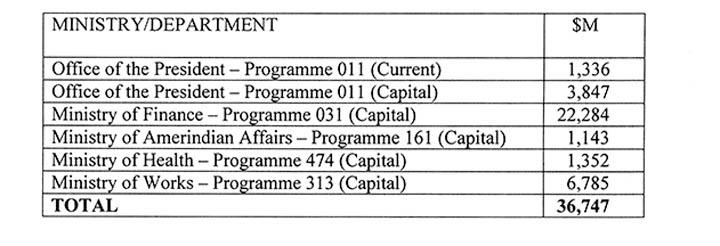

Hours before the deadline of 30 April 2014 for the Presidential assent to the Appropriation Bill that the National Assembly had approved in relation to the 2014 budget, Prime Minister Sam Hinds, in his capacity as acting President, signed the Bill authorizing amounts totaling $183.3 billion to be withdrawn from the Consolidated Fund to meet public expenditure. The Government had presented a budget of $220 billion but after the deliberations of the National Assembly, there was an overall reduction of $36.7 billion, as shown below.

Interpretation of the Chief Justice’s ruling

The Chief Justice’s ruling can be interpreted in two ways. The first is that the Assembly could approve or disapprove of the proposed budget in its entirety. This means that if it is dissatisfied with certain aspects of the budget, and the Administration is unwilling to address them to the Assembly’s satisfaction, the only course of action is to reject the entire budget. If this happens, there will be a constitutional crisis since no funding will be available to meet essential services of the Government. In the circumstances, Parliament will have to be dissolved and fresh elections called within three months. Fortunately, this did not happen for both 2012 and 2013, as the Administration made the necessary amendments to the related Appropriation Bills to take into account the Assembly’s decision to reduce the budget. Despite this, the Administration chose to seek the intervention of the Court as regards reductions made in 2012.

In a previous column, I had suggested that inasmuch as the Assembly may have concerns about certain items of proposed expenditure, it should nevertheless approve of the budget in its entirety to conform to the Chief Justice’s ruling. The Assembly can then apply the provisions of Article 172(2) of the Constitution to reduce the charge to the Consolidated Fund in order to address its areas of concern. That article precludes the Assembly from proceeding with a Bill or a motion that, among others, imposes a charge on the Consolidated Fund or any other public fund, or for altering any such charge otherwise than by reducing it, without the Cabinet’s consent (emphasis mine). In other words, it is permissible for a Bill or a motion to be introduced to reduce a charge on the Consolidated Fund without the approval of Cabinet. Any such Bill or motion, however, must relate to an existing charge and not to a proposed charge (emphasis mine). The Assembly could therefore apply this provision that has the same effect as disapproving expenditure with which it is unhappy. This approach obviously raises important questions about the appropriateness of the Court’s ruling.

The second interpretation is that since the Assembly considers the budget on a programme basis, it could disapprove of particular programmes if its concerns have not been adequately addressed. The Assembly has taken this approach in its deliberation of the 2014 budget and did not approve of the six programmes referred to above. In so going, however, essential services contained in these programmes have been adversely affected. For example, under Office of the President (Programme 011), the entire programme amounting to $5.183 billion was voted down because of concerns relating to the operations of Government Information Agency (GINA) and National Communications Network (NCN). This “collateral damage” is the cost of administrative services of the Office of the President as well as subventions to other agencies with a reporting relationship to it, the Institute of Applied Science and Technology being one of them.

The Administration knew full well about the Assembly’s concerns about GINA and NCN (Office of the President); the Amaila Falls Hydro Project (Ministry of Finance); the Specialty Hospital (Ministry of Health) and the Cheddi Jagan International Airport, Timehri (Ministry of Public Works) because in the preceding two years the Assembly had voted down these items. It was a foregone conclusion that the Assembly would do so again, given that its concerns remained unresolved. The combined Opposition had pleaded with the Government to separate these items out so that the other items within the five programmes could enjoy smooth passage. Regrettably, the Administration refused to do so and appeared to have dared the Assembly to do what it did. Who is to blame?

While many may want to consider his ruling as having contributed to the present dilemma, the Chief Justice did advise that in view of the new configuration of the Assembly and order to overcome any disagreement, it would be appropriate for the Minister to rework the budget instead of the Assembly. Unfortunately, the Minister did not follow the Chief Justice’s advice and continued to integrate contentious items with those relating to essential services.

What should the Assembly do in these circumstances? The argument that this was exactly how the budget was presented in the past is no justification for a continuation of this practice in view of the Chief Justice’s ruling. In the end, the Minister amended the Appropriation Bill to bring it in conformity with the wishes of the Assembly. He could have done so in respect of the contentious items thereby saving the day for the approval of the essential services contained in the contentious programmes.

The budget process for 2014 began since July 2013, but the Administration did not engage the combined Opposition in any meaningful discussion in the crafting of the budget. Commonsense would dictate that this should have been so, given that the combined Opposition now has control of the Legislature. Had the Administration engaged the Opposition in a meaningful way and in the spirit of goodwill and compromise, the nation would have been spared of what it had to endure over the last few weeks. After all, the combined Opposition represents 51 per cent of the electorate compared with the Administration’s 49 per cent which makes it a minority government – hence the need to have meaningful consultations with the combined Opposition.

Amerindian development

The Assembly did not approve of $1.143 billion representing the capital programme for Amerindian development on the grounds that much of the funds was not used for the purpose intended but for political purposes that favour the ruling party. In particular, there are allegations that some Amerindians were being paid $30,000 per month from funds allocated under this programme to conduct party activities. In 2012, the programme received $211.5 million in funding. That figure increased to $934.1 million in 2013 or over 400 per cent.

The way forward

In order to restore the essential services affected by the decision of the Assembly to disapprove of the six programmes referred to above, it would be appropriate for the Minister of Finance to make withdrawals from the Contingencies Fund to meet the cost of the essential services. However, it would be advisable for him to first consult with the combined Opposition so as to avoid a situation where the Assembly would disapprove of any expenditure when the related supplementary estimate is presented.

Of course, recourse to the Contingencies Fund should not be made to cover expenditure for the entire year, and therefore a supplementary estimate needs to be presented to the Assembly as soon as possible.

The combined Opposition has indicated that it would have no problem with such an estimate.