As part of the series on managing Guyana’s public investment regime, today’s column proposes a mechanism whereby our newly elected government could, at this unique democratic opening, embark on seeking bread (investible resources) and justice for Guyanese whose national wealth has been rapaciously plundered in recent years. This task is pursued in two stages. First, I demonstrate that, based on the data presented thus far in the series, together with the APNU+ AFC’s Manifesto referenced democratic dividend, the potential economic as well as governance returns arising from a moderately successful stolen public assets recovery initiative are significant and seemingly efficient from a cost- benefit and cost-effectiveness standpoint. Secondly, the practical steps government should take in pursuing this are suggested. As will be indicated, these steps derive from Guyana’s 2008 accession to the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). Before turning to these tasks, let me briefly address a hotly-debated and related issue of political morality.

Guyanese, broadly, support the view that the newly-elected government should neither misuse nor abuse state power in pursuit of witch-hunts against the rejected PPP/C political leadership. I share this view entirely. I am, however, equally convinced that this position would not condone a blanket or indeed other pardon for legally proven public corruption, ‘thieving,’ and plundering of the nation’s wealth over recent decades. More is at stake in this matter than the political preferences of the new government, which I expect it recognizes. A clear line must be drawn against past illicit/corrupt behaviours in order to prevent their future repetition. Furthermore, I shall demonstrate that, Guyana having solemnly signed on to UNCAC does not truly have legal discretion/choice in this regard.

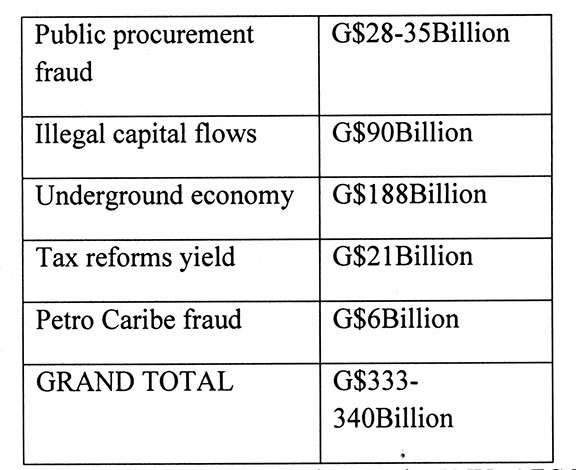

Pool of stolen public assets

For the democratic dividend (see APNU+AFC’s Manifesto, 2015) the Table lists only intrinsically corrupt public items that are additional to 1-3 cited above. These are: 4) tax reform gains, including from improved tax administration that constrains tax evasion and improves compliance. These are projected to yield a very modest additional $21 billion in total revenues, and 5) PetroCaribe savings arising from reduced illicit siphoning-off practices, $6 billion.

I emphasize here that I cannot provide independent valuation of corrupt practices in state enterprises. Nor have I provided independent estimation of what the APNU+ AFC Manifesto characterizes as: “the labyrinth of slush funds, parallel treasuries, and looted state funds exported to off-shore financial institutions.” The sum total cited in the Table although huge, $333-340 billion therefore understates the actual size of the pool of annual recoverable stolen public assets. What part of this clearly underestimated pool of stolen public assets might actually be recovered is open to speculation. However its huge size warrants careful evaluation. Thus, a modest ten per cent recovery rate, would yield about $34 billion or US$170 million, not counting its deterrent value against future corruption.

Public corruption on the massive scale revealed here cannot all be attributed to the PPP/C. It certainly embraces corrupt state officials and executives of state-owned enterprises, organizations, agencies and other bodies who have accepted bribes, sold influence, and generally pursued rent-seeking behaviours, as this notion was defined in last week’s column. .

Table 1: Estimated current annual pool of stolen public assets

Political capital

Because public corruption has been so widespread there is a political dividend available to the new government if, but only if, the APNU+AFC’s promise of good governance is substantially achieved in the coming years. This dividend is based on my estimation of popular expectations. Additionally, in losing the elections, the PPP/C loses control of state resources, which given its past performance in government, severely constrains its political mobilizing capacity.

How to proceed?

In this section, I briefly outline in simple steps the second stage of the task I have set for this column, which is, how best Guyana can proceed with its stolen public assets recovery program:

Step 1: Establish a public body dedicated to the initiative for recovering stolen public assets. Details about the likely composition of this body, scope of functions, legal structure, etc, will be addressed in next week’s column.

Step 2: Invoke Guyana’s responsibilities, duties and entitlements under the UNCAC. That Convention came into force in 2005. Guyana acceded to it in 2008. As it states “stolen public assets recovery is a fundamental principle of the Convention.” Further, all 175 UN members of the Convention have formally agreed to confiscate such assets returning it to the state requesting it, in order “to send a message to corrupt officials that there will be no place to hide their illicit assets.”

Step 3: The local body suggested at Step 1 should, as soon as practicable, formally request assistance technical and otherwise as is available under UNCAC, whose implementation is supported by the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime.

Step 4: Given the coalition origins of APNU+AFC, I would further recommend that civil society organizations, especially the internationally affiliated Human Rights Association, the local chapter of Transparency International, the Trade Union Congress, and private sector be encouraged to participate in the initiative, as presently permitted.

Conclusion

Because of space constraints, I shall have to leave until next week further elaboration of this highly abbreviated discussion of the practical steps Guyana should follow in the proposed stolen public assets recovery programme. The idea I shall stress there is that initiatives for recovery provide benefits in the form of preventing future abuses.