Introduction

Today’s column follows-up on 1) my earlier estimation of the value of potentially recoverable stolen public assets and 2) the ticking time-bombs that threaten the survival of sugar and rice. Item 2 threatens potential political economy benefits from both recovering stolen public assets and fulfilling government’s 100-day commitments. Additionally, as there was not enough space in last week’s column to comment on the situation with rice; I begin this today.

Illicit financial flows

My May 10 column indicated the 2014 value (and sources of estimates) for stolen public assets in Guyana arising from 1) procurement fraud ($28 to $35billion); 2) capital flight ($90 billion); and 3) the underground economy ($188 billion). This totals $308-$313billion, or about US$1.5 billion, representing about 52 per cent of 2014 GDP. I remain firm in the view that, if the new government staunchly commits to good governance, it could milk much of this for the benefit of Guyanese.

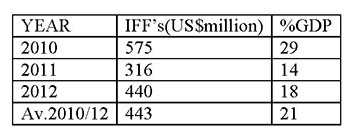

Estimated capital flight was sourced from Global Financial Integrity (GFI), which provides annual measures of Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) for 145 countries. The data I previously presented are reproduced in Table 1 below. They are obtained from GFI, and based on IMF databases containing official reports of international trade and balance of payments data provided by member countries. As indicated, while these flows constitute a major component of Guyana’s illicit capital flight, they do not account for its entirety. Yet, for 2010-12, their average annual value was as high as US$443million; compared to just US$83 million back in2003! Indeed, the 2003 value doubled to US$173million by 2006; doubling again to US$575million by 2010. Table 1 shows that, when expressed as a ratio of GDP, these flows fluctuated significantly, but averaged 21 per cent for the period 2010-12.

Table 1: Guyana’s Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) and % GDP

Source GFI, December, 2014 and Author’s calculations

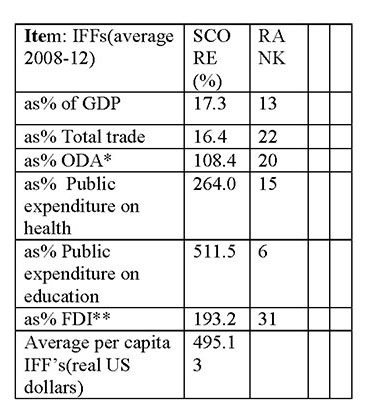

On June 4, a Guyana Human Rights Association press release reported the GFI had released the day before, a cross-country analysis of their December 2014 data covering 82 poor developing economies, including Guyana, which compared these data with key development indices for 2008-2012. For readers’ convenience, the schedule below displays the results of this comparison for Guyana, utilizing seven development indices and comparing these for the 82 selected poor developing countries. Schedule 1 displays Guyana’s score on each comparator, alongside its ranking within this group, where 1 represents the worst performer.

Schedule 1 Guyana’s relative performance (IFFs and development indices)

Source GFI, 2015; *= official development assistance; **= foreign direct investment

From a development perspective the data displayed add to the serious concerns economists hold about the under-development, which corruption and stolen public assets generate in developing countries.

Economic time-bomb sugar

Turning to the ticking economic time-bomb on which GuySuCo is perched; whether this is “politically triggered” with or without malice aforethought, its underlying dynamics plainly indicate an explosion in the not-too-distant future. Last week I had restated my long-held conviction that, at this stage of the long-term sugar commodity life-cycle in Guyana: “the industry had passed its tipping-point; thereby dashing hopes of an orderly reform and reconstruction”. GuySuCo has been producing over recent years, if not decades, less and less sugar at greater and greater unit and total costs, while its unit sale price has been declining. The logic of such a sequence is that GuySuCo has reached a point of no return. Going forward, it can remain open over the short to medium-term in only one of two possible ways. These are either through the provision of 1) regular direct official bailouts and/or 2) increasing borrowings and indebtedness, based on government guarantees. Clearly neither of these is sustainable, given GuySuCo’s present indebtedness, which already exceeds $90 billion and is projected to remain at this level through 2017.

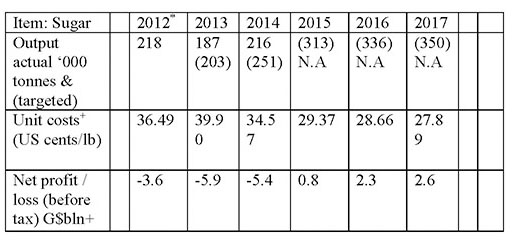

Other data provided in Table 2 below confirm this distressing picture of GuySuCo at great risk. Thus, in recent years sugar output has been at its worst levels in four decades. It produced on average 310-320 thousand tonnes of raw sugar back in the late 1960s to early 1970s with fewer assets. Moreover, its present day unit production cost, at 39.90 US cents per lb in 2013, has been rising, even though GuySuCo had projected in its Strategic Plan 2013-17 a decline from this year. Indeed, unit cost has been frequently about three times the world price of raw sugar. Not surprisingly therefore, net profit before tax has been negative through 2014, even though GuySuCo had, in its plan, projected a return to profitability this year; this is obviously impossible.

Table 2: Sugar at great risk

Sources: GSP Estimates, 2013-14 and BoG 2014. Note *= Guysuco unaudited management accounts; += projection for 2015-17; and N.A = not available

Ticking economic time-bomb: rice

Paradoxically, if as argued last week, the sugar commodity life-cycle for Guyana is in long-term decline, rice has been in a marked upswing. Contrarily, the ticking time-bomb that rice is perched on is due to 1) its explosive growth of output; 2) increasing difficulty in finding lucrative markets; and 3) the level of unit production costs. Rice output has grown explosively in the 2010s, rising by more than 100,000 tonnes annually since 2012.

Much of this expansion has been fuelled by government support to both supply (production) and demand (finding lucrative markets). As is common knowledge, the Venezuelan market is at great risk generating a potential demand/supply market imbalance. This imbalance risks a collapse of rice and paddy prices later this year, thereby impairing livelihoods, in contrast to what prevailed in the first half of the 2010s.

I shall pursue this follow-up further next week.