More weight

In reading about small business in Guyana and elsewhere, quite often one encounters the words “entrepreneurship” and “small business” used interchangeably. Those who take the concept of entrepreneurship seriously probably feel offended when the setting up of a stand to sell food or other items is equated with entrepreneurship. The nexus between entrepreneurship and small businesses comes from the fact that entrepreneurs start and operate businesses to exploit some form of change initiated by them or created by others. The European Union (EU), for example, acknowledges that most businesses started in member countries start out as small businesses seeking to “take risks to get the firm off the ground”. But in the minds of those who embrace the concept, entrepreneurship carries far more weight than starting and operating a small business. To qualify as entrepreneurship, the starting of the business must be preceded by a discovery, a change which the new business owner is seeking to introduce to the market. Is the distinction between entrepreneurship and small business that is sought a matter of semantics or substance?

Business revolutionary

In the world of Joseph Schumpeter, one of the earliest economists to recognise entrepreneurship as a different kind of business behaviour, the entrepreneur is identified with more than starting a business. Perhaps, the most significant attribute of the entrepreneur is the ability to innovate or create something that makes a difference in the way we live, the way we interact or in the way we do business. For the likes of Schumpeter, that person was a business revolutionary whose creation led to the destruction of products or processes which were replaced by new and often better ones. Quite often, a new small business is not displacing an existing one. It tends to add to the landscape in the hope that it could share in the market that exists. To be revolutionary, the new small business must displace a large and well-established business and not necessarily another small business. The willingness to take the risk to exploit existing market potential seems to be enough for many to brand the small business owner an entrepreneur.

Destructive force

Our lives are replete with examples of the destructive force of entrepreneurship. One example of a product disrupting the market is the personal computer. The personal computer displaced the typewriter as a means of preparing letters, manuscripts and other written material. Another example of a product disrupting the market is the compact disc or CD which displaced vinyl records as a way of storing and listening to music. The internet has eliminated the telex machine and has drastically reduced our dependence on the fax machine and the postal service. It has brought the world closer together and spawned creations like Facebook which enable social relationships in very large networks to be formed across countries and across cultures without persons having to incur the cost of travel. Among the well-known entrepreneurs who have made these and other changes possible are Bill Gates of Microsoft, Steve Jobs of Apple, Richard Branson of Virgin Atlantic, Mark Zuckerberg of Facebook, and Larry Page and Sergey Brin of Google.

Ties to the innovation

In examining entrepreneurship, one thing that stands out is where the creators of new ideas or products are found. They are found inside and outside businesses. Many new ideas came out of people’s homes, garages, backyards or dormitories and the products or services that the ideas became made it to the market place through the businesses started by their owners. Small firms, in contrast to large ones, are characterised by the involvement of their owners in the management, control and decision-making functions of the business. This closeness between the owner and operation of the business creates risks for the owner, but it also ties him or her to the innovation. The closeness also allows for speed in decision-making, the faster introduction of the product or services to customers and in the way business is conducted. In the context of the development of ideas and their introduction into the marketplace, entrepreneurship and small businesses can be regarded as one and the same.

In large ones too

Entrepreneurs are not only found in small businesses. They are found in large ones too. In large firms, entrepreneurship is seen as action that also has the potential to result in new products, and new ways of doing things that make the firm more competitive. Most large firms are owned by shareholders who are often different from the managers and employees. The creativity of the firm does not necessarily come from the owners or managers, but from employees. The presence of entrepreneurship is reflected in the culture of the organisation where “autonomy allows individuals and groups to be self-directed in the pursuit of entrepreneurial opportunities”. To some advocates of this viewpoint, entrepreneurs come out of work environments where work experience allows employees to differentiate between good and bad ideas. Entrepreneurs therefore are thinking people who constantly evaluate the opportunity cost of working for third parties or for themselves. They come up with ideas and pursue the ideas in the large firm or outside the large firm if they think that it is worth the risk. When entrepreneurship is pursued in the large firm, it behaves like a factor of production contributing to output and profit. When it is pursued outside the large firm, it is a small business.

Young firms

Another viewpoint that impacts the debate about small businesses and entrepreneurship is that of the age of the firm. Gale and Brown in an article released last month favour the argument that it is in young firms and not necessarily small ones where innovation tends to occur. While this viewpoint, on its face, appears neutral on the size of the firm, it exposes a reluctance to conclude that it is smallness that confers a special advantage to businesses in creativity. The argument appears semantic yet failure to acknowledge this distinction could result in unsuitable policy interventions that lead to the inefficient utilisation of public resources. At least one warning that this viewpoint brings out is that the treatment of small business and entrepreneurship as synonyms could result in the misuse of public funds.

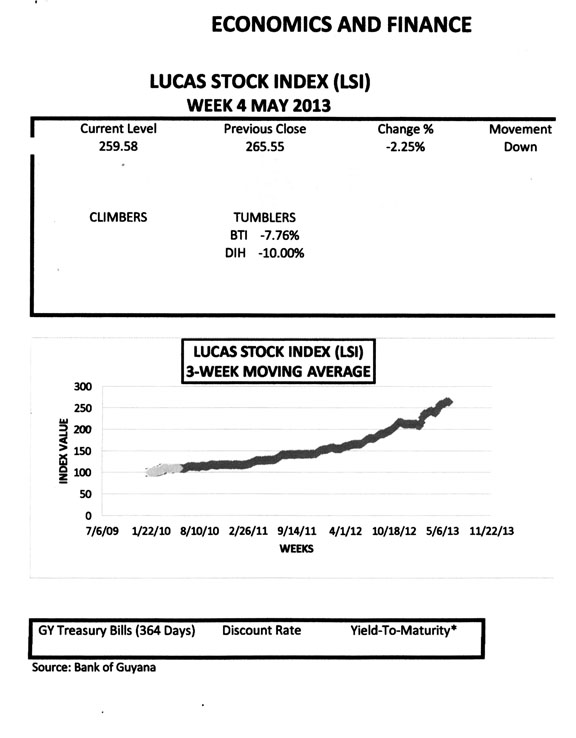

LUCAS STOCK INDEX

The Lucas Stock Index (LSI) declined by 2.25 per cent during the fourth week of trading in May 2013. A total of 160,300 stocks of five companies in the index changed hands. There were no Climbers again this week as the majority of stocks remained unchanged in value. The Tumblers for this week were Guyana Bank for Trade and Industry (BTI) which fell 7.76 per cent on the sale of 25,300 shares and Banks DIH (DIH which fell 10 per cent on the sale of 103,900 shares. In the meanwhile, the price of the stocks of Demerara Distillers Limited (DDL), Demerara Tobacco Company (DTC) and Sterling Products Limited (SPL) remained unchanged after selling 27,800, 500 and 2,800 shares respectively.