Today marks the fifth anniversary of the death of the founder and former editor-in-chief of this newspaper, David de Caires. He was born in Georgetown in 1937, and embarked on his working life articled to a solicitor. He was later to open a law practice in King Street with Miles Fitzpatrick, a partnership which was to endure for almost three decades. Law, however, was never what de Caires regarded as his destiny in life, and along with others he made his first excursion into the field of publishing in the 1960s with the magazine New World, which had a political focus and reflected a wide sweep of interests.

New World did not survive, and the “frustrated publisher,” as de Caires liked to call himself, was presented with his real opportunity when Desmond Hoyte acceded to the presidency following the death of Forbes Burnham in 1985. As he often related, at the outset it was not his intention to start a newspaper; rather, he approached Ken Gordon of the Trinidad Express with a view to enquiring whether he had any plan to set one up. Gordon said no, but asked de Caires why he didn’t do so, and offered him all the help he might need. “I left his office in a daze,” de Caires recorded, “vaguely aware that I had embarked on a venture that would radically affect both my career as a lawyer and my life.”

De Caires and Gordon subsequently met Hoyte who indicated that he had no objection to the setting up of a newspaper, although he told them it would not be possible to allocate foreign exchange for the importation of newsprint or other items relating to printing. This was at a period when there was a serious shortage of foreign currency, and the administration exercised stringent statutory controls in relation to it.

Where help was concerned, Gordon was as good as his word, assisting in a variety of ways, including playing a mediating role in the acquisition of a grant from the US National Endowment for Democracy. This grant of US$115,960 covered the printing costs of the newspaper for a year – it was not used for any other expenses – and was paid directly to the Trinidad Express which printed the Stabroek News. The newspaper could not contemplate printing in Guyana at that stage, with all the investment, etc, which this would have entailed, and therefore settled for a weekly publication printed outside the country. The ‘flats’ would be carried on a regular flight to Trinidad and then the print run was flown back in again.

This very onerous task was undertaken by de Caires’ wife, Doreen, who also assumed responsibility for the practical aspects of paper’s operations, including securing their first base in Queenstown. Her husband more than once paid public tribute to her contribution to the development of the newspaper, saying on one occasion, “Without her stamina and courage I would not be here, nor would the newspaper.”

The first edition of Stabroek News rolled off the presses on 21st November, 1986, inaugurating a return to freedom of expression which had been denied during the Burnham years. De Caires has recorded the thrill he experienced when he saw the initial edition after it arrived from Trinidad. Following the acquisition of a press in 1987, making possible the printing of the paper locally, Stabroek News eventually graduated in stages to becoming a daily.

A commitment to the rule of law, an open society and private enterprise undergirded the Stabroek News’s stance from the beginning, in addition to which de Caires intended that the newspaper should be one of record. Where reporting was concerned, he thought it should be balanced and that a comment should be sought from anyone named by a source in an adverse context. While the former editor-in-chief did not consider it was possible to be completely objective, a story, he would say, should not be distorted by bias and there had to be respect for the facts. Editorial sympathies of course would exist, and could legitimately be expressed in an editorial, but under no circumstances, he believed, should they colour an editor’s role as a recorder of fact.

In terms of editorials de Caires did not want the newspaper to be inhibited about expressing its criticisms, although he thought it should be civil, rational and serious, with a view where possible to contributing to the debate. With respect to relations between government and the independent media, he said, “It is not possible to have a cosy or perhaps always a cordial relationship with the government without being in danger of becoming a toothless poodle instead of a watchdog.”

De Caires regarded the heart of the newspaper as the letter columns, more particularly since they were symbolic of the opening up of the society to freedom of expression. This does not mean that the paper would publish factual statements which were known to be inaccurate, or intemperate and provocative language, especially if it was inciteful. The column was intended for serious debate, and such language obscured the issues and detracted from the arguments. However, Stabroek News routinely published letters critical of the newspaper; de Caires believed that people must have a right to criticize the editors and the views they had expressed.

The record on freedom of expression in this country since 1992 has not been without its blemishes, and before de Caires died he experienced a seventeen-month period when state advertisements were withdrawn from the newspaper he had founded in an effort to miniaturise it, if not drive it out of business. This was in defiance of the Declaration of Chapúltepec to which this government is a signatory. The ads were restored before he died, although since his passing we have entered a new phase of a similar problem, this time applied to the independent press as a whole.

Below we present two features in memory of the late David de Caires, one by his son Brendan, and the other by his long-time friend and legal partner Miles Fitzpatrick.

Remembering David de Caires

By Brendan de Caires

“My father always said one wasn’t a man and knew nothing of life until one could read the local newspaper from cover to cover and find every item interesting.” So says the all-too-human priest who narrates Andrew O’Hagan’s novel Be Near Me. David de Caires, my own father, phrased most of his opinions with a solicitor’s circumspection, but he felt much the same way about local newspapers. After 30 years of toil in the vineyards of the law, he came to journalism with a convert’s zeal, determined to restore a modicum of pride to a society that had almost lost interest in itself. In the wake of the Burnham years the quixotic idea of opening an independent newspaper appealed to two of his great passions: educated wagers on apparent underdogs, and politics. He pursued both with an idiosyncratic and, with retrospect, rather Catholic blend of immersive curiosity in the things of this world, and quasi-monastic detachment from them.

To understand him, one must embrace his contradictions. He covered the minutiae of local politics in the hope that we would learn the need for a less politicized, or at least a less partisan, society. He spent a large fraction of his leisure engrossed in the arcana of horse-racing — at one point we even owned a telex, which roused itself for half an hour after lunch to print race forms for the next day’s outings — yet he disapproved of impulsive gambling and would never, for any reason, have been foolish enough to buy a lottery ticket. He lapsed from conventional Catholicism into secular humanism but never held dogmatic opinions about anything. “Thou shalt not follow a multitude to do evil,” says the book of Exodus. Though I never heard him cite the verse, it was an admonition he took to heart.

Like me, he admired freethinkers and espoused a broad tolerance of dissenting opinions. He was an unapologetic capitalist and held socially conservative opinions but none of his views ever hardened into doctrinaire certainty. He thought that every society had to learn how to make its way in the world, even if this meant stumbling for a while through avoidable political errors. He had little patience for the undigested, pamphleteering Marxism of the PPP, but none whatsoever for the dictatorial instincts of the PNC. A miserable adolescence in Jesuit boarding school had given him a lasting grasp of what powerlessness felt like, and he never overcame an inherent scepticism towards groups —political, religious or racial — who claimed to understand our interests better than the rest of us.

His political opinions seem less than coherent if viewed superficially — which, I hardly need say, was how most party leaders insisted on viewing them. Perhaps this is understandable, because although he lived in a culture that took everything too personally, I have no recollection of a political abstraction ever interfering with his private friendships, or tempting him into facile judgments. Although he was a lifelong anti-Communist, several of his closest friends were Communists, or former Communists. Walter Rodney and Maurice Bishop, two of the few political figures he really admired, were hardly exponents of his more measured political views. I think of him as conservative with a small “c” and, at the same time, somewhat paradoxically, as fond of several figures on the left. He told me more than once that he felt the Fabian Socialists seemed to have the most mature and practical ideas of how lasting political change came into a society. In other spheres he always preferred tolerance to certainty. Despite his private reservations about the erosion of faith and traditional marriage, for example, I am certain he would have been delighted to learn, posthumously, that the trust set up at our family home has hosted meetings for the Society Against Sexual Orientation Discrimination, and given voice to people who might otherwise have felt excluded from a certain kind of Georgetown gathering.

His tastes in the arts were varied and largely mid-brow. He loved jazz — Charlie Parker, Miles Davis and Sarah Vaughan were in the pantheon — and more predictable fare like Sinatra and Sammy Davis Jr. He was suspicious of the aims of high modernism, but loved “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock” as much as the next man. He was even willing, after some persuasion, to concede the genius of James Joyce and Ezra Pound despite their obscurities.

Stabroek News mattered more to him than anything outside his family. It drained his energy and shortened his life, but it also gave that life meaning. Years of vetting the Catholic Standard for libel had given him a strong sense of how a newspaper of record might refocus a culture. At its best, he thought it could reshape the political landscape, reintroduce some lost civility and indicate where compromises might be found. If it remained aloof from party affiliations and actively sceptical on the public’s behalf, it might even make a modest contribution to the society. His Stakhanovite labour over the editorials and letter pages were attempts to give voice to ordinary Guyanese who had been marginalized by the political squabbles which had ruined the country. Somehow, despite much evidence to the contrary, he never lost hope that we could climb out of the rabbit holes of the Sixties if we could only transcend the racial and ideological fixations that had overwhelmed us in the first flush of independence.

Sifting through decades of memory, I find an almost filial dedication to Martin Carter to be a recurrent theme. Dad spoke of Martin with reverence, and he treated the great man’s occasional descent into drunken rants, as mere distractions from his mercurial brilliance. Martin was a Guyanese Trotsky, a man who had seen deeper into the national soul than his contemporaries, and had paid a terrible price for the knowledge. My father was devoted to Martin for having the courage, and the intellect, to have done so. One of Nietzsche’s best aphorisms ends with a phrase that always brings this aspect of Martin to my mind: “when you stare too long into the abyss, the abyss also stares back into you.”

It is worth dwelling on the many meanings of Martin a little longer — he was, after all, asked to turn the sod for the construction of the building that houses this newspaper’s press. Recalling his first encounters with the Carter Brothers, drunk with literature (Easter 1916 and Pericles’ funeral oration were often declaimed at great volume) and a great deal of rum, my father always said that beneath their incandescent anger there was a palpable love for this country. The vituperation that flowed so easily when the liquor was upon them was provoked by the pangs of disprized love rather than the vitriol of genuine contempt.

Dad often told me that he felt Martin had a much higher opinion of his friends than they did of themselves. Part of what made him such a powerful moral force was that his intense confidence made you want to live up to the accompanying expectations. Martin’s attitude was profoundly patriotic, in the best sense, for it assumed that we could discharge the responsibilities that came with political independence, providing we took ourselves seriously. That assumption was central to my father’s view of the role Stabroek News should play in this society, and it remained an enduring motivation during the last 20 years of his life.

Five years after his death my father remains a living presence for my family. His countless acts of kindness unforgotten, his wonderful open laugh sorely missed. In my better moments, I like to think that the continuity of staff at this newspaper, and its carefully guarded editorial independence, have also kept his legacy alive for other Guyanese.

Memories

By Miles Fitzpatrick

Stabroek News began as a weekly paper printed by the Express Printery in Trinidad and flown to Guyana. The first issue carried a description of the parlous state of electricity generation in Guyana based on a report which we were not supposed to see.

The next issue had an account of the hanging of a young man who had probably not committed the offence he was executed for, whose “accomplice” shouted on the scaffold “hang me. Not him; he wasn’t there”.

Its next task was the most difficult for a new newspaper in Guyana. It relentlessly, day in day out, exposed the corruption of the electoral system in Guyana. Its exposure of the working of the Bollers Commission depended heavily on the reports of Clement Rohee, one of the PPP nominated Commissioners, who refused to keep silent in the face of a Commission that in practice amounted to the protector of a rigging mechanism.

To some this seemed like an unusual “alliance”. A marxist spokesman and a pro capitalist editor. But David de Caires was not an ordinary person. He had a rendezvous with the truth as he saw it, which usually was what it was in fact.

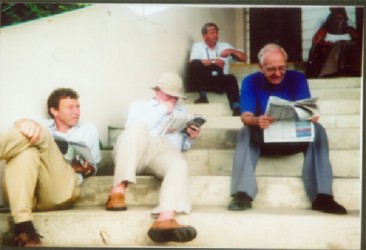

After his first heart attack he knew that if he continued his work the strain could endanger him. But one dies anyway, and Dex was happiest when bringing out the paper as part of a team – except possible when picking a winner. There is a photograph taken by my wife of David, his son-in-law Mike and myself at Plumpton race course – a small National Hunt course in England with stands unencumbered by seats. A “jumps” meeting with no great horses in attendance. Just the basic fare of horse racing.

De Caires sits comfortably on the concrete, engrossed in his racing paper looking for a winner – and at peace with the world.

That is how I remember him.

The seeds of his lifelong love of watching and betting on horses were sown at Stonyhurst, an ancient and forbidding Jesuit public school in middle England. In the 1950’s he was one of the children of Guyanese catholic businessmen who were sent to Stonyhurst and like many of them, did not have available the modern return to Guyana on holiday. At least one of his summer holidays was spent on a farm. I remember a distinguished West Indian economist telling me that when he first met his son after sending him to a similar institution he asked him: “how was school?” His son replied “Alcatraz!”

The loneliness particularly at holidays begged for diversion and he found it in racing – the little tracks near enough to make the occasional train trip to, and bets with the bookie around the corner from the school.

He quickly became an expert on form – horse racing and breeding is the most highly documented sport in the world. And when we set up practice in King Street two hours of his morning were devoted to listening as he worked at his desk to the English races on which he had bet. Clients with an emergency saw me if I wasn’t in court during these hours, and must have wondered at the excited voice of the race announcer coming from Dex’s room next door.

Then we started “Turf Accountants” in the bottom flat. As with the bookshop in Camp Street, Doreen was soon called in to create order out of chaos. Inevitably, the Chief Justice called us into his Chambers.

It had been reported to him that the legal office of De Caires and Fitzpatrick (Bayney Karran’s name had not yet joined our letter head) was running a betting parlor – a “bookie shop”! He reminded us that we were “Gentlemen of the Bar” and this endangered our status – He spoke of our parents and our responsibility to our families.

David rose to the occasion. He explained to a bemused Chief Justice the intricacies and elevation of the “Sport of Kings”. He said that in the mother country of our Common Law there were firms of professional “Turf Accountants” that were not mere bookies. We left with, if not judicial approval, at least with bemused acceptance.

I don’t think Dex had a full understanding of what starting Stabroek News would entail. The leap from New World Magazine and Fortnightly was immense.

But he was a bull dog in that respect. He put his head down and ploughed on, learning as he went. He had institutional support. The leading West Indian papers took symbolic shares in Guyana Publications, sending a signal that said “if you touch Stabroek, you touch us.” The Express printed the weekly paper in Trinidad initially.

But he had to do two things. He had to give up his legal practice, which he didn’t mind apart from initial financial considerations and he had to persuade Doreen to manage the enterprise. The irony there was that Dex, the son of a successful businessman, was not comfortable in that role. But he learnt the newspaper business from the bottom up.

In my humble opinion Stabroek News came of age in the 1992 election. It had a clear mandate to oppose another “fix” and to support the Carter initiative, particularly on counting at the place of poll. And its reporting of the election campaign and especially the day and night of the vote reached the highest levels of professional journalism.

At the Commission during the day (I was the member nominated by the ‘small parties’ basically the WPA at the invitation of the PPP) I became increasingly concerned at the hostile crowds which eventually caused the Election Commission staff to evacuate the building (except Rudy Collins who, in a historic moment, refused to leave) and broke every window of it.

I tried to get David to close the Stabroek News office, as the attention of some of the mob was increasingly drawn to the Stabroek building in Robb Street. Groups of men were passing the building coming from outside the Commission office and shouting threats. “You going bun tonight.”

David’s response was to tell the staff that anyone who chose to go to his or her family would be respected. Few left, and the paper the next day was a historic document of a vital moment in Guyana’s history. Han Granger’s article from the middle of the street protesters was I believe one of the best accounts of a public crisis in a Guyanese newspaper, that alone justified the risk of working through the night.

There are so many memories.