Plastic City squatters are rapidly leaving the Best Village foreshore to build their houses after being granted land last year but a few who remain on the muddy garbage-strewn shore say that they cannot afford the price of house lots.

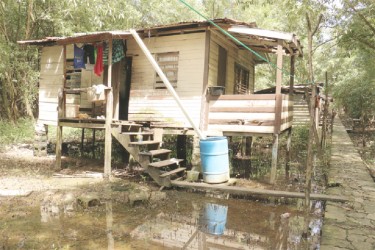

The squatting area is buried deep within a swampy forest of mangroves on the West Demerara, concealing old rusted zinc shacks and wood-patched houses. Cocooned in the thick swamp of mangroves, is a moss covered concrete pathway, leading out to the river.

For years, the villagers had cried out for relief from the sewage-filled water surrounding their homes and for running water and electricity. Some had said

that the Housing Ministry had collected their telephone numbers after they filled house lot forms but never got in touch with them. The others, who refuse to move, say that they want to remain and were hoping that the ministry would grant them land right there.

Lorene Cameron said that he has lived at Plastic City for 15 years and every time the place became flooded children would get sick. “We like this now but it isn’t long… it ain’t forever. We wouldn’t be like this forever,” he said. He is building a house at Parfaite Harmonie on the West Bank Demerara and it would soon be completed. “Things gon’ change. This ain’t forever,” he added.

pathway leads to a stone structure which the residents call the ‘First Baby monument’ at the end of the squatting area.

Susan Ramdas, who said that she had spent ten years living in the swamp, is also building her first home. She said she had received a house lot and would leave Plastic City as soon as construction is completed.

The 27-year-old lives with her husband and four children in a rusty zinc shack. “We don’t like living here. Who would? We only remain here because we can’t afford to rent a place,” she said, noting that her husband worked as a cane cutter and couldn’t afford much. “Money doesn’t easy here… Most of the men work and the women stay home and look the children. Mek sure that they go to school and eat,” she explained. “I didn’t choose to live like this. I have been living here since I was small. Me and my sister always wanted to leave and we did, but I came because sometimes there’s nowhere else to go.”

Her father, she said, died last year of pneumonia, leaving her mother to live alone and search for work. “We gon move though and mek a start,” she said, hopefully.

But for now she has to watch the skin of her children and other children along the concrete pathway break out with waterborne diseases and ringworms.

Shanta Ramdas, Susan’s mother said she was comfortable living in the swamp and that the “large” price of house lots was oppressive. “I can’t read and write so what type of job could I get to find the money to buy one? Not everyone fortunate, you know,” she said, adding that she was happy that her children would soon no longer be squatters.

Ramdas also said that she had no latrine and would use her neighbour’s as well as her neighbour’s bathroom. “Things rough in here. Children would still have to get up early in the morning and fetch buckets pon buckets of water to go school.,” she said, pointing out that young boys in the area would have to fetch the buckets of waters on their bicycles. “And if they don’t have that they would fetch it on their back.”

She lives in hope that one day they would be given light and potable water. “It’s really a strain to fetch water from till over on the train line,” she added.

Nazetta Gill, a 26-year-old who has lived in Plastic City for nine years, says she can’t afford any place better. “Our children don’t get to play after school because the ground is always muddy and dirty,” Gill told Stabroek News, while pointing to the yellowish-brown swamp that surrounded her home. She said that she was not happy with her living situation but stayed because she could not afford better. Planting, she said, was her hobby during the day before she moved to Plastic City. “I’m not happy here because I can’t plant anymore. If I try the spring tide would come in and kill them.”

She lives in a small patched house that has only one room. However, she happily stated that her husband was building a larger house a few yards away so that their four children would have a room to sleep in.

Squatters say that they are most affected in August when the water would rush onto the shore and flood the area, where it would eventually mix with faeces from latrines and settle around houses.

“This place isn’t healthy for people with children and everybody get children here,” a man said.

However, Ronald Alfred, who grew up in the area, said that he did not want to leave because Plastic City was all he knew. “I grow up here and I’m comfortable because we ain’t get nothing to be afraid of. No thieves,” he said but lamented that his major problem was getting running water.

“We just ga bare we chafe now, that’s all,” he said, adding that he enjoyed catching crabs when the spring tide came. Alfred has lived 19 years in Plastic City.

Avril Archibald, another resident, said that years had made people accustomed to the harsh life. “We accustom living in the area. Everyone already make their foundation. They tell us because we could make board house but not concrete,” she said.

She said that even though they were squatters they still deserved basic necessities like other people and pleaded for government officials to visit their area and assess the conditions they were living under. She added that officials from the Ministry of Housing had collected their numbers and promised to call but never did. “Some people moving out because they get through with them house lots but some of us still here and some of us want to stay,” she said.