Part 2

By Tarron Khemraj

Introduction

Part 1 of this essay argued that the main motivation driving private investments under the Jagdeo-Ramotar dispensation is the desire to use political power for the purpose of expropriating economic and investment opportunities for associates of the ruling party. The oligarchic economic regime manifests itself in illogical investments in hotels in the city, domination of the TV, radio and print media, unnecessary expansion of the airport terminal (at this time), secret use of taxpayers’ monies in investments, no transparent feasibility studies, foreign investors with no track record, secrecy in sharing out of rights to extract natural resources, weakening of local governance, wastage of limited financial resources and no good-faith consultation with the opposition.

The government understands that it must get the masses to take their minds off the daily troubles and challenges – such as high cost of living, killer mini buses, recurring floods, mosquitos-borne diseases, persistent blackouts, traffic jams owing to poorly planned infrastructure, bandits, pirates, horrible policing, poor healthcare, poor education delivery at primary, secondary and tertiary levels (University of Guyana is dying slowly) and many other ills – they face. The government, therefore, promotes entertainment industries as a way of helping the masses to be distracted from their everyday problems. Entertainment includes Main Big Lime, artless 20-20 cricket, gambling industries, lots of night clubs, ample rum shops and plenty party opportunities to wine up and down – what we term the “dem a watch we” development model.

Ad Hoc Development Strategy

The policy approach serves to maintain the Amerindians at subsistence level, just like the masses on the coastline. At subsistence, the marginal productivity of their labour will be just above zero. Low marginal productivity implies persistently low wages as petty services and the itinerant trader flourish. The newly rich living on the coast will blame the masses for being lazy instead of considering how their plutocratic policies have trapped most of the people in penury. The plutocrats will slowly divorce themselves from the essential public services shared by the masses. They will utilize the advanced healthcare systems of the Caribbean and North America, deliver their babies in the advanced economies, send their children to foreign colleges, and isolate themselves in gated communities with private security forces. The police force will be used as a spy agency, which enforces the economic interests of the plutocrats and wealthy criminals. Nevertheless, being economically abused, a large percentage of the masses will be grateful for the little handouts, the one bulb capacity solar panels, 20-20 cricket and opportunity to party.

There was never any consistency or comprehensiveness to the LCDS. In a sense, it’s one of the great swindles of our time. There is no attempt to link up a variety of renewable energy sources via a smart grid system. There is no focus on efficient vehicles, noise pollution, garbage pollution, beautification of the cities and rural areas, green public parks and bike lanes. There is no housing regulation to make sure private developers build homes that are energy efficient and optimize the Atlantic breeze as a cooling system. Little thought, if any, went into the road, water and drainage infrastructure of the new large-scale housing areas. Building codes are not enforced to preserve history like the historical district of Paramaribo. Bourda cricket ground disintegrates while the new stadium is transformed into the hot party spot. This should be no surprise since Freedom House has always argued that modern Guyanese history is only recorded in the West on Trial. Important institutions like NIS and UG, which the PNC had a crucial role in shaping, are allowed to disintegrate.

There is no discernible tax policy or exchange rate policy via social cohesion, which was the main variable preserving the fixed exchange rate regimes of most of the small island economies of the Caribbean. Distributional conflicts that sustain fiscal deficits and reckless monetary policy have been a major contributor to the weakening of the Guyana dollar over the decades, and the subsequent high inflation that this creates.

Private Investment Rate

The column will use the government’s own national accounts statistics starting from 2006. The year 2006 is important because the calculation was altered to take into consideration structural changes in the economy, thus rebasing the weights. As lamented many times in Development Watch, we do not trust the government’s macroeconomic statistics. Take for example the claim that per capita GDP is close to US$4000. We have argued that the low average growth rate since 1992 cannot account for the increase in the level of per capita income from 1992 to 2013. This implies Guyana is much poorer in terms of average income. Also, as was further lamented several times in this column, we do not have reliable sector statistics, unemployment data and data on labour force participation.

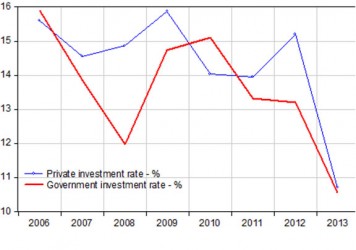

Nevertheless, let us take the government’s data as given. Figure 1 shows the rate of private investment (percentage) from 2006 to 2013. It also shows the rate of government investment as a percentage of GDP for the same period. The average rate for both time series is lower than the pre-2006 period. The downward trend in overall private investment continues from the previous Development Watch column that focused on this issue (See: SN Aug 12, 2009 “Slow fiah, mo fiah and the Guyanese growth stagnation”). Back in 2009, the column showed that the rate of private investments as a percentage of GDP continually declined from its highest percentage in 1992. The chart also shows a distinct positive association between the two series, thus being consistent with the argument that in post-Jagan Guyana the resources of the state are used to support oligarchic private investments.

Figure 1. Private and public investment rates (%) from 2006 to 2013

Years

Therefore, the overall economy is not doing as well as the government wants us to believe. The key argument of the column is the desire of the ruling class to control the business space is the crucial variable crowding out overall private investments. This is the phenomenon of oligarchic crowding out of overall private enterprise. Some businesses with the political monopoly rights no doubt are making money. But in the aggregate private investment as a percentage of GDP is declining. Only social cohesion can reverse these trends.

Comments: tkhemraj@ncf.edu