BRASILIA (Reuters) – Brazil’s support for a United Nations human rights investigation on Iran confirms an important shift in foreign policy emphasis under new President Dilma Rousseff and paves the way for closer US ties.

Latin America’s dominant power is keeping its independent foreign policy, likely resulting in continued tensions with Washington over prickly issues such as trade and representation in international institutions.

But Thursday’s UN vote signals that the two nations are now more attuned on giving weight to human rights in foreign policy and are unlikely to repeat last year’s chilling of relations over Brazil’s friendly approach to Iran. Since taking office on Jan 1, she has stressed that the defence of human rights would be a major part of her government.

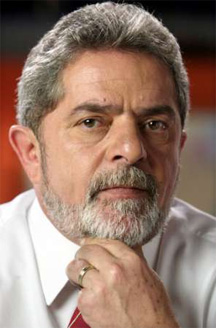

Previous President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva led a diplomatic campaign in his last year or so in office to mediate on Iran’s nuclear programme, angering Washington and other Western powers.

The charismatic former union boss played down reported rights abuses in Iran, once comparing protesters after disputed 2009 elections to disgruntled soccer fans. Brazil, the world’s fourth-biggest democracy, has in recent years aligned itself with one-party states such as China and Cuba in UN votes in order to protect governments accused of rights abuses.

Rousseff, a former left-wing activist who was imprisoned and tortured during Brazil’s 1964-1985 military rule, made it clear soon after being sworn in on Jan 1 that changing Brazil’s stance on human rights was a priority.

Soon after her October election, she broke with the political outlook of her mentor Lula, and criticized Brazil’s earlier abstentions in UN resolutions on Iran’s human rights record.

“The position is not designed to please the United States as some are saying, it’s the result of the president’s personal convictions on human rights,” said Rubens Barbosa, former Brazilian ambassador to the United States. Rousseff, who last week met US President Barack Obama during his trip to the region, has also signalled a broader shift in foreign policy toward warmer ties with Washington, which Lula regularly blamed for a host of global ills.

The UN vote consolidates the warming of ties and could even shore up support for Brazil’s bid to obtain a permanent seat on the UN Security Council. Obama effusively praised Brazil’s role as a key global player last week but fell short of endorsing that ambition.

China strains

On Friday, all of Brazil’s major newspapers splashed news of the Rousseff administration’s vote on Iran on their front pages. “Dilma turns her back on Lula’s buddy,” read the headline of Correio Braziliense, the capital’s main daily newspaper.

Brazil’s new stress on human rights risks cooling relations with its top trade partner China, one of the seven countries alongside Cuba and Russia that voted against the rights probe. Brazil’s ties with China, which Rousseff will visit for a summit of top emerging economies in April, have become strained in recent months by growing complaints by Brazilian manufacturers over a flood of cheap Chinese imports. Latin America’s largest economy, which has cast itself as a leader of the developing world on issues such as trade and the environment, has by no means become an unconditional US ally.

Brazil refused to back a UN resolution authorizing the use of force in Libya, ahead of strikes on the North African country that awakened old concerns across Latin America about Washington’s use of its military power.

Only hours after Air Force One left Rio de Janeiro for Chile, Brazil called for a ceasefire in Libya and UN-backed dialogue to end the violence there.

“Certainly this vote will facilitate dialogue and rebuild confidence with Washington,” said Julia Sweig, Director for Latin America Studies at the Washington-based Council on Foreign Relations.

“But I don’t think Brazil will suddenly abandon its independent foreign policy.”