The Guyana Police Force cannot seriously believe that by publishing piece-meal quarterly statistics it is proving anything. It must know that one needs much more substantial and longitudinal numbers to be able to say anything meaningful about the direction of crime or about the efficacy of any policy.

If the following report is true, the absurdity of the comparison therein must be obvious. Indeed, in light of an experience I shall relate below, I sincerely question the conclusion.

“According to the police the strategies employed by the police force in dealing with crime, including ‘social intervention programmes with a focus on youths alongside intelligence-led enforcement operations,’ have impacted positively during the third quarter of the year when compared to the situation at the end of the second quarter!” (“Police credit strategies for third quarter drop in serious crime” SN: 11/10/2014).

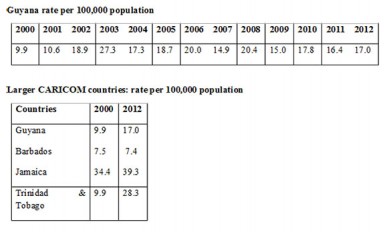

But with the exception of Suriname (6.1), Guyana has a smaller population than the other mainland South American countries and it is culturally more akin to the English speaking countries of the Caribbean. Therefore, it makes more sense to compare the situation across many years and in any number of ways, with these countries.

Over the period 2000 to 2012, the numbers have fluctuated for every country, but this limited comparison indicates that, with the exception of Trinidad and Tobago, the homicide rate has increased in Guyana more than in any of the larger countries. The figures also suggest that the homicide rate has still not returned to where it was before the so-called “crime spree” of 2002 to 2008. Indeed, Guyana tends to be second lowest only to Haiti (10.2) on most social indicators, homicide being a rare exception.

Many factors are said to account for the level of crime in a society. Generally speaking, the most constant of these are poverty and limited opportunities for the young. As with most social problems, although we may be able to identify many common factors, policies to reduce crime must be very country-specific. However, in our condition the regime’s contention that its “social intervention programmes with a focus on youths” have impacted positively on the crime situation, is extremely questionable.

Control over the forces of law and order is critical in any effort to establish and maintain political dominance. But in the ethnic context of Guyana, where Afro-Guyanese have traditionally and continue to constitute the majority of those employed in law enforcement, this can only be done in a manner that produces dysfunctional results and undermines efforts at crime prevention.

I have argued before that this dynamic has led to the PPP/C creating a permissive environment in the security forces. We have seen this played out with the shooting of protesters at Linden (“Minister Rohee and the Becket syndrome” SN: 01/08/2012) and with the Colwyn Harding case (“The Colwyn Harding case: A dysfunction of the politics of dominance” SN: 22/01/2014), where the police were accused of abusing a young Afro-Guyanese in their custody.

Indeed, on the basis of an experience on last Friday night at an East Coast night spot and inquiries made since, I suspect that on a daily basis in numerous places around Guyana, there are events which at least leave a perception of police harassment among Afro-Guyanese young people.

In a nutshell, on Friday 3 October 2014, at about 8.30 pm, friends and I entered a night spot. Music was playing and the DJ was enjoying himself, oblivious to the fact that in a few minutes he would be arrested by armed police and taken to the police station.

At about 9.15 pm, a police vehicle arrived and an inspector and a constable armed with a rifle came briskly into the premises and went straight to the DJ. In the crudest of manners, the inspector kept asking the DJ who had given him permission to play the music and telling the apparently reluctant constable to arrest the DJ, at the same time as attempting to dismantle the computer control from the music set.

The DJ was unsuccessful in explaining that the management had obtained permission for the music and as the inspector’s insistence that he be arrested continued, he without any resistance went with the policemen – who now had his computer in their possession – to their vehicle and was taken to the police station!

Even I, who am prone to give the police the benefit of the doubt, thought this action extremely heavy-handed.

But it was the general outburst of anger from the mainly young Afro-Guyanese gathering, both while the police were there and more so, after they left, that was telling.

The inspector being Indian, every possible racial, and administrative and other bias was directed towards Indians, the PPP/C government and the police. Such comments as “this harassment must stop; someone has to put a stop to this”; “he na no police, he from Freedom House” and “he (the DJ) gon come back just now: is money they want” were prevalent.

Whatever the merits or demerits of the police case (I was told that the management had received written permission from the commander of the region), the implications for policing and community relations were clear. A large swath of the population appears to believe that their community are being persistently and unfairly harassed by a police force that is politicized. The question is what can the PPP/C do to remove this perception and the answer is next to nothing!

The regime is caught in a structural condition of sub-optimality. Unless it wishes to share political space, as in most other areas of our lives, its efforts at crime fighting will be extremely restricted.

henryjeffrey@yahoo.com