Introduction

To be brutally frank upfront, without 1) strong independent trade unions pushing for national real minimum wage increases, the payment of living wages and the provision of substantial job programmes 2) a considerable strengthening of class-based ideology and politics among political actors and worker representatives 3) rising public awareness and consciousness (fuelled by public advocacy arising from evidence- based analyses), the struggle against grinding inequality and poverty in Guyana is as good as lost. The purpose of today’s column is to present the case in support of these blunt propositions.

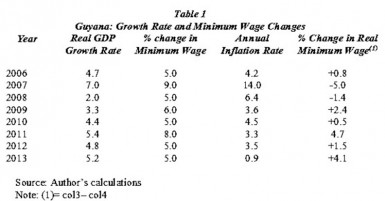

Table 1 displays key data illustrating the above propositions. Before examining these readers are cautioned that the time series displayed in this Table covers 2006-2013 only

On inspection the Table reveals that the annual increases in the nominal minimum wage paid to public employees during the period 2006-2013 has ranged from 5 to 9 percent, yielding a simple average annual increase of 6 percent. Further for 5 of the 8 years in that period, the increase was 5 percent. The peak years were in 2007 (9 percent) and 2011 (8 percent). The Table also shows the annual rate of inflation has ranged from a low of 0.9 percent in 2013 to a high of 14 percent in 2007 making it far more volatile than the rate of nominal minimum wage increases. Nonetheless, the simple average annual increase was approximately 5 percent. Finally, the annual “real” minimum wage change (that is the average annual nominal rate adjusted for annual price increases or inflation) is shown in the last column. The range for this has been from a low of -5.0 in 2007 to a high of 4.7 percent in 2011. The simple annual average increase over the period 2006- 2013 has been approximately one percent!

Minimum Wage Compression

Interpreting the information in the Table it is readily observed 1) over the period 2006-2013, the movement of the public employees minimum wage in real terms would have had a woefully negligible impact on improving the welfare of the lowest/ poorest sections of these employees and 2) with an outcome of less than one percent average net annual increase over 8 years this provides perhaps the starkest indicator of how unsuccessful were efforts to fight inequality and poverty. Indeed the observations expose 1) the objective weakening of the labour movement 2) the alarming success of government policy directed at subverting the wage negotiation process in the public sector and 3) because of limited public outcry, the dramatic retreat of even minimalist class-based perspectives in Guyanese politics and economics.

How the Minimum Wage Compares

At the end of 2013 the public employees’ minimum wage stood at G$39,540 per month. However, in July of that year the Government issued a National Minimum Order to cover all employees, both in the public and private sectors, equal to G$202 per hour, G$1616 per day, G$8080 per week or G$35000 per month. This is equal to approximately US$8.00 per day. If the HIES 2006 poverty line of US$1.75 were to be adjusted by the inflation rate cited in the Table, this would yield US$2.45 as an imputed poverty line for 2013.

This would therefore make the 2013 minimum wage about 3.2 times larger than the imputed poverty line for that year. Further, the per capita GDP for 2013 as cited in the 2014 National Budget was US$3496 or about US$9.60 per day.

There is growing support among United Nations agencies, led by the International Labour Organisation (ILO) in promoting the minimum wage as a strategic instrument in the fight against worldwide inequality and poverty. Thus in our region the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America (UNECLAC) has claimed: “the minimum wage can become a significant part of the solution to inequality”. Further, it observes that regional studies it has undertaken show that such wage improvements have had “no significant adverse effects on aggregate employment” despite the opposite claim of opponents. ECLAC goes further and states: “there is enormous potential for minimum wage policy to improve the income of the most disadvantaged; promote equality; and, strengthen internal demand”. In this way it can contribute to economic development.

Conclusion

Many Guyanese argue that the Guyana Government’s undoubted success in blunting the public sector wage negotiation process should be attributed to its effective” bribing” of public employees with its tactic of timely annual end of year or election- related pronouncements on wage increases. If true, the information cited in this column shows how paltry have been these bribes in real terms; averaging annually less than one percent over eight years! If true this brutally reveals not only a workforce lacking in self-esteem, but also the beaten down state of the trade union movement and its reduced militancy.

My own preference however, is to view the Government policy as being in single-minded pursuit of the injunction to conform to the internationally- driven agenda of severe wage compression in order to promote macroeconomic balance. This balance is viewed as necessary if not sufficient for Guyana’s growth and development. The organized worker movement has to take the lead in challenging such views if it is to contribute strongly to the fight against inequality and poverty. Unawareness and ignorance of the issues I have been raising in recent weeks are no longer acceptable excuses.

There are other very important considerations captured in the accompanying Table and many of these will be addressed in coming weeks.