Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind?

Should auld acquaintance be forgot, and auld lang syne?

Chorus : For auld lang syne, my jo, for auld lang syne

We’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet, for auld lang syne.

And surely ye’ll be your pint-stowp! and surely I’ll be mine!

And we’ll tak a cup o’ kindness yet, for auld lang syne.

We twa hae run about the braes, and pu’d the gowans fine;

But we’ve wander’d mony a weary fit, sin auld lang syne

We twa haed paidl’d I’ the burn, frae morning sun till dine;

But seas between us braid hae roar’d sin auld lang syne.

And there’s a hand my trusty fiere ! And gie’s a hand o’ thine!

And we’ll tak a right gude-willy waught for auld lang syne.

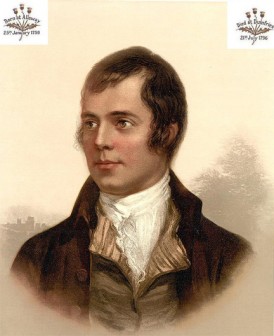

Various versions of those words would have resounded all across the world last night, since the song Auld Lang Syne by Robert Burns has become the international anthem for the New Year and is sung or played everywhere on the stroke of twelve on Old Year’s Night. But how did a mere light-hearted poem in praise of drink achieve such prominence as the most celebrated and popular verse of its kind in the world? There is more to it than that.

Robert Burns (1759-1796) published several folk songs and bawdy lyrics about carousing, sexuality and drinking, which he himself described as “the simple and the wild.” These include Coming Through The Rye, about a sexual encounter in the field of rye, which has a ‘printable’ and an ‘uncensored’ version (found in Wikipedia) with explicit words to shock and react to his critics. John Barleycorn: A Ballad (1782) is a tribute to whisky based on an old folk song and tells of the Three Wise Men bringing the gift of whisky to mankind. Scotch Drink (1786) is an ode to scotch whisky, the poet’s muse, and Lady Onlie Honest Lucky (1787) is one of countless folk drinking verses.

Poems of this nature are found even among his more serious work. “Tam o’ Shanter” (1792), for example, is a humorous ‘heroic’ satirical commentary about drinking which also takes a dig at the church, but it includes dangers and horrors, a touch of folklore and a warning against excessive drink.

His core of strong poetic work is by no means voluminous for a major national poet, and his achievements in this regard are relatively limited. But Burns is very highly regarded among British writers; he is the greatest Scottish poet, the National Poet of Scotland where he is known as ‘The Bard’; is described by literary critic David Daiches as “the greatest song writer that Britain has produced”; is extremely popular and influential worldwide, including in Russia; and is commemorated in statues and monuments in several countries including the UK, Canada and the USA. He worked as a farmer and a ploughman for most of his life before the rapid success of his published poetry shifted his focus.

To what does he owe this extraordinary reputation? First, to the quality of his verses; to cite a few of his best known and most acclaimed poems, To A Mouse (1785), A Red Red Rose (1794), Scots Wha Hae (1793), The Battle of Sheramuir, Tam o’Shanter and Auld Lang Syne contain examples of this quality in some memorable lines, depth of meaning, profound imagery, neatness of metre and structure. These lines have influenced and inspired other writers. American John Steinbeck’s novel Of Mice And Men (1937) took its title from the lines “The best laid schemes o’ mice an’ men / Gang aft agley.” This is a well-known idiomatic saying, now common in the English language and rendered as “the best laid plans of mice and men go oft astray.” JD Salinger in ironic fashion used Coming Through the Rye for the title of the novel The Catcher in the Rye (1951), and Bob Dylan acknowledges A Red Red Rose as his greatest inspiration.

Burns was a radical whose poetry strongly appealed to republicanism and Scottish nationalism. His Scots Wha Hae was adopted by Scotland as an unofficial national anthem (Wikipedia) and he was so influential in English literature that he is regarded as having ushered in Romantic poetry before it was ‘officially’ founded in 1798. This is a credit he shares with William Blake. This arises from his radical thought, poetic biases, and from another of his greatest contributions to poetry, that is, his determination to write in Scottish dialect which gave power to his “simple” verses and is among his major achievements. This is linked to his dedication to researching, collecting and recording Scottish folk songs, which helped to preserve them and add to his own poetry and songs in the native language.

Auld Lang Syne is one of the poems that came out of that very old tradition of verses glorifying drink (the tradition is centuries older than Burns) and the valuable corpus of traditional oral verses of Scotland. It has also become Burns’ single most popular contribution to the world. It is itself a tradition linked to Hogmanay (Old Year’s Night) in Scotland and quickly adopted by the whole of the UK along with a ritual of holding hands in a circle which also spread around the world where the English language went. But Wikipedia provides an amazing list of non-English speaking countries and customs where the song features.

Neither is it a mere trivial drinking chorus. It is among the great New Year’s poems that transcend seasonal reference and has depth of meaning as a poem. The lines are often loosely translated from the Scots resulting in inaccurate words and misunderstanding of what it really means. A most common misinterpretation is that it is about forgetting the old and bringing in the new, but that is almost the opposite of Burns’ main statement. Burns took it from one of the several pieces of oral literature that he collected in rural Scotland, and it resembles an earlier ballad by James Watson Old Long Syne printed in 1711. But a comparison of the words show that Burns’ version is more than a transcription and most of it is his own creation. It also shows the greater weight of meaning crafted by the poet.

Firstly, Watson’s 1711 recording is a love song addressed to “my jo” (my love/my dear). Burns makes it not a complaint about a forgotten love, but a message to mankind. He uses the base of the speaker addressing an old acquaintance, who could have been his love, but broadening the sentiments to a more universal reference point. It stresses that times past, old acquaintances and experiences should not be forgotten. The title “auld lang syne” means “old long ago” (literally “old long since”). The opening lines are rhetorical questions and the poem focuses on the value of friendship.

The imagery is consistently tight-fitting. Stanza three refers to time spent by “we twa” (we two) together running about the fields and flowers in the local surroundings, contrasting that with longer distances and weary journeys that have come between them since. Stanza four then refers to them playing about in streams, contrasting that with not expanses of land this time, but “broad seas” that “have roared” between them. While small streams kept them together, the distance separating them is now measured by vast bodies of water.

So why is it a drinking song or verses in praise of drink? And if it is, what makes it superior to the other “simple and wild” ones? It is indeed simple, but deep. Stanza two says “you’ll buy your pint-stowp” and “I’ll buy mine,” while the final stanza mentions taking “a right gud-willy waught” (a good-will draught) which are all references to “a pint” or a drink in the pub. But note that the drink is proposed as a symbol of friendship and good will. It is taken as a ritual or libation to honour the memory of “old long ago” when there was bonding.

What is very important is taking “a cup of kindness” proposed in the chorus. The drink metaphorically becomes kindness of which it is symbolic, and it now takes on the proportion of something which contains the goodness of mankind. In addition, there is Burns’ radical proletarianism. This reunion seems set in a public house, a pub, a tavern or ale house where people will meet for “a pint,” not a castle, a grange, a manor or other upper or middle class dwelling. It is against this kind of setting that they extend a hand to each other of universal friendship.

The New Year then becomes a renewal and a re-establishment of “kindness” and communion values. Mankind is reminded of the importance of remembering old friendships and bonds “for auld lang syne.” That is what Burns has given to the world.