(An edited version of a ‘History this week’ column which was published in Stabroek News on February 24, 2000)

The story of the internecine strife which occurred among the revolutionaries in 1763 has passed into popular folk-lore. But was that really the reason why the rising failed, or were there some other contributory factors to its collapse? Furthermore, did it have any hope of success?

Geography

signature with the flourishes characteristic of the period leads the signatories on the right-hand page.

One factor militating against successful revolt was simply that Berbice was a relatively small colony, which could be sealed off from neighbouring territories. That was something which would not have been possible in the case of Essequibo, for example.

The Berbice plantations were strung out singly along both banks of the river, perhaps as far as nearly one hundred miles upstream, and while there was bush in some parts, vast expanses of forest such as were a feature of Essequibo, did not exist. The landscape of Berbice gave the Dutch, not the revolutionaries, the advantage, and it is simply not known whether the latter formally addressed the possibility of being hemmed in by their enemies.

As will be discussed below, they did attempt to spread the rising to Demerara, but the full thinking behind this move is not altogether certain.

In general, other than their familiarity with the plantations on the river, the revolutionaries and their leaders displayed a woeful lack of knowledge of the larger geography of the territory in the first few months of the rising.

The Caribs of Essequibo

The second factor – a most important one – militating against successful revolt was the Amerindians. Strangely enough, it was not the Berbice Amerindians who presented the problem, it was the Essequibo Caribs.

Under normal circumstances, there was a population of Arawaks and Warraus living behind the Berbice plantations, who hunted and fished for the planters, and sometimes even acted as go-betweens when the slaves had complaints they wanted to relay.

Behind the plantation Amerindians were the bush nations – in this case mostly Arawaks, with Akawaios higher upriver. Most of the time they acted as a screen against the establishment of maroon encampments (there were exceptions), and any Berbician would-be maroon knew that his best chance of survival if he ran away was to make straight for Essequibo. The Great Uprising of 1763 became possible because of an epidemic in the colony – it may have been yellow fever, but no one really knows – which caused the bush nations and many of the plantation Amerindians to move out to neighbouring territories for the duration. Conspirators, therefore, could plot a takeover of the colony secure in the knowledge that the screen was down for the very first time since 1687, when the Arawaks joined the Africans in a revolt against the Dutch.

Whether Coffy and the other leaders understood the extraordinary danger that the Caribs of Essequibo presented to the long-term success of the rising is not known, but it is very unlikely that they did. Technically speaking, there were no Caribs living in Berbice, and not surprisingly, information on Essequibo available to the revolutionaries seems to have been sketchy.

The Caribs had evolved a fiercely anti-Spanish stance since they had first encountered the conquistador Herrera in the Orinoco River in 1534, and the Spaniards regarded the reduction of that nation as the key to their successful occupation of the Orinoco and its environs. They first reduced large numbers of Caribs living in the Guarapiche River to the north of the Orinoco, and by the time of the 1763 rising, had been turning their attention to the huge swathe of Caribs south of that river, and in the Imataca.

The Caribs understood very well that their survival as a people depended on them being able to eliminate the militarized Jesuit and Capuchin missions which were the instrument of Spanish penetration in the region. This necessitated them having a safe haven from which to operate, a plentiful supply of European firearms and a good grounding in European battle tactics.

The safe haven and the base from which to operate were provided by the Dutch colony of Essequibo, and the Carib-Dutch alliance remained solid for the entire duration of Dutch occupation in our Guyana.

The firearms came on occasion from the Dutch authorities, but usually from private Dutch sources, paid for by Carib slave-trading activities outside the boundaries of the Dutch sphere. Their Amerindian slaves were sold partly in Essequibo, but mostly in Suriname, where there was a much bigger market for them. Their interest in the preservation of the Dutch colonies in the Guianas, therefore, also had an economic dimension, since as the late anthropologist Neil Whitehead pointed out, through their slave-trading activities they became the main distribution agents for European goods among the Amerindian nations in this part of the continent.

Needless to say, the Caribs were also very familiar with European battle tactics, as the Spanish missionaries learnt to their cost. Furthermore, unlike the revolutionaries, the Caribs had a thorough grasp of the geography of the region, roaming as they did between French Guiana, the Rio Branco and the Orinoco River, and they were in touch with all branches of their nation. When assessing their strategic options, therefore, they took the large view.

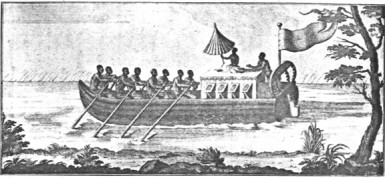

When called out first by the Governor of Essequibo, who asked them to go to the assistance of the Governor of Berbice in early 1763, they did not respond immediately, because they were engaged in one of their many wars with the Akawaios of the Mazaruni. When they had settled that matter, however, they came out in the largest numbers ever seen for any military enterprise up until that date. According to the accounts, they did it with enthusiasm; their political and economic future was bound up with the survival of the Dutch plantation system in the Guianas, and they were not slow to grasp that fact.

This, then, was the nation which the Dutch put into the field against the Berbicians. Experienced in the handling of firearms, battle hardened in innumerable encounters with the Spaniards, possessed of an unsurpassed knowledge of the terrain, and harbouring their own private motives for wanting to put down the revolt, the Caribs were no easy foe. It was they, together with a few Demerara Akawaios and Arawaks, who formed the net thrown by Van Hoogenheim around Berbice, and the revolutionaries under the command of Accara of Lelienburg, failed to defeat them in battle.

Foreign troops

By 1764. the small colony of Berbice had become host to large numbers of troops from outside, particularly from the Netherlands itself. Their role was vital in suppressing the revolt, but as Van Hoogenheim realized, the likelihood of them succeeding so easily had the Caribs not been in place was probably not as great as might at first glance be supposed. Once the net was there, however, there was simply no possibility that Atta and his forces could resist the overwhelming firepower (and manpower) which the troops sent by the States General and the Society of Berbice represented, no matter how unified or otherwise they were.

Arms and ammuntion

Whatever grandiose plans Coffy may have had in mind in 1763, his capacity for action was limited by a severe shortage of arms and ammunition, particularly the latter. His anger with Accara of Lelienburg for engaging the Dutch in the first Battle of Dageraad on April 2, 1763, may well have been related to the need to conserve gunpowder stocks. When he did eventually commit himself to battle on May 13, he planned it carefully, with a view to delivering the Dutch a monumental blow, and capturing a boat mounted with ship’s cannon.

The second Battle of Dageraad, while not an ignominious defeat, was a defeat, nonetheless, and thereafter Coffy seems to have only committed his army to action when he had no alternative, such as at Savonette when the Caribs began to make their appearance.

Some ammunition came his way in June, when deserters from the Suriname forces who had mutinied against their commander joined up, but that was not sufficient. A plan to spread the revolt to Demerara in order to tap new sources of powder failed because the leader of the commandos, Prins of Helvetia, could not find his way along the bush paths.

Coffy also tried to negotiate with Van Hoogenheim for a barrel of gunpowder in return for two Dutch sisters he was holding, but the Dutch Governor would have none of it.

According to Hartsinck, before he committed suicide, Coffy buried some of the gunpowder he had under his control, and more was wasted when the revolutionaries fought among themselves. While small maroon encampments deep in the bush somewhere might have survived on more limited stocks of ammunition, the full-fledged state which Coffy had in mind definitely could not. At no time, however, does he appear to have considered adjusting his modus operandi, or his vision of the future.

Strategy and tactics

The evidence on matters of revolutionary strategy, etc, is patchy, and some conclusions have to be inferred. But first a word about Dutch strategy.

Van Hoogenheim devised his strategy for dealing with the rising right at the beginning, and he never wavered from it. He decided on it after consultations with Captain-Engineer Hattinga, who was a qualified surveyor, and knew the topography of Berbice better than anyone on the Dutch or the revolutionary side.

Hattinga was an alcoholic, but he was not drunk every day; he was a binge drinker, and fortunately for Van Hoogenheim, one of his lengthier periods of sobriety coincided with the beginning of the revolt. However, he did eventually get himself dishonourably discharged after a drunken spree in the Canje River.

As explained above, Van Hoogenheim resolved to throw an Amerindian net around the colony, and then sail with Dutch troops upriver and drive any who did not surrender into the net. After securing the Canje flank first, following which the revolutionaries there fled to the main river, this was the strategy which was followed at the end of 1763. Despite all the reinforcements which came into Berbice from March 28 onwards, the Dutch Governor resisted the temptation of using them to attack the revolutionaries before the Caribs were in place; he was afraid that they would set up small encampments far from the river, and that they might never be rounded up again. He was also fearful of the establishment of a trans-border maroon community, with the Berbice revolutionaries linking up with the Saramakka of Suriname – something which was certainly discussed in the revolutionary camp.

Where Coffy was concerned, the first thing that has to be noted is that there was probably no agreement among the leadership about the final aims of the Uprising, and therefore there could be no agreement about strategy and tactics. While Coffy’s vision predominated at the very outset of the rising because the Creoles prevailed, it soon became clear that there was a split between the Creoles and the Africans. Eventually, the Africans took over the revolt, and the evidence strongly suggests that an independent state was not what they had in mind; exactly how they saw the future has never been determined, but judging from the sequence of events, they may have been looking to establish maroon-style encampments, each of the four African nations represented in Berbice having its own.

Coffy’s military strategy and tactics to achieve his end, however, are something of a puzzle. He was presented with a golden opportunity in March, 1763, when the Dutch were hanging on precariously in Fort St Andries at the very perimeter of their former colony. For reasons which are hard to explain, he elected not to fight them there when they were exposed militarily speaking, and at their weakest. Instead, Accara of Lelienburg led an attack on them when they had already received reinforcements from Suriname, and had sailed back upriver fortifying themselves on the more easily defended plantation of Dageraad.

There are several instances throughout the course of the revolt when the Dutch were laid low by the epidemic, and their morale was poor, yet the revolutionaries still did not launch an attack. The least that can be said about it is that their intelligence was inadequate; Van Hoogenheim had a rather better picture of what was going on in their camp than they had in his. Intelligence as to what was happening on the Dutch side was critical to the revolutionaries’ long-term future.

Limited stocks of ammunition, among other things, seem to have persuaded Coffy to try and deal a crushing blow to the Dutch on May 13, at the same time capturing a boat armed with cannon which would have allowed him to dominate the river. He was mistaken in thinking that he could capture a boat in a pitched battle situation, however, and once he lost that battle he seems to have run out of ideas as to how to proceed.

The two main battles of the war, therefore, were wasted; the first, on April 2, should never have been fought at all, and the second on May 13, while it had good strategic aims, these could not have been achieved by the methods used.

While he negotiated a truce in the lower river with Van Hoogenheim, the Caribs were beginning to appear in the upper river. Coffy appears to have understood the immediate threat that they represented since he sent Accara of Lelienburg upriver to deal with them, but whether he appreciated that these were just the vanguard for large numbers of

Caribs who would seal off their escape, is difficult to say. Either way, he does not seem to have had a strategy to deal with the problem.

The most successful war theatre for the revolutionaries turned out to be Canje, where Fortuijn was in charge with Accara of the Brandwagt (not Lelienburg) as his army commander. They won their battles against the Dutch until Captain Haringman’s flotilla appeared in November 1763 and they fled to Atta in Berbice.

On the main river, ironically, the most successful period militarily for the revolutionaries was when all appeared to be lost, and Atta conducted a brief guerrilla campaign in the region of the Wikki creek. Some of the Africans who dominated the army would have had experience of guerrilla warfare in terrain not dissimilar to that of Berbice, but Coffy never seems to have entertained it as a means for achieving his ends. By that time, however, the African leaders had set up camps in the bush from which they made guerrilla sorties, and Coffy’s state had long since been forgotten.

Strategically speaking, Coffy may have failed to recognize that if he could not spread the revolt beyond the boundaries of Berbice, its chances of success were automatically jeopardized. There was the failed Demerara expedition, but as mentioned above, the full thinking behind that, aside from the need to get more arms, etc, has never gone on record. In any case, planter Gedney Clark who had Barbadian connections, moved to protect Demerara, and a rising there might simply not have been viable.

As mentioned earlier, there was some talk at a later stage of linking up with the Saramakka of Suriname, but nothing concrete seems to have been done about that either.

In the end, all Coffy had to fall back on was negotiating with Van Hoogenheim, but unfortunately for him the latter was not negotiating in good faith. Eventually too, it was the letter-writing which led to the challenge from Atta, who did not approve of it, and Coffy’s eventual suicide.

Internecine strife

The extent of the internecine strife on the revolutionary side cannot be underestimated. Somewhere towards the end of 1763, two African nations – the Delminas and the Congos –actually fought a battle on the plantation of Essendam. It was in this battle that Accara of Lelienburg was killed.

The problem revealed itself under Coffy’s administration as a struggle between the Africans and the Creoles; however, after the Africans took over total fragmentation occurred with each section of the army following its own nation chief. For all of that, it has to be recognized that even without the internal quarrels and fighting, given the other factors involved the rising most likely would still have failed.

Conversely, had Coffy been more successful than he was in the first three months of the revolt, he might have been able to hold the disparate elements in his army and political structure together for much longer.

Could Coffy have won?

This is not a simple question, but the quick answer to that is that on the face of it, probably not. Had he succeeded very quickly in spreading the revolt to neighbouring colonies, his chances of success would have increased immeasurably. In that eventuality (although he could not possibly have been able to factor it into his calculations at the time), he might have secured some outside assistance in the form of the Spaniards, who were committed in a secret pact to dislodging the Dutch from the Guianas.

If he could not spread the rising, then his best hope in a small territory like Berbice, would have been to give up his dreams of a state, and go for maroon encampments in the bush, well away from the river.

Whether the Caribs could have dealt with all of those, is perhaps a moot point, but at least there would have been a chance of some of them surviving.

It is also moot as to whether the Saramakka of Suriname would have given the revolutionaries any assistance if asked, let alone form an alliance with them or allow them to join their group. In general they adhered to the terms of their treaty with the Dutch of Suriname and they might not have been of a mind to jeopardize their status.

Finally, of course, if the revolutionaries did not manage to link up with the Saramakkas or spread the revolt to neighbouring territories, it is likely that enough forces would have been sent against them from Europe in the end to put down their ‘state,’ even if they had been more successful in the beginning than they actually were. Geographically, Berbice was not St Domingue, and from a demographic point of view, numbers were tiny. The Dutch would not have allowed less than 4,000 people to undermine their grip on the Guianas, more especially if the Spaniards were giving the revolutionaries any help. In addition, of course, the Dutch could depend on the assistance of the Essequibo Caribs at any time.

The revolutionaries of 1763 had most of the odds stacked against them; that they got as far as they did does them enormous credit.