This Office is supposed to be the edifice of accountability and the watchdog of the public interest. It is, according to its website, committed to the promotion of good governance including openness, transparency and improved public accountability through:

● The execution of high quality audits of the public accounts, entities and projects assigned by the Audit Act.

● Timely reporting of the results to the legislature and ultimately the public.

● Ensuring that the independence, integrity and objectivity of the Audit Office are recognised.

Its performance however, suggests that it has consistently failed to achieve its goals, even as if falls short of the standards required of the audit profession in matters of independence, conflict of interest, and capacity. As a constitutional office, its expenditure is a direct charge on the Consolidated Fund, theoretically free from any political direction or influence. To enable parliamentary oversight of the Office, the Audit Act 2004 requires that the budget of the Office be submitted for review and subsequent endorsement by the Public Accounts Committee, a Committee of the National Assembly.

This requirement is routinely ignored by Mr. Deodat Sharma who has been acting as Auditor General for several years, but who on account of his lack of any professional qualification, cannot be confirmed in the position. Instead the Audit Office deals direct with the Ministry of Finance which can thereby determine the extent and scope of the work which the Audit Office can undertake. This places the PAC in the position in that whatever it may subsequently direct or comment on in terms of deliverables and/or shortfalls in targets, may well prove to be unachievable.

Nor should the neglect and/or failure to appoint an appropriately qualified person to the position of Auditor General be regarded as a mere human resource management issue. That is a key constitutional office and the failure to have a substantive appointee is reported to affect all other consequential senior appointments – so that for the past six years at least, no one has been confirmed. Among these candidates are prospective retirees who would remain ineligible for the quantum of superannuation to which they would otherwise be entitled.

As a result, the Audit Office is perhaps the most under-resourced entity in the country. The position of the Auditor General is listed as vacant and filled by an acting appointee. Of twelve managers, nine of the positions are filled by acting appointees, or are vacant. With little attention ever paid to government accounting, this is dangerously expensive.

Like the Minister of Finance, the Audit Office routinely fails to meet deadlines set in the law for the completion of critical functions. Under the Fiscal Management and Accountability Act 2003, the report on the consolidated financial statements and the accounts of the budget agencies must be submitted to the Speaker of the National Assembly within nine months of the financial year. On the presentation of the very late 2007 report in June 2009, Mr. Sharma assured the Speaker that the auditing of accounts for 2008 had already commenced and that the report thereon would be submitted to the National Assembly by December last year. That has come and gone, even as the Auditor General (ag.) announces, presumably seriously, that his Office would be doing a value-for-money (VFM) audit of purchases.

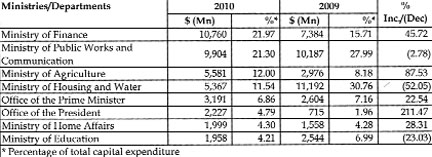

In early 2009, the Audit Office with assistance from the Office of the Auditor General of Newfoundland and Labrador of Canada undertook a VFM audit it was of the Palms Geriatric Institution. A VFM audit is really an investigation into whether proper arrangements have been made for securing economy, efficiency, and effectiveness in the use of resources. The choice of the under-resourced Palms was hardly a suitable candidate for such an audit. But it was a soft target and distracted attention from the heavy discretionary expenditure incurred, without authority or oversight, by the Office of the President and other budget agencies.

The Audit Office impresses not only by its failure to carry out some of its functions within the statutorily prescribed time, but also its abject failure to carry out others. For example, the law requires the Auditor General, or some suitably qualified person designated by him for the purpose, to carry out annually, a procedural or process audit of incentives granted under section 2 of the Income Tax (In Aid of Industry) Act. None has ever been done. That was the same section that the Government hurriedly amended to facilitate concessions to a politically connected business house.

In 2008, the Minister of Finance announced that work would commence on the strengthening of the Audit Office’s capability in performance audit, forensic audit and audit quality assurance. The reality is that the Audit Office now barely has the resources to do very basic auditing in a timely manner. The development of these capabilities require expertise and experience and a culture and approach to auditing that have so far not been demonstrated by the Office. It will not achieve those by rhetoric or overnight.

The final issue is this: even if the Audit Office had the will, it does not have the capacity. Of an approved strength of two hundred and twenty-three, up to very recently there just over one hundred positions filled, with another thirty recently appointed. With most of the higher positions unfilled or occupied with unqualified persons, the Audit Office simply does not have the capacity to carry out its principal mandate and meet its statutory deadlines. This must be a cause for major concern to anyone wishing to address the almost daily occurrences of financial improprieties, involving several hundreds of millions.