Garber to fellow policeman: “You won’t believe this.”

Garber: “They took Pelham 123 today.”

Policeman: “I don’t believe it.” – From the film The Taking of Pelham 123 (1974)

I didn’t believe it either when I learnt that mankind had developed a machine which played chess. The news appeared to be within the realm of science fiction that reminded one of Isaac Asimov’s surreal short story I, Robot. The notion of a chess-playing automation, currently known to the world as a chess computer, was unbelievable because it ominously suggested that a chess machine such as the one devised, possessed the capability to think, much like Asimov’s robot. The concept defied logic as we knew it.

The idea of a chess machine was divulged in the year 1770. A fake machine named ‘the Turk’ was constructed and unveiled in that year by a German national apparently to impress the Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. The mechanism appeared to be able to play a game of chess with a human opponent. The Turk was in fact a mechanical illusion that allowed a human chess master hiding inside to operate the machine. The Turk won most of its games for its 84 years of operation throughout Europe and America. Statesmen like Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin opposed the Turk, which was destroyed by fire in 1854.

During the second half of the 20th century, computer chess became a startling and serious reality, unlike the delightful days of the Turk. The world was put on notice in 1989 when the IBM chess monster Deep Thought challenged the world champion Garry Kasparov to a two-game, fast-play match. Kasparov dispatched the computer with élan. The IBM team of chess grandmasters and computer scientists however, banded themselves into a unit and challenged Kasparov once again in 1996. He won comfortably, but this time the IBM chess computer now renamed Deep Blue, took a game from the world champ. The victory by Blue was unprecedented. It was the first time ever that a machine had defeated a world champion in a chess game under tournament conditions. The following year, in 1997, Deep Blue stunned the chess world when it toppled Kasparov in a revealing match victory. The inexorable march of artificial intelligence was alive.

In draughts also, the world’s strongest humans are no match for the leading programme. Chinook, for example, defeated Ron King, the Barbadian World Draughts Champion a number of times in a number of games. It owes its strength to a very deep look-ahead and an enormous database of endgame positions.

Kasparov did not succeed in obtaining a rematch following his loss at the 1997 competition with Deep Blue. The machine was retired to the Smithsonian Institute in Washington, DC. The initial idea was to overwhelm a human world champion and it did so efficiently. News reports indicated that IBM benefited from approximately US$500 million in free advertisements, and the company’s stocks surged by $10 after the match.

In year 2000, when Kramnik defeated Kasparov for the title, negotiations for a match began between the world’s strongest computer programme and the world champion. A computer chess tournament was held which decided the two finalists, Junior and Fritz for a 24-game match. At the conclusion of game 14, Junior, programmed by two Israeli chess scientists, boasted an almost unassailable lead of 5-0. However, the highly improbable does occur; Fritz snatched the match away from Junior by winning the final game and thereby qualifying to challenge the world champion. That match ended in a 4-4 draw.

The Deep Blue project inspired a similarly grand challenge at IBM: building a computer that could beat the all-time champions at Jeopardy! Over three evenings in February 2011, the machine named ‘Watson’ opposed two of the most successful human players of the game and beat them in front of millions of television viewers. The technology in Watson was able to process and reason about natural language. Perhaps Watson was demonstrating that a new generation of human-machine interaction was indeed possible.

Chess games

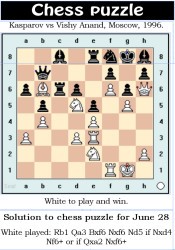

Here are the first and final games of IBM’s Deep Blue 1997 match with World Chess Champion Garry Kasparov. Kasparov lost the six-game match by a margin of 3.5 points to 2.5 . The other two games are taken from the 43rd Dortmund Sparkassen Chess Meeting which ends today in Germany.

White: Kasparov

Black: Deep Blue

Game 1

1. Nf3 d5 2. g3 Bg4 3. b3 Nd7 4. Bb2 e6 5. Bg2 Ngf6 6. O-O c6 7. d3 Bd6 8. Nbd2 O-O 9. h3 Bh5 10. e3 h6 11. Qe1 Qa5 12. a3 Bc7 13. Nh4 g5 14. Nhf3 e5 15. e4 Rfe8 16. Nh2 Qb6 17. Qc1 a5 18. Re1 Bd6 19. Ndf1 dxe4 20. dxe4 Bc5 21. Ne3 Rad8 22. Nhf1 g4 23. hxg4 Nxg4 24. f3 Nxe3 25. Nxe3 Be7 26. Kh1 Bg5 27. Re2 a4 28. b4 f5 29. exf5 e4 30. f4 Bxe2 31. fxg5 Ne5 32. g6 Bf3 33. Bc3 Qb5 34. Qf1 Qxf1+ 35. Rxf1 h5 36. Kg1 Kf8 37. Bh3 b5 38. Kf2 Kg7 39. g4 Kh6 40. Rg1 hxg4 41. Bxg4 Bxg4 42. Nxg4+ Nxg4+ 43. Rxg4 Rd5 44. f6 Rd1 45. g7 1-0.

White: Deep Blue

Black: Kasparov

Game 6

1. e4 c6 2. d4 d5 3. Nc3 dxe4 4. Nxe4 Nd7 5. Ng5 Ngf6 6. Bd3 e6 7. N1f3 h6?? 8. Nxe6 Qe7 9. O-O fxe6 10. Bg6+ Kd8 11. Bf4 b5 12. a4 Bb7 13. Re1 Nd5 14. Bg3 Kc8 15. axb5 cxb5 16. Qd3 Bc6 17. Bf5 exf5 18. Rxe7 Bxe7 19. c4 1-0.

White: Georg Meier

Black: Vladimir Kramnik

1. e4 e5 2. Nf3 Nc6 3. Bb5 Nf6 4. O-O Nxe4 5. Re1 Nd6 6. Nxe5

Be7 7. Bf1 Nf5 8. Nf3 d5 9. d4 O-O 10. c3 Bd6 11. Bd3 Nce7

12. Nbd2 c6 13. Nf1 g6 14. h3 Kh8 15. Bd2 f6 16. Qc2 Bd7

17. b3 Rc8 18. Re2 b6 19. g4 Ng7 20. Rae1 c5 21. dxc5 bxc5

22. Qc1 Bc6 23. Bf4 Ng8 24. Bg3 d4 25. N1h2 Bxg3 26. fxg3 g5

27. Be4 Bxe4 28. Rxe4 Qd6 29. Kg2 f5 30. Re5 h6 31. Qd2 Rcd8

32. Qd3 f4 33. Nf1 Qc6 34. cxd4 cxd4 35. R1e4 fxg3 36. Nxg3

Nf6 37. Rxd4 Ne6 38. Rxe6 Rxd4 39. Qxd4 Qxe6 40. Qxa7 Rc8

41. Nf5 Qe2+ 42. Qf2 Qd3 43. Qd4 Rc2+ 44. Kg1 Rc1+ 45. Kg2

Qc2+ 46. Kg3 Qc7+ 47. Kg2 Rc2+ 48. Kg1 Rc6 49. Kf2 Kh7 50. Ke2

Rc2+ 51. Ke3 Rxa2 52. Qc4 Qb7 53. Qe6 Nd5+ 54. Kd4 Qb4+ 0-1.

White: Wesley So

Black Arkadij Naiditsch

1. d4 Nf6 2. c4 e6 3. Nf3 d5 4. Nc3 Nbd7 5. e3 Be7 6. b3 O-O

7. Bb2 b6 8. Bd3 Bb7 9. Qc2 c5 10. cxd5 exd5 11. O-O a6

12. Rfd1 Re8 13. Rac1 Bd6 14. Bf5 Rc8 15. dxc5 bxc5 16. Qd3

Rc7 17. Na4 Qe7 18. Qc3 d4 19. exd4 Bxf3 20. Qxf3 cxd4 21. Ra1

Ne5 22. Qh3 g6 23. Bd3 Nd5 24. Bxd4 Nxd3 25. Qxd3 Nf4 26. Qxa6

Qg5 27. g3 Ne2+ 28. Kf1 Qg4 29. Be3 Rxe3 30. Qa8+ Kg7 31. Rxd6

Re4 32. Kg2 Nf4+ 33. Kg1 Nh3+ 34. Kg2 Rc2 35. Rf1 Nf4+ 36. Kg1

Qf3 0-1.