By Nigel Westmaas

Nigel Westmaas teaches at Hamilton College

“When sorrows come, they come not single spies, but in battalions”

Hamlet

The recourse to libel against a vocal columnist is also indicative of the levels to which the fear of the spoken and written word has reached. But let us place the libel case in context. Libel suits in themselves are a normal form of protection of a citizen from a newspaper and other print media. The history of libel suits in Guyana is long and deep and dates back to when the newspaper press was founded in 1793 under Dutch colonial rule. However, what distinguishes libel against an individual by a representative of the state in this instance, is the general environment in which the right to sue for libel is exerted. The judiciary and constitution under which the libel case is being prosecuted are frayed and broken. While sparks of courage and judicial integrity remain, the entire system is besieged; the interference with judicial appointments and the attrition of personnel from all sections of government not least of all in the legal system and diplomatic personnel, tells its own story.

The list of transgressions against the media is long and includes such interventions as cutting of state advertisements to media houses deemed hostile to the regime, and restrictions on radio and television access.

Meanwhile, the Wikileaks exposures that continue to unfold with embarrassing speed reveal things about events, people and consequences that were already known; things unknown that are now in public purview; and even newer, previously unknown levels of depravity – the likes of which Guyana has never seen. And there is more to come.

In all this, the overwhelming deficit in national life in Guyana stands as a backdrop and witness to the new outpourings of excess, the cause of which resides, to restate the importance of the location, in the state of our political culture. But how did it come to all this?

Not all the deterioration in the social and political fabric of the country can be laid at the door of the current administration. They have only succeeded in accelerating what has been brewing now for a generation – or from back when things were considered “stable.”

In spite of the admitted horrors of colonial rule there was a degree of stability and social steadiness in the overall social and political conditions. This found representation in institutions as varied as the structure of a professional civil service, the management of cricket clubs, school administration, urban transport, management of polders, village administration, among other facets of society. In point of fact, without sanctifying colonialism and its excess and restrictions on freedom of locals (and we should note here that positive developments in the condition of colonial society were not only an act of the colonists), many areas of life were vastly superior to the present chaos and instability in Guyana’s current polity. This social stability continued into the immediate post-independence period and was noticeable in areas like the maintenance of streets, public works, civic organisations, and the upholding of literary, artistic and citizen values. When the late Guyanese artist/activist Brian Rodway was studying in Czechoslovakia in the 1960s, he showed off a copy of an annual Guyanese report of the Department of Local Government. The Czechs were impressed enough to remark: “you belong to a developed country”. That civil service professionalism, efficiency and other traditionally “stable” platforms have dramatically declined and imploded over time to bring Guyana to its existing state.

Today, when queries are directed at the state about the democratic deficit it has brought on the nation for the last twenty years, we get the response of “development” in the evidence of “progress” in big buildings, huge hotels, bridges, and new commercial banks. This is a cynical and deceptive response because the continued exodus from Guyana, the horrific rise in corruption with the advent of the PPP/C into government, the tight control they exert on the national media, and the degraded state of our political culture remain the more significant counter narrative than material signposts of advertised “development.”

The reverence for physical “development” rather than a national embracing response that also integrates psychological and political aspects of a country’s progress is not new, whether in Guyana or abroad. Perhaps the fondness in citing traditional assessments of GDP (Gross Domestic Product), HDI (Human Development Index), and other economic, political and social evaluations as indicators of a country’s progress has necessary merit. But these indicators are clueless about the sometimes intangible nature of the political culture in a given country. Thus, when the reality of “progress” in human terms does not change substantially in decades and in fact worsens, alternative ways of seeing and doing are imperative. The “non-material” portion of a nation’s “health” does not lend itself to easy evaluation but has its origins in the nature of the political culture and national psyche of a country.

Because of a flaky recourse to nationalism, many are afraid to call out the reality. Guyana is a rundown, desperate place where there is little solidarity in the political framework and in social and civic culture; and where the shifting sand of emigration and the intolerance of an elected autocracy continually restrict a positive political culture from emerging.

The term political culture itself is admittedly vague. In general it refers to civic and political attitudes and behaviour in society at any given time (and over time). Habitually the nature and mediation of political culture is closely tied with the constitutional apparatus and economic and social state of the country. In Guyana, a “new” forward looking political culture would have to engage the major crises the country faces. But “present time” politics and social life for the average Guyanese (including political activists) is now overly concerned and consumed with survival. Survival comes in many forms – an unrelenting search for greener pastures anywhere but Guyana; the everyday hustle on the streets to survive, and cynicism.

Overall, there is a kind of national exhaustion with struggle and confrontation and at all levels and consequently the general response to corruption and excess of office is relatively subdued. So much so now that when individuals and groups try to protest publicly on the streets it is seen as an aberration or extremist by the state and its supporters

What is patently clear is all previous attempts at single party rule have failed and that irrespective of the importance of “democratic elections,” the country needs a period of national refection and motivation. It will not be easy and it can only come with more respect for a crucial component of any new political culture, namely criticism.

Criticism (and its ally “self-criticism”) is a necessity for development. Indeed Eusi Kwayana, one of the more self-critical figures in Guyana’s political history, in his booklet Bauxite Strike And The Old Politics, made a stirring plea for the importance of criticism in and of political parties at a time when he was becoming increasingly distant from and critical of the actions of the then PNC government. What he wrote then is incisive advice for all political parties, past and present: “A party that cannot stand up to mild criticism and benefit from it is blowing short. A party that is in Government and cannot accept and offer moral challenges is in a state of decay.”

The testy and visionless receptivity to criticism is profoundly lacking in the revelations that pour forth from the libel case against Frederick Kissoon and from the Wikileaks cables. It is indicative of the depths to which this country has plunged. Given the psychological gravity of the crisis and the drastic slippage in all modes of society it would also be rational to urge that the time for common action to stop the national embarrassment is now. The alternative, we might reasonably conclude, given our recent past and dashed expectations, is that all hope has been extinguished or “gone ah falls.”

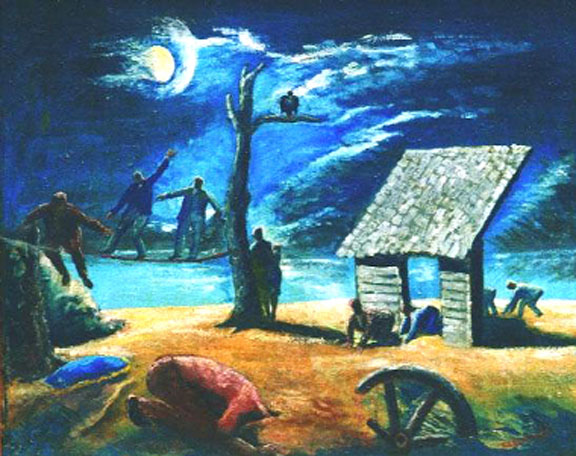

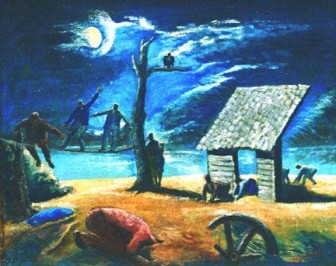

The painting Land of the Dolorous Guard stands as a powerful and moving description of Guyana. It is moving because it represents the “past” (1960s) and is still very much a painting of the present. In his book The Art of Stanley Greaves, Rupert Roopnaraine describes in vivid terms the outline of this famous work of art of Guyanese painter E. R Burrowes:

“ a waste land of ruination under an angry blue- black sky; scudding clouds, a full moon, and a stretch of stagnant water reflecting the sky. Next to the water’s edge, the remnant of a building reduced to a sloping roof, a supporting wall with a doorway through which figures scramble simian like on hands and knees, following the leader.”

That was Guyana’s past. It is also very much the present. Will it be its future?