Colin Bollers’ current business pursuits have their origins in skills learnt from his father who, as Chief Taxidermist at the National Museum, was tasked with the responsibility of preparing, stuffing and mounting the skins of animals for display.

Bollers also attributes the refinement of his own skills to what he says was the focus of the Forbes Burnham political administration on skills training, particularly in technical pursuits and in agriculture.

In 1976, he attended his first workshop in leather tanning at the North Ruimveldt Multilateral School and while, thereafter, he might have pursued the option of teaching, he opted to apply his skills to entrepreneurial pursuits and has been doing so for the past 38 years.

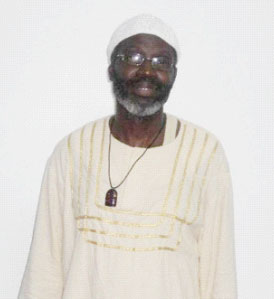

Named after his son and daughter, Joel and Trishelle, Jochelle’s Magnetic Craft, Bollers’ leather craft, and African fabric and natural products outlet is located on Merriman Mall.

Established in 1997, Jochelle’s was given its start following the accession to the mayoral office of Hamilton Green and the subsequent decision by the municipality to allocate part of Merriman Mall to street vendors. Bollers recalls that his startup cost was around $720,000 which was used to acquire the first consignment of skins, barks and chemicals used in the tanning process as well as an old refrigerator in which to store the skins during the tanning process.

Bollers’ pursuits in the business of leather craft go beyond simply earning a living. He is, he says, deeply concerned about the harmful effects of the wanton commercialization of leather craft and the often unsuspected health-related impact on consumers. More than that, he is mindful of the fact that the critical markets in Europe and North America have grown increasingly mindful of the dangers of disease associated with the unsupervised importation of goods that might be manufactured from inadequately processed skins.

It is this, Bollers believes, perhaps more than anything else, will continue to challenge Guyana’s ability to break into ‘the big time.’ He believes that over the years the quality of cow and sheep skins being made available for processing has declined continually. “The butchers don’t seem to recognize the importance of skins to the leather industry. Their emphasis is on producing meat. They take little care in removing the skins,” Bollers says.

More than that, Bollers points to difficulties associated with acquiring important raw materials used in the tanning process particularly mangrove barks. National regulations associated with adherence to the Low Carbon Development Strategy (LCDS) means that seasonal restrictions have been placed on harvesting of the barks.

The process of tanning itself requires equal measures of patience and skill. The skins must be preserved in generous quantities of cooking salt and left for several days after which they must be washed several times in order to remove meat residue, blood and dirt. The skins must then be placed in a lime solution in order to remove any hair and remaining flesh. Thereafter, they are washed again, pickled and placed in a tanning solution for between two and five weeks, depending on the thickness of the skins, and this completes the process.

Bollers’ considerable experience in the leather craft industry has made Jochelle’s a versatile producer of a range of goods and has won him a fair measure of popular patronage on the local market. His skills are also linked to the prestigious scroll holders used as cases for the credentials presented to holders of the prestigious Caricom Award. Bollers says proudly that pieces of his handiwork form part of the personal archives of several of the region’s leading luminaries including Guyanese-born former Commonwealth Secretary General Sir Shridath Ramphal, former Prime Minister of Jamaica P.J. Patterson, Belizean Prime Minister Dean Barrow, St Lucian Nobel Laureate Derek Walcott and two of the region’s most celebrated cricketers Sir Garfield Sobers and Brian Lara. And while his leather briefcases, passport holders, bags and wallets are known on the local market his success on the international market continues to be limited.

Bollers’ skills are also recognized in the region. In September 2014 he was commissioned to conduct a leather craft workshop in St Kitts for a group seeking to improve global marketability of leather goods produced in the region.

In 2012, mindful of the importance of broadening the range of the products offered by the enterprise Jochelle’s made significant additions to the range of goods which it offered the public. Responding to what it perceived to be a scarcity of African fabric and natural products on the local market the entity moved to fill the gap by importing a range of both fabrics and natural beauty products. The focal point of the beauty products is that they do not include the animal byproducts and possible ill health effects. The natural beauty products include African Shea Butter, black soaps, essential oils, natural hair products and toothpaste. Locally made natural deodorant and lip balm have also been sourced in Guyana, attracting a rapidly expanding market since their introduction.

Compared with other more conventional products, prices are reasonably affordable. Original black soap costs $1000; while African fabrics imported from Ghana by co-owner of Jochelle’s Miryom Levi cost $1,100 per yard.

Bollers is concerned that skills like tanning hides are yet to realize their fullest potential as far as providing employment options and growing enterprise are concerned. Accordingly, he talks of passing the baton, ensuring that his own skills are left behind with worthwhile inheritors. He told Stabroek Business that he is currently working on a project that seeks to train young people in the skill of leather craft. He is concerned too that bridges must be built between the meat industry and the tannery sector in order to reduce the wastage that occurs when meat is not skinned in such a manner as to ensure that skins are not destroyed. The leather industry, he says, offers some measure of promise as a means of employment and a possible vehicle out of poverty.

Whether or not his enterprise has been a success depends on the yardstick one applies. Bollers concedes that while he has few competitors some of them have secured an advantage arising out of their ability to source tanning materials abroad. Accordingly, they have access to higher quality leather. More than that, he admits to being equally preoccupied with the craft itself as with the enterprise. “I get a great deal of pleasure trying to get everything right. Sometimes, after a job is done I don’t want to sell it,” he says.

Bollers has not, over the years, embraced the mass marketing approach. He relies, he says, on the excellence of his custom-made designs and the preparedness of his customers to spread the word. Next year, he says, will see a determined effort to place his business on a firmer footing. Bollers says he is contemplating a shift from his custom-made creations to a wider range of products, increased volumes and, hopefully, more aggressive marketing.

He continues to face challenges associated with the quality of the leather with which he must work and concedes that this affects his ability to place his goods on a more demanding international market. That too has to change if his skills are to bring him real commercial success.