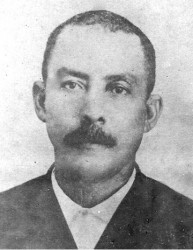

The month of June marks the centenary of the death of one of Guyana’s most talented nineteenth-century architects, John Bradshaw Sharples. We are told by his great grandson that he was very much a family man, and placed great emphasis on education. However, it is for his creative work in relation to Guyana’s wooden architecture that he is of course remembered, and in the following feature Clive McWatt writes about his great grandfather’s career, and describes the houses he built which still survive.

By Clive Wayne McWatt

The name Sharples is closely associated with Guyana’s wooden architectural heritage. The ‘Sharples House’ has almost become a term in the nomenclature to describe an architectural style of house building which was unique to Guyana. It could be described as a vernacular architecture of the late 19th century which evolved from local needs and construction materials, reflecting the environmental, cultural, technological and historical context of tropical Guyana. The eclectic design elements used in the buildings result from a

fusion of European building styles ranging from classical columns and architraves, neo-Gothic Victorian to Italianate Renaissance and Moorish decoration and carving. Sharples lived for short period in London in 1885-86, and from his abode in Bloomsbury, he would certainly have encountered Georgian town houses and Victorian Gothic revival buildings.

This year marks the centenary of the death of John Bradshaw Sharples, my great grandfather, the architect-builder and contractor, who died at his home in Middle Street, Georgetown on June 2, 1913. His express desire was to have his resting place in the ocean and this request was carried out in accordance with his wishes. On June 3rd 1913, The SS Parika steamed fourteen miles out of Georgetown into the Atlantic Ocean and the committal ceremony was performed. To quote Shakespeare’s Ariel, “Full fathom five thy father [JBS] lies…” but “Nothing of him doth fade…” in our memory of him; the houses which he designed and built one hundred years ago still grace the Georgetown suburbs, and remain an enduring legacy.

John Bradshaw Sharples was born in British Guiana on July 9, 1845, the son of James Bradshaw Sharples (1799-1859) of Lancashire, England. Very little is recorded of his father and mother; it is known that Sharples senior had estates at Golden Grove and Belfield and built the Leper Asylum at Mahaica. The youngest sibling was Daniel Sharples the renowned schoolmaster, who became Headmaster of St Thomas’ School in 1876 and held the post until his death. After the death of his first wife Helen Rebecca Scott in 1885, J B Sharples married her sister Marie Johanna Scott and between them they produced a progeny of ten. Two of his sons, Ovid and Gui Sharples became magistrates, while another two, Jack and Peter became medical practitioners; his eldest daughter Eloise Sharples succeeded James Rodway in 1926 in the post as Librarian and Secretary of the Royal Agricultural and Commercial Society in Georgetown; her sister Waveney Sharples, a civil servant, was also Chief Guider and Brown Owl.

After a career in the Royal Engineers, JB Sharples started his own business in 1880 ‒ the British Guiana Sawmill and Kingston Steam Woodworking Factory in Duke Street Kingston and Water Street. His woodworking factory was well equipped with the latest machinery which produced the fine craftsmanship in carpentry seen in his buildings.Venturing into building contracting, JB Sharples carried out possibly the largest contracts of that time, building all the railway stations, bridges, stores and other railway projects from Georgetown to Rosignol, some of which structures, such as the Georgetown Railway Terminus at Lamaha and Carmichael Streets, have since met their demise. He also built Bishop’s House in Kingston and it is believed that the house in Main Street Georgetown which was built for the D M Hutson, (now the Walter Roth Museum) was also a Sharples project.

I have highlighted here three of the better known examples of Sharples houses which were built over a century ago. The houses have undergone successive phases of alteration and renovation but they have still retained much of the original architectural design features and fabric.

The Queenstown House at the corner of Anira and Oronoque Streets, was referred to as the “honeymoon house,” perhaps because it may have been reminiscent of Swiss chalet design –

JB Sharples went to Neuchatel Switzerland in 1885 for his second marriage. The original house was raised no more than seven feet from the ground, which gave it a cottage-like appearance but the house has subsequently undergone many renovations and has lost its original proportions. Marie Sharples, his widow, lived here until her death in 1948 and various Sharples siblings resided here until the 1960s.

The House at 93 Duke Street was one of the earliest houses to be erected in Kingston, and the Sharples family lived there when it was first built. The decorative façade of the house once had Demerara shutters on either side of the casement windows. The steep pitched roof gable with decorative barge boards are some of the distinctive architectural features, along with the mouldings on the wooden cladding. Sharples employed distinctly classical elements in the design of the portico ‒ the entablature with a frieze of

animal and human figures is supported by clusters of columns crowned with Corinthian capitals of tight acanthus leaves.

The other Queenstown house, located in Forshaw Street, is an exquisite wooden villa set back in a well-cultivated garden. The symmetry in the façade has a measured rhythm created by the horizontal and vertical lines of the fenestration which incorporates glass casements and wooden louvred shutters and jalousies.

This rhythm is broken only by the wrought iron balcony which adds a delicate lightness to the façade. The ground floor rooms are set back to reveal the paired iron columns which create a loggia under the upper storey. Of all the three houses this has

retained much of its original character; it is well maintained and still exhibits most of the attributable hallmarks of quality craftsmanship to be found in the fabric of these Sharples designed houses. This house is featured in Georgetown’s architectural ‘heritage trail’ and normally gets the accolade as “The Sharples House.”

The Sharples houses continue to delight and charm those who see them and those who write about their status in the architectural history of Georgetown. These elegant urban villas exhibit what is an ideal for tropical domestic architecture. The house construction not only utilised sustainable building materials such as local timbers, but were also designed to maximize

natural ventilation and shade, so necessary in a tropical climate. Sharples created an aesthetic fenestration which integrated wooden shutters, Demerara windows and jalousies, French windows, iron balconies and steeply pitched roofs for rain water run-off; yet indulged in fantasies of design using carved wood mouldings and fretwork and wrought iron in applied decoration. Long may these houses continue to survive the vicissitudes of urban Georgetown.