The Oxford dictionary gives the definition of apartheid as “a policy or system of segregation or discrimination on grounds of race (and) segregation on grounds other than race.” I believe that this accords well with our everyday understanding of the concept and also indicates why policies of social segregation are normally frowned upon.

Therefore, when the leader of the opposition, Mr David Granger, citing the results of a national examination, is reported as claiming that “education apartheid” is returning to Guyana, the statement is worthy of consideration. This would be so for any country but more so for ours, where the political system does not operate in a manner that would punish those who, consciously or unconsciously, allow the proliferation of such negative policies.

Of course, it is insufficient for Mr David Granger to baldly make the observation, call for an investigation and leave it to others to attempt to decipher what he meant. At the very least, he needed to make a preliminary case by stating more precisely what the segregation is and where and how it is taking place. Since it does not appear that this was done, before attempting his analysis of Mr Granger’s statement, Dr Clarence O Perry, a usually well-informed commentator on education matters, was forced to ask: “What does David Granger really mean by that phrase?”

In passing, the normally objective Dr Perry made some additional claims that deserve our attention if our discourse is not be sidetracked by unproductive controversies. He said that “In 1946 with a Guyanese population of 360,000, there were less than 5,000 students (1.4% of the population) at the secondary level. However, between 1966-1976 (during the PNC’s tenure), there was a significant expansion of educational opportunities, made even more remarkable since this expansion took place within an environment of harsh economic, social, and geopolitical realities. In 1970 there were 21,000 students (2.8%) enrolled at the secondary level.”

We must of necessity ask what happened in the twenty years (seven years of which the PPP was in government) between 1946 and 1966? The following table tells its own story. It shows that all governments sought to improve education access and that the 21,000 secondary students who existed in 1970 had not simply materialised since independence in 1966.

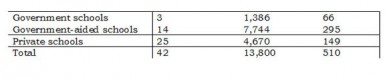

Secondary 1962-63:

# of Schools Pupils Teachers

(UNESCO Educational Survey of Guyana, 1964)

It is also not true to suggest that the economic and geopolitical realities facing Guyana were harsher in the early years of PNC rule: rather the contrary is true. While the PPP regime had to confront persistent attempts at political and economic destabilisation from internal and external forces upon coming to office, in terms of economic aid, the PNC regime was treated as the darling of the West. We may also point to the fact that the education development budget rose from 1.8% in 1957, when the PPP returned to office, to 3.5% in 1963, when it was about to exit (reaching an impressive 8.2% in 1962).

Returning to the main issue, if the problem is one of relative poverty, Mr Granger’s observation raises a host of important questions. Firstly, many poor Indian families (maybe numerically more than Africans given their relative population size) may be suffering similarly from the observed changes in the education system. This would suggest that Mr Granger was making a class analysis: the kind that is prevalent in all societies that allow private education but more so in those where the public education system, though improving, is essentially decrepit.

However, like most APNU supporters, I suspect that Mr Granger was making the claim that Africans are inordinately educationally disadvantaged by the developments in the education sector that penalise those who cannot afford to pay for private education. The implication is that taken proportionately, Africans are poorer than Indians and thus suffer from levels of discrimination that make them unable to pay for education.

If this is so, his focus is too narrow for the social system weaknesses he observed are widespread: affecting health, security, etc. Those who can afford to opt out are doing so with private medical insurance, security guards, etc. Therefore, the apartheid that is observed in the education sector is almost universal and cannot be solved by an inquiry into the education system unless one conceives of the latter as a catalyst for solving the problems of the social system as a whole! Though logically possible, the success of such an approach is highly improbable.

There is a widespread perception among Africans that they are being discriminated against and although in Guyana it appears easier for some ethnic groups to find loans that encourage profligacy than those that support positive enterprise, it is the work of any responsible government to deliberately implement policies that bring ethnic equitability and an end to such perceptions.

Although I believe that those who argue that one cannot prove ethnic discrimination in Guyana are wrong, the necessity to do so is not imperative. In many countries, including the United States of America, the law requires that the way for an organisation to establish that it is not discriminating is for it to show that it has within its membership sufficient members of those who are claiming discrimination.

The situation observed by Mr Granger can only be addressed in an holistic fashion. Thus, the major task for APNU at this stage is to supplement the current sterile parliamentarianism in which it finds itself with an active policy that seeks to transfer to the positive the negative power it now has. This will place it in a position to help to sensibly grow and improve Guyana in an all-rounded fashion and also to prevent the disproportionalities that it perceives are now adversely affecting its constituency.

henryjeffrey@yahoo.com