By Ineke Velzing

An edited extract from Velzing’s unpublished MA thesis, University of Amsterdam

Revolutionary plans

The uprising was a premeditated plan in which slaves from various plantations were involved right at the outset. It was begun and initially directed by the Berbice slaves.

During his hearing in 1764, Bomba Cupido of Hollandia said the following: “Says that he heard that the people of his plantation, of Juliana, of Lelienburg, those of Van Staaden and those of Altenklingen were to begin, and that thereupon he went straight away to Michel Schneijders, returned with him to his plantation and recommended that he keep an eye open and then returned back; subsequently, Alexander of this plantation went to Lelienburg and said that the bomba had given them away to Michel Snijders and that it was now high time, because otherwise the Christians would come.”

Subsequently he told the inquiry: “When he came back again with Michel Snijders, Coffy was there and he then went home again and started on his plantation, Lelienburg, made himself master of all the guns, powder, shot and everything, and then returned with all those goods and drums.”

To the question of who first started talking about the Uprising, Damon of Lelien-burg replied: “The word first came from Hollandia and Zeelandia, from the Negroes called Attaba and Atta of Altenklingen, Nouakoe of Hollandia and Amina Quakoe of Nieuw Caraques.”

When asked to whom did Adam of Hollandia and Zeelandia speak about starting the war and killing the Christians, Damon’s response was, “…Jan Bart, Jan, Sangoe Coffy, Quakoe of de Prosperiteit and Quassie of Schirmeister spoke together about it, but when the war started, he [Damon] was in the bush and did not have enough time.” Furthermore he stated: “The agreement was that Coffy would be the boss,” because he “was such a wise and intelligent man.”

From all of this it can be concluded that right from the outset the various plantations were in contact with each other, such as Lelienburg, Hollandia and Zeelandia, Juliana, Elisabeth and Alexandria (Van Staaden was manager there), Altenklingen, Nieuw Caraques, Prosperiteit and probably others as well. It can be taken as established that Coffy was singled out as leader, especially as right at the beginning Coffy appears in the forefront as director and organizer.

Supposing that Cupido‘s statement is true, then the Uprising would have started earlier than had been planned. However, this could not be verified. In any event, the Uprising began on the 27th February on the above-mentioned plantations. This was a very propitious moment, as it was a Sunday and a free day for the enslaved. As they were together, communication with the adjacent plantations was easier and a slave was not missed so soon; in addition, a number of whites had gone to the church upriver.

The intention was to overpower the whites in as short a time as possible, and to take all the goods with them which could be of use, more especially guns and ammunition which together with the boats, the form of communication in the colony, constituted the main means to success.

The Uprising was so well set up that the plantations in the district between plantation Antonia and Peereboom joined in, either voluntarily, or in consequence of the arrival of people like Coffy and Accarra from Lelienburg, Atta from Altenklingen and Cossael of Oosterleek. In a very short period the revolutionaries had established a foothold where there were no whites and from where they could operate on two sides.

Collapse of whites

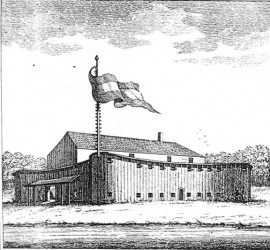

At the time of the Uprising Van Hoogerheim had only eighteen men in Fort Nassau at his disposal, military and burghers included, together with four ships waiting in the Colony for a return cargo. Van Hoogenheim took immediate action. He sent the slave ship Adriana Pitronella under Captain Kock up the river with instructions to drop anchor just above the plantations which had risen up, while the other three ships were placed in a line before the Fort. By this means Van Hoogenheim hoped to contain the Uprising within a small area, and to take the revolutionaries from two sides. This plan came to nothing as Kock dropped anchor before Plantation Zublislust, well below the plantations which had risen up, and where the whites were busily engaged in preparing for evacuation, since ensuring the safety of self and goods was considered by them to be of paramount importance.

Councillor Abbenzets had only a few members of the burgher militia at his disposal on Plantation La Solitude as most of them found it advisable to be downriver.

Furthermore, approximately forty whites from the area occupied by the revolutionaries had sought safety on the Company Plantation Peereboom. About six burghers had gathered on Company Plantation Markeij situated a little higher up. The following is from a letter from Mr Perrotet to Mr David Loofs in Amsterdam, in which the panic among the whites is clearly expressed. On the 27th February Perrotet had received a letter from Planter George, which he quoted to Loofs, and which ran:

“Dear Sirs and Fellow Burghers,

Today 4 plantations were destroyed by the rebelling slaves, to wit: the plantations Altenklingen, de Juliana, that of de Graaf and of Pieter van Staaden, on which most of the Christians were murdered. The Company Plantation Vlissingen is also in severe straits, shots are being fired one after the other; for that reason it is of the utmost necessity that each and every one secures his own plantation.

“Herewith commending Your Honour to the protection of God

My dear Sirs and worthy Burghers

Your humble servant

Joh. Chr. George.”

Perrotet then continued:

“The next day I again received a circular letter from our Burgher -Lieutenant Ch. Fr. Sejourne dated the 28th instant, which reads:

‘Dear Sirs and Fellow Burghers,

As our country is in dire need, I request [your] assistance and that you appear armed at the alarm post, the Company Plantation Markeij…

I remain,

in all haste

My dear Sirs and Worthy Burghers

Chr. Francois Sejourne.’”

After Perrotet had given these letters to his neighbour, Burgher-Captain Kunckler to read, the latter could say nothing other than, “My dear neighbour it is over for us and the Colony.” The following day he saw Kunckler passing by in a tent boat with his family and goods, leaving his slaves alone behind, among whom were some who had been newly imported. In any case, Perrotet did respond to the call, and arrived at Markeij on the 2nd March, where he learned that the burghers from Upper and Head Divisions had fled to Peereboom, as a consequence of which thirty plantations were already in the hands of the rebels.

Peereboom

On account of the panic and wait-and-see attitude of the whites, the revolutionaries could retain the initiative. Their main body was now concentrated on Peereboom. They attacked this place with such fierceness that the whites were compelled to come to an agreement with them; according to Perrotet, they were “about one thousand strong.“

According to Charbon, the son of the Manager of Oosterleek and one of those who had taken refuge at Peereboom, the initiative for negotiating an agreement came from the rebel side, in particular from Cossael of Oosterleek. A free retreat was included in the bargain, but when the whites got into the boats on the naïve assumption that they could go unhindered to the Fort, the rebels opened fire. Most of the whites were killed, although some did manage to escape, such as Charbon, who nevertheless fell into their hands a couple of days later.

As a consequence of this victory the revolutionaries gained control of the whole area above Fort Nassau, as the whites on Solitude and Zublislust in addition to those on Markeij were of the opinion that everything was now lost and their best course was to take flight. Those from Solitude and Zublislust fled to the Fort, but this route was closed to the whites on Markeij. There was only one possibility remaining to them, viz. overland to Demerara. The Moravian Brethren also went there from Pilgerhut in the Wiruni. It was only on the 17th April that Van Hoogenheim was informed in a letter from Storm van ‘s Gravesande, Governor of Essequibo, under whose jurisdiction Demerara lay, that the whites had already left the upper Berbice on the 5th March, As a result of this, the rebels could direct all their attention to the lower Berbice. Consequently, they moved in the direction of the Fort.

The revolutionaries released the captive pastor, Ramring, as well as his wife and her sister, who appeared at the Fort on the5th March. Van Hoogenheim noted in his Journal: “… the same [ie Ramring] had been charged by the two leaders of the rebels to convey a message to me, whereby they let me know the cause of what the Uprising was, namely, the cruel and barbarous treatment from a group of our inhabitants whose full names were given.” Was this an oral or written message? Possibly the latter might have been the case.

The confidence of the revolutionaries increased daily. They released Mrs Schreuder, who arrived at the Fort on the 8th March and handed a letter to the Governor which she had had to write for the leaders, stating:

“Warning to his Excellency Governor from Captain Koffie of Mr Barkeij and Accara also of Barkeij.

“His Excellency the Governor be warned that his Excellency should go with the ships to Holland as soon as possible, if not immediately and should the Governor not do this then your Excellency must fire three shots and then the Captain will come with a large number of people to fight.

“The reason for this war is that there have been many gentlemen who have not given the slaves their due, the principal among these being Barkeij, Jansen, De Graef, Isaack and Mr van Lendsing and we request that the slaves who are nearby should not be taken along or things will go badly.”

In other words, the revolutionaries were claiming the whole Colony as well as all the slaves, for even those slaves who were with the whites had to be left behind. Further-more, it is to be observed that the leaders were both giving explicit reasons for their revolt as well as indicating their aspiration for freedom since they also claimed that same freedom for the slaves who were with the whites.

The following remarks might be made with reference to these whites:- Van Lentzing was the manager of Plantation Antonia, while De Graaf was owner-manager of Hoogstraat. Barkeij was planter on Lelienburg, and Isaac Hermans was his employee. Although there is little explicit data on Berkeij’s life other than that he was born and brought up in the Colony, it may be that he was a typical example of what Van Lier has called the “psychopathic personality.”

Van Hoogenheim certainly commented on the fact that it was rather remarkable that the four most important leaders came from Lelienburg, although apart from Coffy and Accarra, we have not been able to establish to which four he was referring.

The government ignored this warning of the 8th March. On account of the recalcitrance of the skippers and burghers, the weakness of the garrison and the dilapidated state of the Fort, the whites decided to abandon it, set it on fire and retreat downriver. The rebels, who in the meantime had already set up an outpost on Vigilantie, not only fired on the ships floating down, but also succeeded in capturing those ships in which slaves had been placed. They shouted to the whites from the bank that they would come to fight them on Dageraad. This, however, did not happen, as Van Hoogenheim proved unable to keep the whites on Dageraad, and found himself forced to float further downstream to Fort St Andries. Not until the arrival of 100 men as relief troops from Suriname, who came into the Colony on the 28th March, did the situation change.

Organisation

Meanwhile the Negroes had set up a proper organisation. Co-operation was good; the differing African origins did not constitute an impeding factor. It appears from the various interrogatories in 1764, that a government had been formed that closely resembled that of the whites. They had a Governor who was assisted by a Council. Coffy from Lelienburg was the Govenor, and the Councillors may have been Accarra of Lelienburg, Atta from Altenklingen, Frans of Staaden, Berent from Zublislust, Nouakoe of Hollandia, and someone from the Company-owned Head Plantation.

There was also a Fiscal and a Hangman. It might be noted, however, that the membership of the Council probably changed over the period of the Uprising. The headquarters were initially established on Hollandia, where several whites were killed and subsequently their heads placed on stakes by the river side – a white practice in relation to slaves.

Various functions were divided among the people. In the interest of unity strict discipline was the primary requirement. For that reason those people who had either kept aloof or had assisted the whites in making good their escape had to continue to work as slaves on the plantations. The case of Jantje of Vlissingen can be cited as an example here. A couple of slaves from this plantation had taken their master to Peereboom. When the battle started, they were ordered by their masters to lie in a canoe beyond the reach of ball [ammunition]. However, the attackers sent them back to Plantation Vlissingen. After the battle on Peereboom, Coffy appeared on Vlissingen, and Jantje said: “Coffy said to them then, that since they wanted to help their master, they should now be slaves of the other people [rebels] and work for them, as they had had to do for the Christians.“

Why did Coffy do this? These people had to be kept away from the struggle as much as possible because of the likelihood that they might change sides, and would give the whites information concerning the position of the revolutionaries. Besides, they could ill-afford the loss of manpower. Although they had made themselves masters of the larger part of the plantations with their provision grounds, a regular food supply in the long term was not necessarily guaranteed. People had to be specially assigned to cultivation, and who was more suited for this than those whose opposition to the whites was not one hundred per cent certain.

Some slaves had to work the provision grounds, others had to keep the sugar plantations going. The slaves on West Souburg also had to continue to work as slaves. Some of them had to cut cane on this plantation; others had to bring the cut cane to Vlissingen, where the sugar was manufactured. From this it would appear that the manufacture of kilthum was not the sole object of the rebels, contrary to what most writers have claimed, but that Coffy, in particular, had rather more in view.

The impression is even given that Coffy had an inventory of the district drawn up, because according to Quassie of Savonette, Coffy sent Atta with his people to “have all the people and cows [there] counted”. These slaves also had to remain slaves and to make sugar, because they had not “cut off their master’s head.”

Coffy continuously re-distributed people around the different plantations. Thus he may have sent all the Loango people upriver to lay out provision grounds near Savonette. It is not clear exactly when this occurred. Furthermore, it cannot be established whether he always put people of the same nation together.

On each plantation he appointed an overlord or master who was in charge of administration on the plantation. Sometimes this was the former bomba , but on other occasions the bomba was killed or committed suicide. Those who had been active right from the beginning became soldiers. Also here, the resemblance to European titles is noteworthy. There were Captains, Lieutenants, Ensigns and Privates. They set up posts and used passwords.

Apart from that, they made use of spies who could keep them informed about the position of the whites. Sometimes rebels stayed behind specially on the plantations, in order to give information to these spies. In other words, it can be seen that the leaders had an eye to long-term planning, and that right from the start, everything was done to steer the Uprising in the right direction and leave nothing to chance.