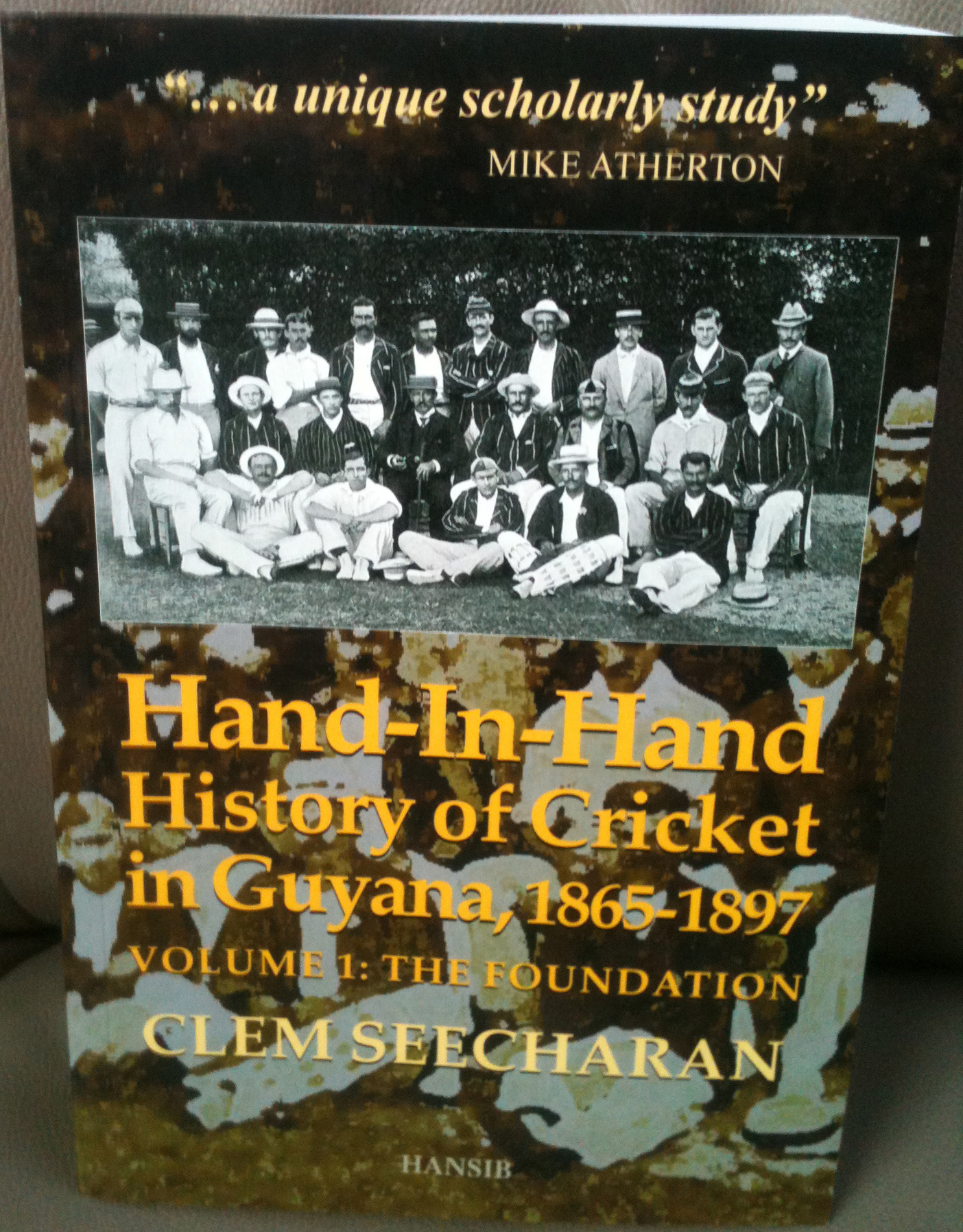

Volume 1: The Foundation (Hansib Publications Limited, 2015) by Clem Seecharran A review by Winston Mc Gowan

This book is the first of a three-volume history of cricket in Guyana from 1865 to 1966. The author, Clem Seecharran, is a professional historian who currently is Emeritus Professor of History at London Metropolitan University in the United Kingdom. The book is a special project of the Hand-in-Hand Fire Insurance Company, Guyana’s first indigenous insurance company, founded in 1865 in the wake of two fires which ravaged a significant part of Georgetown. Its publication, designed to mark the company’s 150th year in Guyana, coincides with the 150th anniversary of first-class cricket in Guyana and the English-speaking Caribbean, where the first such match was contested between Guyana (then British Guiana) and Barbados in Barbados in February 1865.

These circumstances have enabled Professor Seecharran to produce the first detailed account of the early development of cricket in Guyana. The book is particularly welcome because relatively little is known about the history of Guyanese cricket, although cricket has been the most popular spectator sport in the country from at least the 1870s.

The book, however, is not exclusively about cricket on the field of play, that is, within the boundary. It also sheds valuable light on the more general history of Guyana and its people, especially on developments of political and social significance beyond the boundary. In short, the book is, strictly speaking, a social history of Guyanese cricket – a work of the genre of, and drawing inspiration from, the 1963 classic, Beyond a Boundary, of the eminent Trinidadian intellectual, C L R James. Seecharran intertwines his accounts of play on the cricket field especially with issues of race, colour and class, the dominant forces in the wider society, showing the tremendous effect which these factors had on the game. As he states, “a history of cricket in Guyana is an aspect of its social history and crucial to comprehending many issues of social and political significance in the wider history of the only British colony on the mainland of the South American continent.” (p.35)

Readers may be surprised and disappointed that this authoritative work is unable to inform us when and where cricket was first played in Guyana. (p.23). Its author introduces cricket as a powerful sign of the growing Englishness of a territory which was once under Dutch rule, presenting cricket (along with Christianity and western education) as one of the three main pillars of the British cultural mission in the colony. However, relatively little concrete information (as opposed to reasonable speculation) is given about the early development of the game before the formation in 1858 of the Georgetown Cricket Club (GCC), an all-white elite body which is the longest surviving cricket club in the Caribbean. Seecharran indicates that in this early period and for some time afterwards it is not possible to be sure about the quality of play, the background of the players, technical information about the batting and bowling—for example, whether bowlers bowled underhand, round arm or overhand—and many other important aspects of the game. He is on firmer ground from the 1860s when information about cricket gradually became more extensive and less spasmodic in the local newspapers.

Seecharran provides information about the hitherto unknown, earliest recorded matches in Guyana, all –white contests organized by the GCC. He shows that the Parade Ground, opposite the Promenade Gardens, was initially the most important venue for cricket in the colony until it was superseded by the famous Bourda ground which the GCC developed and opened in 1885. By then the originally all-white English game had spread to all the other racial groups in the colony (Blacks, Portuguese, Chinese and Indians) except the Amerindians.

The main or central focus of the book is the GCC. Where domestic cricket is concerned, Seecharran shows that initially and until the 1890s the GCC played matches only against white teams, especially the Garrison club, Queen’s College and visiting British naval and military personnel. He also traces the internal development of the club, including its periodic financial difficulties.

Perhaps even more important than the impetus the GCC gave to development of cricket in the colony was its initiative in promoting regional and foreign competition. Seecharran shows that the GCC was responsible for three major developments. The first was the beginning of competition between Caribbean national teams, starting with two matches between British Guiana and Barbados in 1865. He gives an informative account of all these intercolonial matches until 1897, pointing out that the Guyanese team was composed exclusively of players from the GCC. He shows that the spasmodic initial contests between British Guiana, Barbados and Trinidad, gave way to regular competition after a trophy, the Challenge Cup, was introduced, in 1893, with British Guiana winning it for the first time in 1895. His account also reminds us that in the following year, 1896, British Guiana became the first major Caribbean territory to host Jamaica, hitherto isolated from regional cricket because of its distant geographical position especially in this era of travel by sea.

Seecharran highlights several of the problems of these intercolonial games. Among them were inadequately prepared uncovered pitches with uneven bounce resulting in low individual scores and team totals, the deficiencies in batsmen’s defensive technique, the rarity of boundary hits owing to the grassy condition of the outfield and difficulties faced by wicket-keepers. In these bowler-friendly conditions, the achievement of two Guyanese batsmen in scoring a century–123 by Edward Wright against Trinidad on the Parade Ground in 1882 and 135 by Clement King against Trinidad at Bourda in 1895—was phenomenal. These were the first centuries in first-class cricket in the Caribbean. Seecharran sheds much-needed light on Wright, King and other outstanding early Guyanese cricketers.

The GCC also had two other major initiatives. In 1886 it organised the first tour by a composite West Indies team overseas, to Canada and the United States. It also organised the first West Indies team to play at home, in 1887 against Americans mainly from Philadelphia. Seecharran gives an informative account of these little-known historic tours, including performances by Guyanese members of the regional teams. He also deals with two, hitherto unknown, abortive efforts by the GCC in 1889 and 1893 to initiate and organise a tour by a composite West Indies team to England. Ironically, the book ends with an instructive account of the initial English tours in 1895 and 1897 to the West Indies, including Guyana, noting, however, this development did not owe much to the GCC.

Seecharran emphasises that one important area where the GCC failed to take the lead was in the promotion of multiracial cricket at the national level by the selection of teams on merit irrespective of race, colour and class. The lead in this revolutionary development was taken in 1893 by Trinidad who began to include Blacks in its national team, an example which Barbados and British Guiana were reluctant to follow. The GCC’s obstinate refusal before 1900 to adopt this principle of selection on merit, Seecharran asserts, retarded the club’s cricket and the national game and delayed the emergence of black cricketers in the colony.

This exclusion of non-whites from the membership of the GCC and teams representing Guyana, Seecharran contends, was a major factor responsible for the relatively slow development or progress in the colony’s cricket by 1897. Other principal contributory factors, he argues, were inadequate practice by players, the irregularity of local domestic matches between the GCC and other teams, the infrequency of intercolonial contests and the general lack of high quality competition.

In spite of the obvious value of the book, some readers may have some misgivings. Although the book has several useful illustrations and cartoons, there are few photographs especially of the game and players in the 1860s and 1870s. Photographs from that early era apparently have not survived. The book, however, does include an excellent photograph of Edward Wright, Guyana’s best cricketer in the period under consideration.

A more serious deficiency is that the book, which is preoccupied with the cricket of the dominant GCC, gives very little information about other clubs and the game especially among non-whites, including cricket in the villages and plantations among Blacks and Indians. The focus is on English whites to the virtual neglect of the development of the game among Portuguese, Chinese, Blacks and Indians. There is little attention to all-white matches outside of Georgetown, not involving the GCC. Furthermore, the book is predominantly about cricket in Demerara, mostly Georgetown. The development of the game in Berbice and Essequibo is hardly treated. These deficiencies in relation to these important and still virtually unknown aspects of Guyanese cricket are apparently due largely to the limitations of the sources consulted which were from an era when the press was Georgetown-centred and predominantly white.

These important concerns, however, should not be allowed to detract from the unmistakable fact that Professor Seecharran’s new book makes a monumental contribution to knowledge of Guyanese cricket. It is a scholarly study which many readers will find engrossing. Cricket fans who are interested only or mainly with what transpired on the field of play will be greatly enlightened by the unprecedented amount of information presented about cricket in Guyana, though they may feel that too much attention has been paid to social and political issues beyond the boundary.

It must be remembered, however, that this is a scholarly work which presents a social history of cricket in our country. As the author indicates frequently, “this enigmatic story of cricket cannot be told in isolation from the social history of Guyana. It is, indeed, integral to that history and itself profoundly shaped by it.” (p.150)

Professor Seecharran’s book is the most informative and authoritative work on the early history of Guyanese cricket. Readers will feel deeply indebted to the author and the Hand-in-Hand Fire Insurance Company for this invaluable publication. This reviewer and other readers will eagerly look forward to the other two volumes.