On weeknights the vendors show off their fruit and vegetables on both sides of Robb Street between Alexander and Bourda streets—huge piles of mostly freshly reaped callaloo, okra, bora and tomato and an assortment of fruit in season—their stalls attended by groups of family members and helpers carefully divided into those who handle the display and the others who interface with the customers.

The closeness, the proximity to each other coupled with the fact that they almost offer near identical goods for sale creates the impression of impracticable competition. Hardeen Singh, one of the vendors who has been trading in front of Chase’s Indigent Home on Robb Street for the last 11 years is quick to provide assurances that that is only an illusion. The vendors all have their own customers, bonds of patronage having been formed by mutual loyalties that yield knock-down prices and what is known in the language of the market as ‘mek-up.’

On Wednesday afternoon, Singh had his hands filled. He was offering for sale, okra, boulanger, tomato, squash, carilla, sweet and hot peppers, coconut and watermelon. He was part of a clutch of vendors who come from Parika, Linden, the East Coast and further, all of them wholesale vendors and all of them allowed to ply their trade strictly between 16:30 hrs and 07:00 hrs. The timing conforms to an arrangement that allows the vendors inside the Bourda vegetable market to be spared the competition from these wholesaler vendors.

Singh sells at the market on Sundays, Wednesdays and Fridays. On other days he is buying produce, mostly from the Corentyne. His is a typical example of a family vending enterprise. His wife works at the market with him and there is a rotational arrangement with his parents who attend to the business of selling on his off days from the market. This has long been the family’s way of making a living.

Market vending, Singh says, has its own challenges. Aside from the ebb and flow of business, there is the fact of the often uneasy relationship between the vendors and the authorities, more specifically the municipal constables. The past two years have seen a decline in profits. Time was when he would sell far greater volumes over a much shorter period. Back then, 30 bags of boulanger, 30 baskets of tomatoes, 1,000 lbs of okra, 1,000 lbs of carilla, 500 squash, 500 lbs of sweet peppers and 500 lbs of hot peppers would be sold to the retailers in a single night. These days that volume of trading happens over two nights, and in the process you have to reduce your prices and take account of spoilage. The circumstances have compelled Singh to reduce his own purchases from the farmers by half.

Time was, too, when some of his buyers would purchase for export. That particular market has dried up in view of uncertainties associated with airlift out of Guyana.

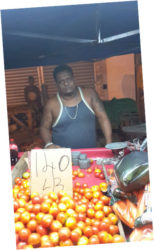

This week, the wholesale price for okra was $30 per lb and a bag of boulanger was being traded for $6,000. These are above average prices. Singh puts it down to “the dry weather.” This week, other wholesale prices were above average too. Sweet peppers were being traded at $160 per lb, hot peppers at $400 per lb, carilla at $80 per lb and tomato at $140 per lb.

The signs of the declining relationship between the vendors and City Hall are manifested in various incremental changes in the circumstances on the ground. Up until relatively recently the vendors were allowed the latitude of unloading their goods ahead of the start 16:30 hrs start of the trading day. Within recent months City Hall has withdrawn that prerogative. These days, the laden canters and cars arrive as early as midday but must wait for the designated start of trading time before they do any unloading. That is not to say that money and goods might not change hands clandestinely long before the unloading of the goods begins.

The whole process is far more complex than it seems. There are fees of $3,000 and $4,500, respectively, for the small and large trucks, respectively, that are pressed into service. The vendors must trade from tables and there is another cost here, $300 per table.

There are rules governing the encumbering the pavements and there is a time limit allowed for unloading the produce. The vendors, it seems, have learnt to comply though there is an underpinning of uneasiness over the arrangement and there may well be more than a hint of truth in the widespread view that the system is not without its flexibilities associated with the payment of considerations.

Trading space has become a challenge in an environment where the demand is high. City Hall says that it is discouraging additions to the existing army of vendors. However, other new vendors are turning up. The newly established Guyana Market Vendors Association (GMVA) has told Stabroek Business that these clandestine additions to the number of traders may well be manifestations of less than above board arrangements involving the municipal constables and the vendors.

Vendors are a hardy breed, used to their independence. Evidence suggests too, that some of them can be wayward, not always particularly mindful of the rules associated with garbage disposal, for example. It is the deterioration in the relationship between them and City Hall that has given rise to the union. The union itself is on an uncertain footing, as yet appearing to lack any real agenda beyond taking the vendors’ side in their spats with City Hall. Whether that limited agenda can sustain the union is unclear. It says it has around 250 members all told. That is not a claim that this newspaper has been able to verify. Singh, however, sees some merit in the creation of a body that can provide some sort of collective representation for the vendors. There is, however, no unanimity amongst them. Some, it seems, prefer to do their own dodging amongst the raindrops, so to speak; living along with what, sometimes can seem like a benign tyranny. Strange as it might seem, that, perhaps, is understandable. Those vendors who have been on the ground long enough have, it seems, resigned themselves to the prevailing regime, the intermittent uneasiness in their relationship with City Hall. They will, occasionally, when things arrive at a point of outrage, raise their voices; but in the end they will return, quickly, to where they were because neither they nor we can afford the loss of the service that they provide. Singh, it seems, begs to differ. He appears to believe that change is possible.