in the long term. Everything from uncountable reserves to corporate competition to changing technology will keep any predictions from being truly accurate, meaning that no economy should bet on it quite yet. Even with that optimism, Guyana should hope that the exploration for oil onshore and offshore bears fruit since Guyanese deserve a break from their economic shackles.

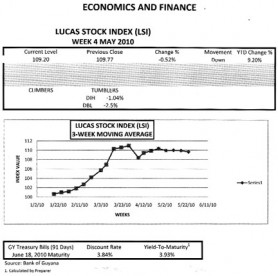

LUCAS STOCK INDEX

In week four of May, the Lucas Stock Index (LSI) experienced a further decline by half of one percent. Trading continued to be relatively light during the period of assessment with the share of three companies exchanging hands. The stocks of DIH and DBL showed declined while the price of all other stocks remained unchanged. Consequently, the LSI declined for a second straight week, placing the index at 9.2 percent. Notwithstanding the decline, the LSI remains in positive territory for the year and significantly above the yield on the risk-free Treasuries that will mature in June 2010.