NIMBA-BUCHANAN RAILWAY, Liberia, (Reuters) – In the muggy forest of central Liberia, a gang of workers is inching its way along a railway track, cut long and straight through an otherwise impenetrable mesh of trees and vines. The drone of insects is interrupted by a high-pitched drill and the clang of hammers as workers put the finishing touches to the perfectly aligned steel tracks.

Casting a watchful eye over the crew of workers is Lewis C. Dogar, a veteran of Liberia’s railway. Dogar and a handful of colleagues have been brought out of retirement to help reclaim hundreds of kilometres of track from the jungle. The softly spoken 64-year-old remembers Liberia’s booming 1960s and 1970s, when trains laden with iron ore wound south from the mine on the mist-shrouded Mount Nimba to the sweaty port town of Buchanan. That finished with the outbreak of fighting, and two back-to-back civil wars that lasted 14 years. The conflict, which finally ended in 2003, left more than 200,000 people dead and Liberia’s finances and infrastructure in ruins.

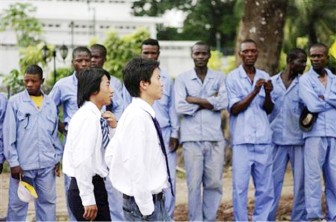

The gang of Liberian railway workers is a small sign things may finally be improving. Some of the men have only recently swapped their weapons for blue overalls and yellow hard hats. “We have a few young boys coming out of high school,” Dogar says. “I am happy that I am around to train people.”

Hiring locals might seem unremarkable on a continent with an oversupply of cheap labour. But the issue of who works on Africa’s big infrastructure projects has come into sharp focus in recent years. At building sites from Angola to Zambia, teams of Chinese workers often do the work instead of Africans. Where locals are employed, their rough treatment by Chinese managers has stirred bitterness. In Zambia last October, the Chinese managers of Collum Mine shot and wounded 11 local coal miners protesting over pay and working conditions.

That growing resentment is one reason why Brazilian engineering group Odebrecht, contracted to get Liberia’s railway rolling again, made a conscious decision to employ locals for the job — and treated them well.

“It worked perfectly,” says project manager Pedro Paulo Tosca, who decided to divide the 240 km (149 miles) of track into sections and assign dozens of separate villages along the way to clear them. “The majority of the heavy work was activities that we could perform with local manpower instead of bringing sophisticated equipment to the site.”

Odebrecht’s initiative is not solely altruistic, of course. The unlisted company sees big profits in Africa. But as it pushes into the continent, Odebrecht and other Brazilian firms are using every chance they have to keep up with their Chinese rivals, who often enjoy a massive financing advantage thanks to the deep pockets of Beijing, and who rarely pay much attention to factors like human rights.

As investment in Africa grows — foreign direct investment surged to just under $59 billion in 2009 from around $10 billion at the turn of the century, according to UNCTAD, the U.N.’s agency that monitors global trade — so too do the expectations of host nations, who want not just trade, roads and bridges, but also jobs and training. Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, World Bank managing director and a former finance minister in Nigeria, told one of China’s biggest mining conferences in November that investors in Africa need to work with local communities to avoid conflicts and start building the real economy rather than just stripping resources. If it can build a reputation for doing just that, Brazil thinks, it might help it stay in the game.

“If (Brazil) wants to distinguish itself from the other emerging powers, it needs to demonstrate what is different about its engagement with Africa based on the principles it espouses as a democratic country,” says Sanusha Naidu, research director of the China/Emerging Powers in Africa Programme at Fahamu, a Cape Town-based organisation that promotes human rights and social justice. “It will also have to reconcile its economic ambitions in Africa with its posture of being a democracy, especially in cases where it does business with essentially corrupt and malevolent regimes in Africa.”

“BETTER THAN NOTHING”

Odebrecht’s decision to employ people who live along the track is clearly popular. After seven years of peace, Liberia’s economy is only slowly getting back on its feet. In Buchanan, the port, small businesses are feeding off the rebirth of the railway, winning contracts to clean offices, transport material or put food on the plates of workers. Though accurate figures are hard to come by, Liberia’s unemployment rate is believed to top 80 percent. Such is the hunger for jobs that a number of the new railway workers have come from the capital, Monrovia, hundreds of miles away.

As you head north towards the mines the only real signs of development are the rubber-tapping collection points in the clearings that pepper the thick green forest. President Ellen Johnson-Sirleaf may have stabilised the nation but she faces re-election later this year and is struggling to convince people the economy is on the mend. Odebrecht’s 2007 decision to employ 3,000 villagers was a significant boost.

“We are happy with what we are earning… Something is better than nothing,” says Abraham Browne, a village contractor, between scooping mountains of rice into his mouth during a lunch break. Browne has swapped subsistence farming for a daily wage of about $4.50 for hammering nails into the tracks: “It helps us send our brothers and sisters to school because some of our parents are dead, killed in the war. It helps us a lot.”

Odebrecht asked each community along the track to select a leader, with whom the Brazilian firm then signed a contract. The company has completed more than 75 percent of the work with Liberian labour, says manager Tosca. It has also trained up teams of engineers, technicians and accountants to help run its offices. The first iron ore, from a mine run by Luxembourg-based ArcelorMittal, is due in mid-2011.

In terms of cost, the decision to hire locally “is cheaper because labour here is not expensive,” says Tosca. “Of course, you have a learning curve. The risk of accidents is higher — therefore you have to invest more time in training. (But with machines), if you have a breakdown, to have a part here, to replace it, takes several weeks, if not months.”

Tosca says the company believes it has an obligation to help the local economy, which in turn helps the company. “You create loyalty. They wear the shirt of the company. It is (a) kind of chemistry,” he says.

Former human rights activist Kofi Woods, now Liberia’s minister for public works, says Brazil is an “important partner” in developing the country.

A QUESTION OF ATTITUDE

Brazil is working that message hard. Former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who stepped down in January, spent a good part of his eight years in power selling Brazil as Africa’s partner and highlighting the ways in which Brazil is built on the “work, sweat and blood of Africans” shipped across the Atlantic during the slave trade. Lula visited 25 African nations, doubled the number of Brazilian embassies in Africa and boosted trade to $26 billion in 2008 from $3.1 billion in 2000.

Gilberto Carvalho, chief of staff for Dilma Rousseff, Lula’s hand-picked successor who won a presidential run-off late last year, told Reuters that Africa will remain a top priority, not just for the new team but for Lula too. The former president has long said he would like to some further, but as yet unspecified, role on the continent.

Brazilians seeking to do business in Africa are quick to play up the cultural ties between the two places: dishes based on palm oil, beans, okra and cashew nuts, the African religions that live on across Brazil, the fact that almost 90 million Brazilians have African roots. Inevitably, football player Pele helps bring down barriers among Africans passionate about the game, Brazilians say. “Brazilians are well-received in these countries,” says a Brazilian diplomat serving in West Africa. “We are a mixed country. We have cultures from lots of countries. We were a colony, so people see us as equals. They don’t see us as a power that comes to colonise.”

Adriana de Queiroz, Executive Coordinator at the Brazilian Center for International Rela-tions, a think tank, says that attitude helps. “We are going there to form partnerships and to build up our companies,” de Queiroz says. “Petrobras, for example, is not going to Africa to bring back oil to Brazil. It is to grow the company in other markets. China is not there for this reason. They are there to extract resources.”

While China is increasingly keen to emphasise non-resource related projects, like helping countries set up special economic zones to boost local industries, the differences have not gone unnoticed in Africa.

Mthuli Ncube, chief economist and vice president of the African Development Bank (AfDB) Group says conditions that some African nations agreed with China have, in effect, created “a barrier to employment creation” as China imports its own labour. Brazil, on the other hand, has gone beyond commercial ties to include social programmes and alliances with African countries. “Brazil’s value of accountability when engaging with African nations is bearing importance, especially when compared to China and its ‘no strings attached policy’ that some African governments are increasingly finding offensive.”

THE FINANCE GAME

When it comes to sheer numbers, though, Brazil still lags a long way behind. China’s agile, state-backed policies have pushed Beijing’s trade with Africa to $107 billion a year. India too, has boosted links: India-Africa trade is about $32 billion a year. That puts Brazil, with $20 billion in trade in 2010 (it slipped after the credit crunch), in third place. Rounding out the BRIC economies, Russia trails a distant fourth, with just $3.5 billion in 2009, according to IMF data.

Brazil’s weak points are many. Start with financing. China has long enjoyed links with Africa, but the bonds have deepened since 2000, when Beijing embarked on a series of resource-backed deals in which Africa handed over oil, bauxite, iron ore and copper and cobalt in return for dams, power plants and other infrastructure projects worth billions of dollars. Chinese firms enjoy a plethora of financing opportunities from institutions like the China Exim Bank, the Bank of China and the China Development Bank. Sweeping in behind these deals, Chinese businesses — from small street traders to mid-sized companies dealing in everything from construction materials to hotels — have set up shop across the continent.

Brazilian firms looking to invest in Africa can tap BNDES, Brazil’s national development bank, for financing, while Banco do Brasil, Latin America’s largest bank by assets and Brazil’s biggest state-run bank, announced expansion plans last August to exploit growing demand for loans and other products in Africa. But that still leaves Brazil Inc. well behind its Chinese counterparts. “BNDES plays an important role but it is limited by the conditions that prohibit it from financing in more unstable markets,” says Sergio Foldes, international director at the bank, which has about $2 billion in projects in Africa.

That’s one reason for the huge gap between China and Brazil’s performance in Africa. Frontier Advisory, a South African-based consultancy, estimates the number of Chinese firms operating in Africa rose to 2,000 in 2008 from 800 in 2006. Those companies range from resource and construction firms to textile manufacturers and telecommunications companies. Brazilian companies, on the other hand, tend to be traditional resource firms like Vale and Petrobras and are concentrated in a handful of countries: Angola, where Odebrecht has been active for more than 25 years, Egypt, Mozambique, Nigeria and South Africa.

Investment levels also tell the tale. By 2007, cumulative Chinese foreign direct investment in Africa had reached $13.5 billion, or 14 percent of all Chinese FDI, Frontier Advisory said. Brazilian FDI in Africa between 2001 and 2008 added up to just $1.12 billion, according to the Brazilian Central Bank. “Brazilian resource and construction firms … do not offer such comprehensive packages,” says Hannah Edinger, senior manager and head of research at Frontier Advisory.

The Brazilian Center for International Relations’ Adriana de Queiroz concedes that the gap in support for Brazilian business remains large. “Brazil isn’t in a position to compete with the (Chinese) model because we can’t even get close to the volume of financing,” she says. “We don’t have the resources for that.”

Indeed, Chinese foreign exchange reserves at $2.85 trillion dwarf Brazil’s $298 billion. “Our government is not going to fund projects in countries where there is a high level of risk,” says de Queiroz. “Chinese capital, in contrast, has a greater appetite for risk.”

Brazil knows it has to be more aggressive in financing, says Brazil’s former foreign trade secretary Welmer Barral. “The Chinese are very aggressive in finance so we are trying to empower our capacity to finance different projects in Africa, especially in construction services.”

A MINE IN GABON

But as one experience in the tiny central African nation of Gabon seems to show, it’s not just finance where China is more aggressive.

The rich but technically challenging iron ore concession of Belinga had been ignored by the international mining community for years when it came under scrutiny about six years ago thanks to rocketing iron ore prices. Gabon’s then-president Omar Bongo had long used the country’s oil wealth to buy social peace, largely by allowing rampant corruption among his allies and co-opting and coercing the opposition. But Gabon’s oil reserves were dwindling and Bongo saw a chance to cash in on another hot commodity.

In March 2005, Brazilian miner Vale secured an exploration contract and began work on feasibility studies for an iron ore mine — a complex undertaking due to environmental concerns. Before Vale was done with its study, a Chinese joint venture called CMEC came in promising to complete the job more quickly and throw in a hydro-electric plant, a railway and deep water port. When the Brazilians said they were unable to complete the project as quickly, it was handed to the Chinese.

Local media swiftly reported that corruption had helped in the decision, though both Chinese and Gabonese officials denied the allegation. “There was never irrefutable proof that this happened but I heard that money had changed hands,” says a western diplomat who was serving in Gabon at the time. The diplomat says a number of cabinet ministers had been seeking to take advantage of the ageing president to cut deals behind his back on the project: “The problem was that Bongo had not been included in the deal.”

In 2007, according to Brazil’s Folha de S. Paulo newspaper, quoting leaked U.S. diplomatic cables, senior Vale officials pointed to the Gabon incident in warnings to the U.S. ambassador in Brazil that China’s growing influence in Africa threatened international markets.

In the end, amid warnings from Chinese engineers that the project was indeed more complicated and expensive than they had previously claimed, a row broke out over plans to build a dam on a protected waterfall. The collapse of commodity prices during the global crisis, and Bongo’s death in 2009 sealed the mining project’s demise. Ali Bongo, the late president’s son and successor, has called for a review and there is talk of bringing the Brazilians back onboard.

For listed companies like Vale “there are constraints on corporate misconduct. However, in the longer term, Brazilian companies may see this as a competitive advantage in terms of differentiating themselves from other emerging market players. Why compete with the Chinese on that level (of corruption)? It is better to keep their powder dry and wait for the Chinese to fall at the technical level,” says Chris Melville, senior associate at political risk consultancy Menas Associates. “Unlike their Chinese competitors, Brazilian firms spend a lot of time and effort seeking to align their interests with those of their hosts — not just governments, but broader economic and social interests. They’re still motivated by making profits, of course, but they recognise that aligned interests are the key to long-term and sustainable profit-making.”

HELP ON THE FARM

So what, besides jobs and sweet talk, can Brazil offer Africa?

“For Brazilian companies to compete with Chinese companies, it is necessary for them to offer more transfer of technology and more local employment,” says Renato Flores, an analyst at Fundacao Getulio Vargas, a Brazilian think-tank.

Flores sees Brazil’s greatest potential in agriculture. Over the last 30 years, Brazil has reversed its status as an importer of foodstuffs to become a leading producer of soybeans, sugar, coffee, oranges, poultry and beef. It is a world expert in bio-fuels. Agricultural exports are around $75 billion a year and the industry contributes about six percent of Brazil’s GDP.

Almost three-quarters of Africans still rely on the land for their work, but most farms are subsistence level. The continent missed the Green Revolution that transformed India and China and has battled recurrent food shortages. The U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates Africa needs $11 billion in agriculture investment a year to feed its growing population.

But change is happening. Corporations, investment funds and other nations with little land see vast potential in a continent which uses less than a quarter of its 500 million hectares of arable land. After years of neglect, African governments have pledged to devote at least 10 percent of budgets to agriculture and set themselves the goal of making the continent a net exporter of agricultural products by 2015.

To unlock its potential, Africa needs to revamp its infrastructure, introduce large-scale mechanisation and improve varieties and yields.

That’s where Brazil comes in. Brazil is already making its research available to various African nations to give their agricultural sectors a boost. In 2008, the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation EMBRAPA set up shop in Ghana, for instance. Brazilian scientists began working on everything from growing and processing tropical fruit and vegetables to producing meat, managing forests and, significantly, developing agri-energy.

“One of the expectations is that what we have done in terms of our tropical agriculture could be replicated in Africa,” says Antonio Prado, coordinator for international technical cooperation at EMBRAPA. “There are similarities in soil, climate and temperatures.”

For now, as in other sectors, real financial muscle is lacking. At the moment, according to Prado, Brazil’s government spends just $17 million or so a year on agricultural cooperation projects in Africa. In 2009, China loaned a single country — Angola — $1 billion to rebuild its farming sector, crippled by years of fighting.

But that doesn’t mean Brazil is irrelevant.

“What they are very much trying to do is use their comparative advantage in a few fields,” Willem Janssen, an agricultural specialist at the World Bank, adding that relationships, for now, appeared to be based on knowledge, rather than money. “You can do that if you believe you have a lot of knowledge or not a lot of money. It is probably a bit of both,” he added.

However sweetly Brazil talks, though, there is potential for friction. Brazil’s biofuel industry is growing fast. It’s already a leading producer of sugarcane ethanol for cars. The country is also the world’s sixth largest manufacturer of cars, the vast majority of them with flex-fuel engines that can run on both petrol and sugarcane ethanol.

As part of its broader push to compete with China, Brazil wants to secure a position as a global provider of ethanol. To do that, it will need a lot of land.

“We are transferring a lot of knowledge and technology about biofuels to many African countries, on one hand because we believe it is a way to create wealth locally that is an alternative for many of these countries,” said Barral, Brazil’s former trade secretary. “On the other hand to create a world market for biofuels, we need more partners, we need more producers.”

But while supporters of biofuel crops say they will help fight climate change and generate badly needed power and income, critics say they will take food out of hungry mouths by turning arable land over to fuel crops, stoking tension with local communities.

A study by Friends of the Earth last August said biofuel demand was driving a new “land grab” in Africa. There have been protests following land acquisitions by foreign companies in Tanzania, Madagascar and Ghana; tensions are also mounting in Sierra Leone. If Brazilian biofuel producers push aggressively into Africa the potential for conflict will grow.

Back in Liberia, Lewis C. Dogar ponders life during his country’s civil war. Women were raped, children trained as soldiers, resources plundered.

“It is a story I don’t even want to think about,” he says, as he recalls the way he had used homemade carts known as “makeaways” to transport goods from village to village along the track. “(There were) no brakes. You just looked up to the Lord and (told) him ‘I am coming home.’“