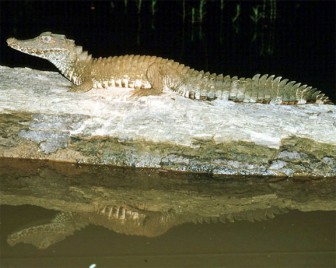

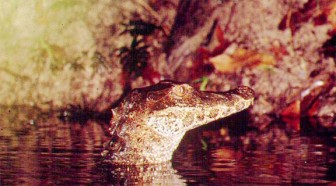

Four species of caiman exist in Guyana: the Black Caiman, Spectacled Caiman and two species of dwarf caiman. Alligators do not occur naturally in Guyana! The two species of Dwarf Caiman that are found in Guyana are Cuvier’s Smooth Front Caiman (Paleosuchus palpebrosus) and Schneider’s Dwarf Caiman (Paleosuchus trigonatus). Both species prefer cooler waters than other crocodilian species and they lack the ridge nestled between their eyes like the Spectacled Caiman and Black Caiman, hence they are called “smooth front” caimans. Their range includes the Amazon Basin of Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, French Guiana, Guyana, Paraguay, Peru, Surinam and Venezuela. Cuviers and Schneiders inhabit clear, clean fast moving waters with waterfalls and rapids, are known to be terrestrial and may frequently be seen resting along the edge of water bodies.

While these species may look similar there are subtle differences in their behaviour and morphology. Like their other crocodilian relatives the species are sexually dimorphic. Cuvier’s Caiman is the smallest of the crocodilian species with the males growing to about 1.3 – 1.5m while the females grow to 1.2 m. Cuvier’s Caiman retains the reddish brown body colour it hatches with; its back is mostly plain and nearly black while the upper and bottom jaws are covered with several dark and light spots. The tail has encircling bands to the tip. This caiman has more bony plates than any other species and its scale characteristics allow it to de differentiated from other crocodilians.

Schneider’s Caiman is bigger and the second smallest crocodilian overall. The males typically grow to lengths ranging from 1.7 to 2.3m, while the females generally peak at 1.4m. Schneider’s Caiman hatches with a golden patch on the head that disappears as it ages. The species become more bony and ridged as it gets older and the scutes are very large and sharp allowing for better protection. The tail is short and heavily ossified making it inflexible. The snout of this species is more pointed and it is believed that combined with the stiff tail the species is well adapted for swimming in fast currents.

The two species are known to breed late in the dry season with the hatchlings emerging with the rains filling in the creeks and streams. More is know about the mating of Cuvier’s Caiman than Schneider’s Caiman. Cuvier’s Caiman has a complex mating ritual. The male breeds with multiple females and prefers mating at night in shallow water. Both male and female may build the nest. Like most crocodilians they are mound nesters. The female may lay 10 – 25 eggs which hatch in 90 days. She will stay protecting the nest until the eggs hatch and stay with the hatchling for several weeks. The hatchlings will stay in the nest for several days until the female digs them out. The species reaches sexual maturity depending on size as it correlates with age. Males can reach maturity at 1.1 m and females at 1 m. It may take more than 10 years to reach maturity.

For Schneider’s Caiman it is known that the males are territorial and will chase rivals out of their territory. They do not use mating calling to locate females. The females may lay between 10 – 20 eggs which take over 100 days to hatch, longer than any other crocodilian. It is known that they prefer to build their nest near termite mounds taking advantage of the heat that is generated but is not necessary to incubate the eggs. Schneider’s Caiman reach sexual maturity at 1.4 m for males and 1.3 m for females. This may correspond to ages between 10 – 20 years.

Of the two species, Schneider’s Caiman is the less social species. It is usually solitary unless congregating for breeding.

Cuvier’s Caiman is more social being found either singly, in pairs or groups. In groups, there is a dominance hierarchy for Cuvier’s Caiman. The most hostile and aggressive individual is in charge; controlling access to mates, nesting sites, food and living space. Dominance is assorted not by physical fights but by social signals and posturing.

For both species there are dietary stages. Hatchlings feed mainly on shoreline and aquatic insects and other arthropods. Juveniles’ diets include insects, but also more vertebrates including fish, birds, amphibians and reptiles. The adult Cuvier’s Caiman increases its intake of fish, birds, reptiles, small mammals and aquatic invertebrate.

Schneider’s Caiman, because its rigid tail makes it difficult to hunt in open waters, spends more time hunting in the forest. Both species are quite opportunistic, eating whatever they can capture.

Both species of Dwarf Caiman are listed as Lower Risk or Least Concern by the IUCN Red list. Trade of these species are permissible and they are, therefore, listed as Appendix II under CITES. The risk to these two species, however, will increase due to habitat destruction and gold mining.

Rain forests are rich in biodiversity and are home to many different plants and animals as well as indigenous communities. Even if you don’t live in the rain forest, humans rely on the forest for resources such as building materials (wood and lianas), medicine and fruits. Rain forests also provide essential environmental services for life on earth; they create soil as well as prevent soil erosion, produce oxygen though photosynthesis, maintain clean water systems, and are a key defence against climate change.

The Iwokrama Rain Forest is 371,000 hectares, located in the heart of Guyana. Our mission is to develop strategies for conservation and sustainable development for local people in Guyana and the world at large. We are involved in timber, tourism and training. Come and visit us in the rain forest or at http://www.iwokrama.org.