It is always of infinite interest to take a close look at trends in theatre in Guyana while casting a glance across the Caribbean to see how they measure up. The most recent stimuli for another analysis of these trends and developments have been the performances in Guyana of ‘50 Shades of Dance’ by the Classique Dance Company and ‘Nothing to Laugh About 8’.

These are very popular box office successes which now command serious attention because of their immense popularity, appeal and the place they have claimed in the local theatre.

Both have made significant advancements and can demand the acknowledgement of some achievement in their fields. They may also be evaluated in the context of what has been taking place out in the Caribbean.

One identifiable factor is that theatre in Guyana is still very conservative with many of the taboos, inhibitions and prohibitions still holding on from the colonial type theatre. Guyana has neither broken out of that epoch nor broken into the post-modernist or avant-garde advancements on stage seen elsewhere. The theatre of realism or naturalism still dominates.

Yet, Guyana is ahead of many other territories like the Eastern Caribbean and might have a busier year on stage than Barbados. While the rise of the popular theatre is one area in which Guyana lagged behind by more than a decade, it is in that very arena that it can claim some victories.

Tours by Guyanese companies to the Eastern Caribbean are infrequent, but when they happen their impact shows that that kind of theatre is insufficiently provided in the host countries. A recent tour to Antigua by Darren McAlmont’s Snapped, directed by Sheron Cadogan-Taylor revealed this, with little notable development in that island since Guyana’s Theatre Company went there.

The popular theatre in Guyana firmly reflects Caribbean trends at the present time. The ascendancy of Lyndon Jones Productions, the company now responsible for ‘Nothing To Laugh About’ is a case in point. Its annual staging of ‘Uncensored’ has cornered the market with a fixed place on the theatre calendar and guaranteed box office returns. Its brand of stand-up comedy is in demand and is in keeping with current Caribbean trends.

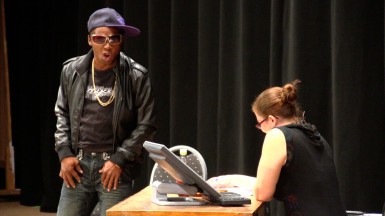

‘Nothing To Laugh About 8’ was directed by Lyndon Jones and attracted a cast of many of the leading comic performers in the country, not to mention the multitudes that make up the popular audience.

The annual production was originally created by Maria Benschop before she joined forces with Jones and that partnership has seen prosperity as a touring company with two exceedingly popular annual comic shows – this one and ‘Uncensored’. From a production with several serious problems of technical quality, it has grown considerably to be where it is now – with tours to different parts of the country and Georgetown audiences that fill the house every time.

It is a series of skits with farce, slapstick and an over-abundance of political comedy. The political humour made no pretence at being balanced or non-partisan, which on the one hand delighted crowds, but on the other is a limiting factor.

There was much improved technical management, stage use and fluency, with actors well inducted into the necessary comic performance style and delivery. The scripts were mixed – some sharp, some hilarious, others laboured towards damp punch-lines, a high level of repetitiveness but overall strong direction by Jones and effective performance.

Another feature that loaned strength to ‘Nothing To Laugh About’ was the way it has commandeered the popular selling points of a number of actors and actresses who have developed trademarks. These include Michael Ignatius, Leza Singh, Mark Kazim and Kirwyn “Sir” Mars. They have won audiences with these as stand-up comedians and brought them over into other stage drama.

Singh demonstrated a bit of versatile adaptability in her role as Radika for which she was beginning to attract some criticism. She once again showed her remarkable ability to win the audience and to get away with race jokes. Kazim has made a popular trademark of racial stereotyping from which the show also benefited, but the presentation of the Amerindian in the skit about the US visa went dangerously close to ridicule and ‘othering’ of a racial minority.

This employment of popular trademarks is a Caribbean trend in comedy. It has been responsible for much of the success of Jamaicans such as Oliver Samuels and has rocketed others like Shebada to stardom.

Not only stand-up comedy but stage plays have made use of it, with several plays being particularly written to include the character and his farcical antics. This also includes the way acts are stretched and played out to exploit audience interaction.

While the ascendancy of comic performance is a fixed trend across the region for drama and popular plays have a certain dominance, the popular theatre of dance has not been quite so wide-spread. In Guyana with the proliferation of new dance companies and schools the audience factor has become more of a deliberate focus. We have seen it reflected in the offerings of the National Dance Company, but it has become a major preoccupation of the Class-ique Dance Company led by dancer, choreographer and manager Clive Prowell. This group has helped tremendously to popularize dance in Guyana and to forge a new audience for the art form.

The colonial theatre was mentioned above, and the trends in dance in Guyana have certainly progressed well away from what obtained there. There has been a diversification in the offerings and a need to survive which drives an interest in box office returns. Popular dance has therefore developed considerably and brought in a very important change in the audience for dance – a new mass audience similar to what happened with drama.

Classique’s ‘50 Shades of Dance’ directed by Prowell continued and intensified that drive. It began with the title, continuing the use of sensational titles by Classique all towards the same purpose.

The title, of course, borrowed unashamedly from the book and film 50 Shades of Grey that stirred up such a storm in sensationalism and popularity recently. That alone would have got the attention of the popular audience. Then they would have been attracted by the prospect of getting more of what they have become accustomed to from Classique – their new brand of popular, unconventional and uninhibited dance.

Classique seems still to be interested in convincing everyone that they are competent in the standard forms of dance, in genuine proficiency and technique and in classical dance. They go out of their way to ensure the inclusion of a number of pieces of that calibre, even to the inclusion of the National Dance Company as guest performers in the show and they contributed to moments of calm command which included pieces by Classique. In all of this, Prowell, a product of the NDC, has grown in stature.

However, the show reveled in the outrageous, the unconventional and attempts at the cutting edge. Very important to these styles of dance is the popular culture and many pieces by Classique draws on it for audience appeal as well as for the integrity of some dances that are set in that cosmos.

This included the arrival of one of those trendy power bikes in the theatre and its contribution to a dance-hall styled choreography. In many ways some of the dances were not just gimmicky but genuine artistic attempts to recreate the mood and atmosphere of the social ethos captured in the dance.

At other times there is the pop culture emanating from some of the popular songs and a kind of psychological if not psychiatric state into which characters in the choreographies often found themselves. In those cases Classique set out to probe the mind while going for thrills of eccentricity. Other offerings were much less interesting, being mainly physical and acrobatic, sometimes demanding trained skills, but lacking intellectual excitement.

The most exciting thing about ‘50 Shades of Dance’ was its exhibition of a strong company of dancers obviously well trained and showing signs of versatility to match virtuosity.

It was the high octane energy generated on stage and reciprocated by the audience. But most important was the now settled trend of the creation of new non-middle class audiences, not always proletarian but definitely driven by youth. This group is populous as well as popular and has responded to the imposition by the Classique company of disciplined training and the imagination upon the anarchy, the restlessness in the mind of youth and putting choreographic shapes to the shapeless indiscipline of contemporary modern society.

Note:

I apologise for an error in the naming of a poet made in the Arts on Sunday account of Guyana’s Pre-Indepen-dence and Colonial Literature in our issue of Sunday June 14, 2015. The poet referred to is Simon Christian Oliver, and not Francis Williams as stated in the article.

Simon Christian Oliver was a schoolmaster in Buxton, Guyana who was a quite prosperous and educated free Black. He was one of the prominent local poets in British Guiana in the nineteenth century, famous for his poem in 1838 in celebration of Emancipation. That poem, however, is quite decidedly part of the colonial and imitative literature of the time, a poem more in praise of the queen and a salute to colonialism than one affirming the end of slavery.

Another prominent local native nineteenth century Guianese poet was Thomas Don (discussed by David Dabydeen in the Selected Poems of Egbert Martin).

Francis Williams (1700 – 1774) was a free Black in Jamaica sent to England, it is believed to Cambridge University, as an experiment to see whether slaves or Blacks were capable of ‘culture’ and education (the “noble savage” concept). Williams was successful, returned to Jamaica, worked as a schoolmaster and wrote Latin odes, as well as verses in praise of governors. He is said to have proven that the illiteracy among the Blacks was due to lack of opportunity rather than to incapacity.