(The following article is an edited version of a ‘History this week‘ column which was first published in Stabroek News on February 17, 2000 under the caption ‘The 1763 Uprising’.)

The 1763 Uprising is one of the great risings of the Caribbean. Never mind that even at its height it involved less than 4,000 people; never mind that it occurred in one of the region’s least-known and economically backward plantocracies; never mind that it failed – with the exception of Haiti, so did they all. No, the events of 1763 are unique in terms of slave revolts in the Caribbean in several respects, and eerily prefigure the revolt in St Domingue nearly thirty years later, which was to produce the independent state of Haiti.

The first independent Caribbean state?

The first thing which is remarkable about the early leaders of 1763, is that initially, at least, their intention seems to have been to set up what we would now consider an independent state, as opposed to a maroon community.

Exactly how many of the revolutionaries subscribed to this idea, we shall never know, but that this was Coffy’s plan we have not just from hearsay, but also in writing. In a letter to Van Hoogenheim, the Dutch governor of Berbice, Coffy proposed the partitioning of the colony into upper and lower Berbice, the revolutionaries keeping the upper half, and Van Hoogenheim, the lower.

It is to Ineke Velzing, a Dutch historian who has researched the Interrogatories – the inquiry-trials that were held in 1764 – that we owe some of our information concerning what Coffy did shortly after assuming control of most of Berbice. Contrary to what generally happened in Caribbean revolts, Coffy in the early days maintained the plantation system in operation. He placed ‘masters’ on the few sugar estates in the territory, apparently with the intention in the long run of producing sugar and kilthum (a rudimentary form of rum) which could be traded with the Dutch for the things which the revolutionaries wanted. Masters who performed well on their estates, such as Fortuijn and Accara of the Brandwagt (not to be confused with Accara of Lelienburg), were sometimes rewarded with high office. Fortuijn was eventually to go on to become Governor of Canje, and Accara of the Brandwagt, who turned traitor in 1764, was made his military commander.

Accara of the Brandwagt had been put in charge of Plantation Dageraad during the period when the Dutch had abandoned it in early March, 1763. Subsequently, while stranded in the company of disaffected planters and a small military force near the mouth of the river. Van Hoogenheim received reinforcements from Suriname. This emboldened him to sail upriver again to Dageraad and set up a fortified position there. When the Dutch reoccupied the plantation, they found everything in working order.

In the initial stages of the rising too, a money-based economy was retained. We do not know exactly how the money was earned or acquired, but according to Velzing, one source says that beef was sold at various points along the river at a fixed rate per pound.

Coffy does seem to have had some administrative skills; Velzing says he sent Atta upriver, for example, to do an inventory of the people and the cattle in that area, and he identified people on various plantations to grow provisions. The revolutionaries were not allowed to converge on his headquarters unless they were being trained to serve in the army, nor do they seem to have been permitted to roam around as they pleased. In general, one gets the impression of attempts being made to introduce a measure of orderliness into what was, after all, a rather novel situation.

The one sour note in all of this which deserves mention, is that slavery was not completely abolished either under Coffy’s administration, or that of Atta, who eventually succeeded him.

Coffy decided that the slaves attached to the plantations of the Dutch company which owned the Colony of Berbice, were not to be trusted. Unless they had committed some overt act of hostility against the planters, therefore, their loyalty to the cause was deemed to be suspect and they retained their slave status. It was they who provided the labour on the former Company-owned estates for the production of sugar.

Coffy instituted a form of government which paralleled the Dutch one very closely. There was a Court of Policy chaired by Coffy as Governor, with Councillors and a Secretary. There was also an executioner. The Secretary was Prins from the plantation of Helvetia who was literate, and is thought to have written at least one of Coffy’s letters to Van Hoogenheim at his dictation.

Military approach

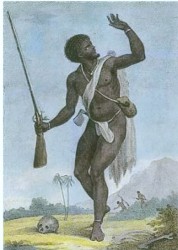

In addition to the initial concept of some kind of state, with a formal government structure in the colonial mould and what may have been the intention of having a money-based economy, the leaders of the rising distinguish themselves from their contemporaries elsewhere in the Caribbean in another way. From the very outset they committed themselves to the use of European weapons, and the battle tactics which were necessary for the successful employment of these.

Neither Coffy nor Atta who came later, believed that the Dutch could be defeated by throwing ill-armed men into the field to charge in disorganized fashion at soldiers in formation carrying firearms. Troops were drilled in the European mode; soldiers had to learn to handle flintlocks and matchlocks, and, as stated above, the battle tactics which went with them; plantations were scoured for gunpowder and saltpetre with which to make ammunition; and weapons were repaired by a blacksmith called Prins who had been attached to the Fort.

While the revolutionaries did, in the end, lose, theirs was no ignominious defeat. The insistence of Coffy, Accara and Atta that their army be well trained paid off on the battlefield, and was one of the reasons why the revolt lasted for so long – about a year altogether. Even the two major revolutionary losses of the war – the two Battles of Dageraad – were a long way from being total routs. What did defeat the leaders was quite simply their inability to replenish their stocks of ammunition, and to a lesser degree their firearms.

The highest rank in the army, held by Coffy himself and his military commander, Accara of Lelienburg, was that of captain. It was the highest rank on the Dutch side, and was held by Van Hoogenheim and the most senior Dutch military officer in Berbice, Captain-Engineer Hattinga. The other ranks paralleled the Dutch ones too; Cossael, the Congo-born officer who led the attack on Peereboom as well as Atta, for example, were lieutenants.

It must also be said that there is some evidence that Coffy did think strategically in so far as he attempted to spread the revolt to Demerara. Part of his reasoning, we are told, was to tap new sources of ammunition and weapons, but it is possible that he may have understood the importance of instigating rebellion in neighbouring colonies to ensure the long term survival of the new state.

In the second Battle of Dageraad on May 13, 1763, which Coffy planned very carefully, Velzing says Coffy’s aim was to capture a ship’s cannon. This, he thought, quite rightly, would give him some control of the river and would make it difficult for the Dutch who would have to drive up the river if they wanted to repossess the territory. If his strategic thinking was correct, his tactics were certainly off centre, and the cannon he wanted to seize did serious damage to his forces.

The Coffy-Van Hoogenheim correspondence

The case of Haiti excepted, Coffy’s correspondence with Van Hoogenheim is almost unique in the annals of regional revolt. The two remained in contact either by letter or via verbal messages almost up to the time of Coffy’s death. At least in the beginning, Coffy wrote and sometimes negotiated in good faith, although later on he challenges the Dutch governor in relation to his motives. At all stages in the correspondence, Van Hoogenheim answered in order to buy time.

In these letters written at dictation either by some of his captives, Secretary Prins of Helvetia or a German soldier belonging to a group which had defected from the Suriname forces, Coffy set out the causes of the rising. He indicted a group of planters from his own area, including Anthonij Barkeij who owned Lelienburg from which Coffy himself came. On the list too were some officials from the company which owned the colony of Berbice and who were related to Barkeij through marriage, as well as Captain-Engineer Hattinga from the military. These men (and one woman), said Coffy, were guilty of great cruelty, and had not been giving “the slaves their due” ’ – i.e. had been withholding rations.

He confirms in one letter the view held by historians on the basis of other sources, that the uprising had begun prematurely, and indicates that he had not approved of this. More problematically, he apologizes for the first Battle of Dageraad on April 2, which was undertaken by Accara, his field commander, without his authority.

Coffy also tried to persuade Van Hoogenheim in the letters to come and negotiate face to face with him, with no success: “Your Honour need have no fear,” he writes. On the subject of slavery he tells his Dutch counterpart: “But your Honour should not think that the Negroes want to be slaves again. The Negroes that your Honour has on the ships can be your Honour’s slaves.” In a later piece of correspondence he tells Van Hoogenheim: “…you should also see to it that you get new slaves, for we are free.”

As stated earlier, the matter of partitioning Berbice is raised in the letters, but not surprisingly, Van Hoogenheim prevaricates in his replies: “The Lord Governor [i.e. Van Hoogenheim] cannot understand what you really want to say by asking him if he has changed his mind about arriving at an agreement with you concerning the Land of Berbice…” he writes. (The Dutch Governor’s letters are written in the third person.)

At one point Coffy tries to strike a deal over the return of two Dutch sisters whom he held, the elder of whom he had made his wife. That too fell on deaf ears, although Van Hoogenheim indicated in principle his willingness to do a deal in relation to them.

In his second to last letter Coffy returned to the matter of the planters of Berbice: “…Messrs planters and directors are the cause of this war as they have severely mistreated the people and have treated them to floggings and whippings beyond tolerable limits. We could not bear that any longer as we do know that God is God who rewards virtue and punishes evil.”

The letter was dated August 2, 1763, and it was followed by another five days later. Thereafter, Coffy fell silent.