A most unfortunate public exchange took place recently between the Auditor General and the Chairman of the Public Accounts Committee (PAC). The issue at hand was the Auditor General’s dissatisfaction with the pace of the PAC’s work. He went public but it is not clear whether he had raised the issue first with the PAC. Even if he had done so, and was not satisfied, it was inappropriate for him to publicly castigate the PAC and in particular the Chairman. This is especially so since he had quite rightly stated that the delay had nothing to do with him. By going public first, the Auditor General has crossed the boundary of his responsibility and into the realm of politics, given how divided the PAC is at the moment.

Relationship with the Legislature

What was more unfortunate was the statement the Auditor General reportedly made: “I refuse to accept that from Greenidge. You cannot tell me how to do my work.” Whatever statements were attributable to the PAC Chairman, the issue should have been dealt with in a more civilized manner. After all, it is the PAC that approves of the Audit Office’s annual work plan and budget; ratifies senior appointments; and exercises general supervision over the functioning of the Audit Office, including the functions of the Auditor General relating to the staff of the Audit Office. The Auditor General is also required to submit to the PAC quarterly and annual performance reports. Simply put, the Auditor General ought not to have made such a crude statement to the head of a committee to whom he has an administrative reporting relationship. He serves the Legislature and by extension the Public Accounts Committee of the National Assembly.

Need for the display of humility

The statement that “You cannot tell me to do my work” smacks of arrogance considering that the position of Auditor General requires the skills, competence and training commensurate with those of an experienced professionally qualified accountant with a proven track record. It is public knowledge that the Auditor General does not measure up to those requirements. As such, he should display humility if there are criticisms of his work regardless of how unjustified he may consider them to be, and learn from them. The most casual reading of his 2012 report would suggest a lack of due care in its preparation. Many of the findings were not properly developed in terms of criteria (what should be), condition (what has happened), cause and effect to support the related recommendations. The overall opinion on the financial statements was also incorrectly formulated and lacked the touch of professionalism. These apart, the Auditor General is yet to report on the expenditures on the Great Flood of 2005, the 2007 Cricket World Cup and the 2008 CARIFESTA X. He is yet to register concern regarding the constitutional violations in the operations of NICIL; the recruitment of some 20 per cent of contracted employees without the involvement of the Public Service Commission at salaries and other conditions of service significantly higher than employees in the traditional public service; and the non-functioning of the Public Service Appellate Tribunal and the Integrity Commission, among other critical areas.

While it is true that the Constitution provides for the Auditor General not to be subject to the direction and control of any person or authority in the exercise of his function, he has to be careful not to interpret this requirement in a manner that suggests that he is accountable to no-one. External auditors, the Auditor General included, cannot be directed as to what areas they are to cover; how they should conduct their reviews; and how to present their findings and recommendations. This is necessary to ensure the independence of the external audit function, free of interference from those whose work is being evaluated. Suffice it to state that audit independence is not an absolute concept.

The PAC is no different from an audit committee that acts as a go-between involving management and the external auditors. Given the knowledge and experience of members of audit committees, external auditors do benefit from their advice, especially in terms of areas that should be given priority and in the design of a programme of audit testing.

Responsibilities of the PAC

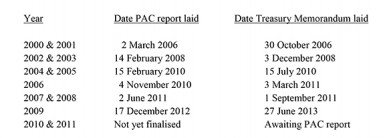

The Auditor General stated that the PAC was going through his reports paragraph by paragraph and that this was time-consuming. In the past, the PAC has been slothful is discharging its responsibility. However, the situation has improved significantly during the period February 2010 to December 2012 when reports for six years were finalized. This works out to an average of a little over five months per report, as shown below.

As regards the years 2010 and 2011, the Chairman explained that only the Ministry of Finance was left to be examined and that the draft report would be ready in six weeks’ time. He also indicated that members of the PAC are also members of other standing committees and that 2013 was a particularly difficult year in terms of scheduling PAC meetings, given the new configuration of the National Assembly and the priorities of the legislative agenda.

The Chairman further stated that there were other contributing factors and hinted that it was probably the intention of some to slow down the work of the PAC. This is an indication that all is not well with this important legislative oversight body that ought to put aside partisan political interest and function in unison to protect public resources and to ensure that they are used for the purpose(s) intended, with due regard to economy, efficiency and effectiveness and in conformity with the related laws, regulations and policy directives. One remembers clearly how divided the PAC was in relation to the ratification of 11 senior appointments in the Audit Office and what eventually happened when an Opposition PAC member was inadvertently absent.

Audit Office’s effectiveness

In order to maintain his impartiality and not be caught in the political fray, the Auditor General should refrain from making statements publicly on the work of the PAC. Comments such as “the Government takes my report seriously and I refuse to accept Greenidge’s comments” do no good to his impartiality and appear designed to pander to the Government. It must be recalled that the Government jumped to the defence of the Auditor General in relation to the conflict that has been existing between the Audit Office and the Finance Ministry since 2006, while the Auditor General remained mum on the matter.

The latest US Department of State’s assessment was that the effectiveness of the Audit Office’s work is adversely affected since the Government may or may not act on the recommendations of the Auditor General. The Auditor General himself acknowledged this when he stated that about 50 per cent of his recommendations contained in his 2011 report were yet to be implemented. So, does the Government take his report seriously?

Quality versus quantity

Sometime last year, the Auditor General invited me to a meeting with two consultants who were interested in formulating a communication strategy for the Audit Office. I made it clear that the Auditor General’s report was too long and that every audit finding, regardless of how immaterial it was, appeared to have been dumped into the report. There was no filtering to determine which ones would warrant the attention of the Legislature. As regards the physical verification of works, the results, whether they represent findings or not, were reflected in the report, thereby making it unwieldy and cumbersome. Emphasis was on quantity and not quality, and the report is devoid of editorial input.

Full reporting versus exception reporting

When we restarted the process in 1992, we engaged in full reporting of the results whether they represent findings or not, as opposed to exception reporting as is the established audit practice. This was necessary in view of the ten-year gap and the need at the time to apprise legislators of how major aspects of the budget were executed.

Upon my return to Guyana after my two year stint in Africa, I reflected on this approach and felt that it was time to report by exception, meaning only deficiencies or shortcomings should be reflected in the report. In this way, I was able to cut the 2003 report by more than half through a combination of exception reporting and deciding on what findings were material enough to bring to the attention of legislators and the public. Unfortunately, when I demitted office, full reporting was re-instated, thereby contributing significantly to the lengthy PAC examination. The PAC has to go through the Auditor General’s report thoroughly before it can produce its own report.

Haste to meet deadline

In reviewing the 2012 Auditor General’s report, one gets the impression that in the haste of meeting the 30 September deadline, the Auditor General did not have enough time to carefully go through the initial findings first with his officers and then with the concerned Ministries and Departments. Had this been done, many of the findings could have been satisfactorily resolved and hence would not have found their way in his report.

The problem is compounded by the absence of an organized system of internal audit at the larger Ministries to police the system on a daily basis. Had such arrangements been in place and evaluated to be effective, the Auditor General could have relied on them, thereby reducing the extent of his work in evaluating systems and procedures and testing transactions and balances. Many of his findings are in the nature of internal audit findings and should not have found their way in his reports.

To be continued –